UPDATED, April 1, 12:17 P.M. Two years ago, Natalie Nichols was getting unsolicited cash offers north of $1.7 million to buy her waterfront home in Miami Beach’s Biscayne Point. She stood to make at least $500,000 on any potential deal. However, the Miami Beach resident and real estate investor wasn’t interested in selling the two-story residence, which features four bedrooms, three bathrooms, a pool with a bay view and a boat dock, she told The Real Deal.

“I was renting to people on a short-term basis and collecting between $10,000 to $15,000 a month,” Nichols said. “I had movie stars with their families who preferred the privacy of a single-family home than being in a crowded hotel.”

After paying the monthly mortgage, taxes, insurance and other costs, she would clear $1,000 to $6,000 in profits. But today, Nichols is the one looking for offers on the house at 1531 Stillwater Drive. She’s asking $1.75 million.

Nichols was forced to stop doing business due to the city’s hard-nosed crackdown on short-term rental property owners. According to a Miami Beach map of short-term rental zones, all the areas in the city made up of all single-family homes don’t allow short-term rentals. Short-term rentals are also banned in South Beach’s Flamingo Park Historic District, which has hundreds of apartments and condominiums in addition to single homes.

Turning up the heat

In September, the City Commission enacted new fines of $5,000, $7,500 and $10,000 for home-sharing hosts who fail to submit affidavits attesting that their properties are in zones where short-term rentals are allowed, fail to register their properties with the city and fail to obtain a business tax receipt number that they must display in their online listings.

The new fines are in addition to the initial penalty for getting caught operating an illegal short-term rental in Miami Beach. Three years ago, the City Commission increased that monetary punishment from $1,000 for each violation to $20,000 for just the first offense. If an owner is busted a second, third or fourth time, the fines can jump to $100,000 a pop.

Miami Beach first banned short-term rentals throughout most of the city in 2010 and instituted the $1,000 fine for each violation. Yet the cottage industry remained largely under the radar until the advent of home-sharing applications such as Airbnb and VRBO led to a surge in short-term rentals in Miami Beach. As more owners rented properties to home-sharing guests, complaints about noise and rowdy parties from neighbors led to more code enforcement calls to fine violators. The hotel industry also launched a political campaign pressuring city officials to further regulate home-sharing hosts and the technology companies that enabled their side businesses. Since then, Miami Beach has enacted heftier penalties for violating the law.

As a result, houses and condos in neighborhoods where short-term rentals are banned are getting harder and harder to sell, as investors seeking to make more lucrative profits offered by nightly and weekly rentals focus on areas of the city that allow the practice, Nichols claimed. She added that homes like hers are also losing value.

“Prices aren’t holding up anymore,” Nichols said. “The best offers are coming in $200,000 less than the average offers I was getting in 2015. And it’s because of the city’s ban on short-term rentals.”

Nichols is not alone in her thinking. Other Sunset Islands property owners and brokers who work in Miami Beach believe the city’s actions aimed at punishing short-term rental operators are scaring off investors hoping to cash in on Miami-Dade County’s hottest tourist market by entering the booming cottage industry of home-sharing via applications such as Airbnb

and VRBO.

“It’s happening with the small condos and the homes where people have other homes and can move out for a period of time in order to rent,” said EWM Realty International senior vice president Nelson Gonzalez.

“It’s happening with the small condos and the homes where people have other homes and can move out for a period of time in order to rent,” said EWM Realty International senior vice president Nelson Gonzalez.

Eloy Carmenate, a broker associate with Douglas Elliman, echoed Gonzalez’s sentiment that the ban is influencing sales of properties $5 million and under.

“Lots in Sunset Islands and the Venetian Islands have been impacted,” Carmenate said. “I have seen a devaluation over the last two, three years.”

