Greenberg Traurig land-use attorney Iris Escarra works on the front line of real estate law in Miami-Dade County, and these days, she’s busy. Very busy. With much of Miami’s prime land already built on, many developers are looking to buy and repurpose lots with vertical projects that combine retail below and offices and residences above, sometimes with a hotel and public transit access, too. That gives Escarra extra work with government agencies to revamp zoning and secure approvals for multiple uses in one building or compound. Greenberg’s footprint across the country and worldwide means Escarra sometimes works with developers, investors or other real estate stakeholders in New York, London and additional far-flung locales, talking by videoconference or welcoming them on visits to Florida.

More complex, pricier projects are among the reasons Greenberg has added real estate lawyers at its Miami headquarters, with its headcount now up to pre-recession levels. More attorneys specializing in the real estate practice may be hired this year, too — not only for work in South Florida but also for the firm’s clients that are active across the United States and beyond, said Escarra, who is co-chair of Greenberg’s Miami land development and zoning practice.

The firm’s client roster features South Florida’s condo giant Related Group, as well as Argentina’s Melo Group, which is currently developing Art Plaza, a two-tower apartment project in Miami’s downtown core. Greenberg is also involved with portions of some of Miami’s megaprojects, completing the zoning and a bond issuance for the $2 billion Miami Worldcenter project and handling due diligence for land purchases and the leasing for the $1.5 billion-plus Brickell City Centre, now in its second phase, Escarra said.

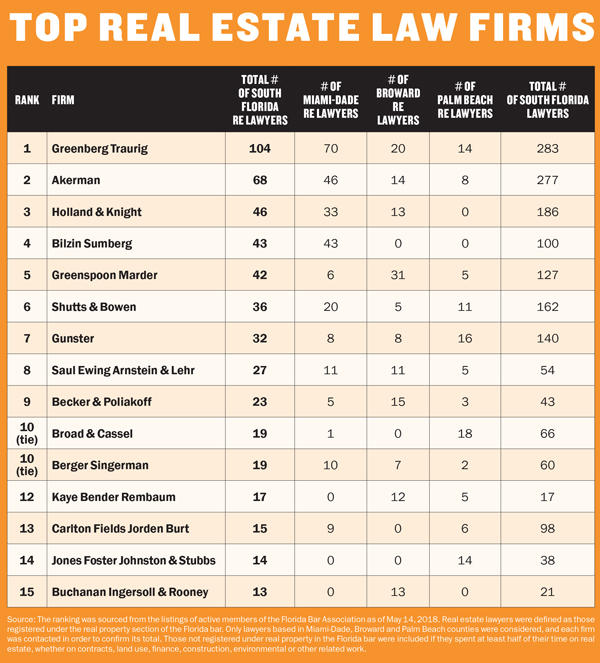

It’s perhaps little wonder then that Greenberg came out on top in The Real Deal’s inaugural ranking of the firms with the largest real estate law practices in South Florida. The ranking was sourced from the listings of active members of the Florida Bar Association as of May 14, 2018. Real estate attorneys were defined as those registered under the real property section of the Florida bar. Only lawyers based in Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties were considered, and each firm was contacted in order to confirm its total. Those not registered under real property in the Florida bar were included if they spent at least half of their time on real estate, whether on contracts, land use, finance, construction, environmental or other related work.

Greenberg — founded in Miami a half-century ago with a focus on real estate — had 104 real estate lawyers and 283 lawyers total in the region as of this ranking. Akerman ranked second, with 68 real estate lawyers in South Florida. Holland & Knight was third, with 46.

How real estate law firms compete in Miami-Dade

To expand their practices, the 15 largest real estate law firms in South Florida use a range of strategies that often leverage their size, whether it’s big or boutique. The larger firms, for instance, tend to emphasize their “soup-to-nuts” offerings, drawing on their vast U.S. and international presence and recommending clients in other offices to their Miami services.

Greenberg’s Miami office now works with real estate investment trusts that buy and sell across the country, said Nancy Lash, co-chair of the firm’s real estate arm in the Miami office.

Smaller law firms, by contrast, tend to highlight their agility as more niche players.

Smaller law firms, by contrast, tend to highlight their agility as more niche players.

Bilzin Sumberg, which, with 43 real estate lawyers, placed fourth in TRD’s ranking, touts an entrepreneurial approach. The firm offers nimble solutions for developers and other risk-takers, said Suzanne Amaducci-Adams, who leads the firm’s real estate and finance practice. “We pride ourselves on problem-solving,” she said. “Entrepreneurs don’t want the perfect 100-page memo. They want an answer.”

Meanwhile, Berger Singerman, which tied for 10th place in the ranking with 19 real estate lawyers in South Florida, finds an edge in partnering with firms outside the state or overseas for handling contracts or other local real estate work. “I get referrals from international firms that have offices in New York, Washington, D.C., California or wherever, who don’t see me as a competitor, because I don’t have an office in their city,” said Jeff Margolis, co-manager of Berger Singerman’s business, finance and tax team.