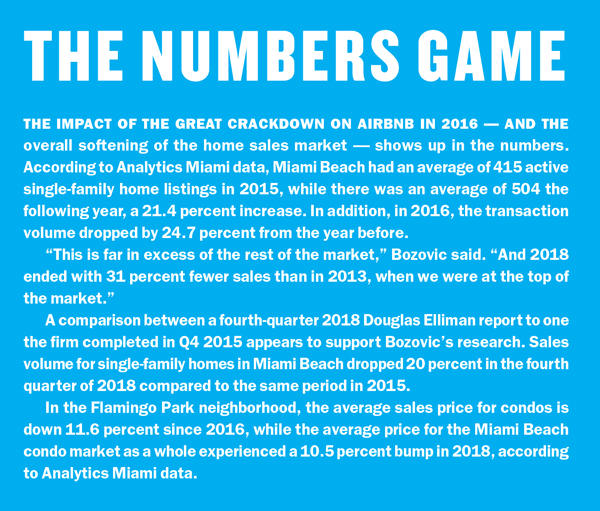

Anecdotal evidence coupled with two years’ worth of downward sales trends in Sunset Islands and other neighborhoods where short-term rentals once flourished further indicate that the ban has been detrimental to the city’s single-family home and condo market under $5 million. Of course, overall Miami Beach sales have been on a downward slide since 2016 due to natural market forces. But experts said the ban is compounding the problem.

Ana Bozovic, a broker who owns real estate data firm Analytics Miami, said areas where short-term rentals proliferated, such as the Flamingo Park Historic District and Sunset Islands, have been adversely affected by Miami Beach’s ban. To support that assertion, Bozovic compared sales volume transactions and the number of listings from 2015 — before the city ramped up enforcement against short-term rentals — and subsequent years.

“The reality is that most of the Miami Beach housing stock is second and third homes,” Bozovic said. “Who wants to buy a vacation home they cannot rent out seasonally?”

The ban is also affecting commercial sales.

“It is clear sales velocity is down,” said Ross Milroy, a Miami Beach-based broker who has been tracking the impact of the short-term rental ban. “I have many clients who own these small buildings. Some own multiple buildings. They cannot sell these buildings for anything that would make them happy to exit their investments.”

Milroy said data from the Multiple Listing Service shows that only 11 Miami Beach apartment buildings sold in the past two years, compared to 46 sold between 2013 and 2015, the peak of the cycle.

Friendlier shores

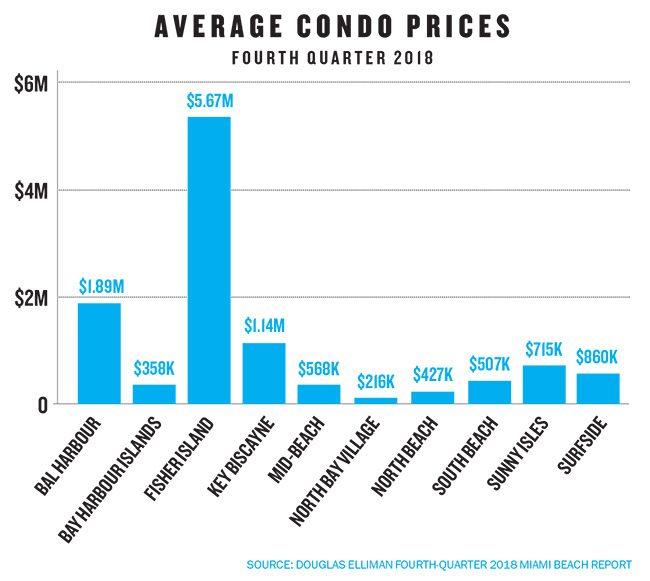

Greg Mermelli, another Sunset Islands property owner who is also suing the city over the ban, said investors are shifting their property searches to North Beach and other coastal cities such as Key Biscayne and Surfside, which don’t fine owners who do short-term rentals.

“All those areas are getting investment money Miami Beach would be getting,” Mermelli said.