The right pricing can also make smaller law firms competitive against the Goliaths in the game. Consider the moves by South Florida’s Weiss Serota Helfman (the firm did not make the top 15 cut for top real estate law firms). Long known for its work as counsel for municipalities, Weiss Serota has been expanding into private business, doubling its headcount of real estate lawyers to more than a dozen in the past year. And it offers hourly rates that can best the biggest firms.

“Since the recession and even before, there’s been tremendous pressure from clients on legal fees,” Joseph Hernandez, who leads the firm’s real estate practice and previously worked for a global law firm. He said Weiss Serota’s hourly rates are in the $400 to $550 range, versus $600 to $800 at larger firms. “Firms aren’t better because they’re bigger. I look at the value proposition: Which firm can provide the best value?”

Lawyers at larger firms such as Akerman said they increasingly offer “alternative fee” structures by project or components within a project, instead of billing by the hour, in response to pricing pressure from clients.

Growth areas for real estate law

For decades, Miami law firms counted on legal work with condo development as their bread and butter, but that business is cooling now, sources said. What’s hot are more vertical “live-work-play” projects spanning homes, offices, retail and more, often located by transit hubs. Some are private-public partnerships, which require legal work that includes contracts and financial terms for leasing public property.

“Governments have a lot of land in prime locations, so we’re starting to see land-swap deals,” said Bilzin’s Amadduci-Adams. She said Bilzin helped with government contracts and other matters for All Aboard Florida on its $2.5 billion-plus Brightline high-speed train project, which already links Miami and West Palm Beach and will eventually connect Miami to Orlando.

Akerman is among the law firms that focuses on urban re-development since adding a key land-use department a decade ago. Neisen Kasdin, managing partner for the Miami office, is working on revitalization projects in Miami Beach, where he was the mayor from 1997 to 2001. The department is also active in mixed-used projects in Miami’s Wynwood, Design District and Little Haiti neighborhoods, among others. The office is working on portions of the Brickell City Centre, and it represents soccer star David Beckham’s development group, which aims to build a stadium for Miami’s forthcoming professional soccer team, he said.

Akerman is among the law firms that focuses on urban re-development since adding a key land-use department a decade ago. Neisen Kasdin, managing partner for the Miami office, is working on revitalization projects in Miami Beach, where he was the mayor from 1997 to 2001. The department is also active in mixed-used projects in Miami’s Wynwood, Design District and Little Haiti neighborhoods, among others. The office is working on portions of the Brickell City Centre, and it represents soccer star David Beckham’s development group, which aims to build a stadium for Miami’s forthcoming professional soccer team, he said.

“Miami is different than it’s ever been. It’s a mature market,” Kasdin said. He believes Miami has reached such critical mass it will no longer suffer boom-and-bust swings, instead seeing gentler business cycles as different areas of real estate pick up the slack from a slowdown in condos or any one category.

Some lawyers also see opportunities for business as a result of U.S. tax reform under the Trump administration. They expect the reform will prompt more companies in northern states with higher tax rates to move to Florida (see page 10), where there’s no state income tax, and state corporate tax can dip below 5 percent.

“I’ve been getting phone calls from Northeastern companies that are considering moving their operations down here,” said Barry Lapides, co-manager of the business, finance and tax team at Berger Singerman. “I get inquiries every other week,” mostly from the company principals, he said.

Challenging tasks

While business is booming, there are some factors that make the work itself more difficult for South Florida’s real estate lawyers.

“The permitting and approval process in the municipalities and the counties takes so long. It’s basically taking double the amount of time they normally should [compared to the post-recession period],” said Berger Singerman’s Lapides. “Governments haven’t hired enough staff to keep up with demand,” worried that if the market dips, they’ll be stuck with excess, he said. Understaffing makes it hard to move ahead with projects that require zoning changes, delaying construction and other legal work for firms, Lapides said.

What’s more, even with the Dodd-Frank rollback signed into law in May (see page 54), U.S. banks remain cautious about lending after the recession. That means developers have to be more creative with financing, often turning to investors and lenders abroad, lawyers said.

Vivian de las Cuevas-Diaz, deputy leader of Holland & Knight’s real estate department, said her team rarely closes on a local real estate deal with traditional bank funding these days, often working with private equity funds, joint ventures or private-public partnerships instead.

Even the well-heeled developers are careful about how they structure deals, so that buyers or leasees can more readily secure their own funding. After Greenberg helped Hong Kong’s Swire Properties buy downtown land for Brickell City Centre, it structured those holdings so “all the components are separately owned: retail, condo, office, parking and hotel,” said Gary Saul, co-chair of the firm’s Miami real estate practice. That setup gives Swire more flexibility to buy, sell and fund each part of the massive project and ease the financing for all involved, Saul said.

It’s seeing those major projects come to completion that’s most rewarding for some local real estate lawyers.

Greenberg’s Escarra worked to get much of developer Moishe Mana’s nine-acre Wynwood project approved under a new zoning code that Miami launched in 2010. Approvals took nearly three years of work with the government and community, but “the master plans can’t be downzoned for 30 years,” said Escarra with evident satisfaction.