Mermelli, whose main business is operating parking sites in Miami and Miami Beach, claims in his lawsuit that the city has cost him at least $7.65 million in lost revenue since the 2010 ban went into effect because he hasn’t been able to legally rent out his waterfront Sunset Islands property on a short-term basis. According to the August 2018 lawsuit, the city fined him $25,000 for violating the ban in April of the same year.

“The city took the wrong approach,” Mermelli said. “They don’t understand that if a Muslim woman or an orthodox Jewish woman wants to go swimming in a pool, they can’t do it at a hotel because they can’t been seen with their bodies uncovered.”

Furthermore, high-profile visitors such as former presidents and celebrities would rather avoid public places such as hotels, where they are going to be mobbed, Mermelli added.

“People are doing short-term rentals all over the place off the books,” he said. “All city officials are doing is shooting themselves in the foot. They are losing tax revenue and diminishing property values at the same time.”

Playing favorites

In their lawsuits, both Mermelli and Nichols claim that city officials have granted exceptions to a few property owners, which has made their homes more valuable than homes that cannot be rented on a short-term basis. Mermelli alleges that Miami Beach has a secret agreement with Christian Jagodzinski, the German multimillionaire owner of luxury rental company Villazzo, which has allowed him to rent out short-term vacation homes since 2002. On its website, Villazzo lists nightly and weekly rentals at waterfront properties in Palm Island, which is a residential zone where short-term leases are not allowed. According to Mermelli’s lawsuit, city records show that Villazzo has not been fined. Via email, Jagodzinski declined to comment.

In her lawsuit, Nichols contends that the city created an elite tier of short-term rental landlords and an unfair playing field by allowing short-term rentals in historic buildings along a stretch of Harding Avenue in the city’s North Beach neighborhood.

“Owners [on Harding Avenue] enjoy a significant advantage over those property owners who are not allowed to conduct short-term rentals,” the lawsuit states. “Not only is property more valuable where short-term rentals are permitted, but North Beach owners also enjoy much less competition under the current scheme, and can accordingly charge higher prices.”

“Owners [on Harding Avenue] enjoy a significant advantage over those property owners who are not allowed to conduct short-term rentals,” the lawsuit states. “Not only is property more valuable where short-term rentals are permitted, but North Beach owners also enjoy much less competition under the current scheme, and can accordingly charge higher prices.”

In motions to dismiss both complaints, Miami Beach attorneys said the lawsuits are a “meritless challenge” and noted that in 2017, 760,000 tourists, or 4.8 percent of the city’s visitors that year, stayed in private homes where the city does allow short-term rentals. Miami Beach also refutes the accusation that some neighborhoods are receiving preferential treatment under the ban. A Miami Beach spokeswoman said the city doesn’t comment on pending litigation.

Problems for pricing

Property values for older apartment buildings in Miami Beach’s historic districts have taken a huge hit amid the crackdown, Milroy said. He noted that many of these buildings, built in the 1950s and 1960s and featuring small bathrooms and kitchenettes, were designed to accommodate tourists

“These properties have not maintained value,” Milroy said. “These properties were built for a vacation experience. They were not built for full-time living.”

Add to the strain the fact that owners of older Miami Beach apartment buildings cannot compete for long-term renters with new apartment buildings in Miami that have been completed in recent years.

“You can go across the bay to downtown and rent a unit in a new building with Class A amenities, including a doorman and security, for less money,” Milroy said. “So for the owner who can’t do short-term rentals, there is no incentive to fix or re-adapt their properties.”

Milroy believes the city’s crackdown will have long-term ramifications on property tax revenues that fund a large part of Miami Beach’s municipal budget. He noted that a majority of the city’s tax base comes from owners of non-homesteaded properties.

“I think things are going to get worse until city commissioners get with the reality that people want to rent vacation homes,” he said. “And a lot of homeowners need to be able to do short-term rentals. The waterfront areas for the uber-wealthy will be okay, but everyone else will get left behind.”

Correction: This article has been amended to reflect that 1531 Stillwater Drive is located in Biscayne Point.