When Noah Breakstone first started shopping for development deals in Orlando in 2008, he didn’t see many others from South Florida doing the same thing.

But within the past few years, Breakstone, CEO and managing partner of Fort Lauderdale-based real estate development and investment firm BTI Partners, said he has seen a gradual increase in the number of South Florida developers turning their eyes northward.

“There’s a good number of developers from Miami up there these days,” Breakstone said. “That wasn’t the case before. It’s very frequent that I’m on the plane with other developers looking at Central Florida.”

If you ask the developers themselves why they are seeking projects in Orlando, they’ll say South Florida’s current development cycle is built out, land is expensive, vacant land is almost nonexistent and other costs are rising. Add to that the fact that Orlando is still growing fast in terms of visitors and population. Some cite the simple need to diversify their portfolio among different markets.

While all of these factors are certainly true, if you dig a little deeper and talk to more experts, you’ll find another reason why rising development costs in South Florida are inspiring developers to invest elsewhere: climate change.

“There’s no question that [rising seas and bigger storms are] driving rising costs along the coast, causing some to pause,” Breakstone said. “There’s only one direction the costs will go, for real estate and for taxes.”

BTI bought an 890-room condo-hotel development, now called the Grove Resort & Water Park, west of Disney World in 2014. For six years, the resort had been vacant and in foreclosure — Central Florida’s largest ever, at $150 million. BTI took possession of it after an auction with a credit bid of $69 million. BTI is still finishing the resort, building out the third phase.

Headline-grabbers who’ve been at the helm of some of South Florida’s biggest projects are also engaged in large-scale developments in Orlando.

Take, for example, Art Falcone — one of the developers behind the $4 billion Miami Worldcenter project — who is now building out a sprawling, Jimmy Buffett-themed Margaritaville development, also near Disney World.

Michael Dezer, too, whose company built the seaside high-rise cluster of Trump Towers and the Porsche Design Tower in Sunny Isles Beach, bought the 104-acre Artegon Marketplace shopping center in Orlando for $23.7 million in January 2018. Dezer is in the process of transforming the mall into a giant auto museum, and has filed plans to build the first of several possible apartment high-rises on the edge of the property.

And then there’s Alex Vadia, the developer behind Miami’s booming Midtown redevelopment, who bought entire city blocks in downtown Orlando in 2016, calling those purchases a long-term investment. Vadia’s buys include about 19 acres where the Orlando Sentinel’s hulking offices are, now emptied of printing presses. Vadia declined to comment on his investment for this story.

Pricey precautions

The cost of climate change and rising seas is very real in South Florida. Many luxury homes on the coast are being built with the idea that the ground floor can flood and leave most of the home above intact. The city of Miami Beach is spending $500 million to raise roads and seawalls. A recent report from Miami-Dade County said a majority of the region’s 67,000 septic tanks could be rendered ineffective in 25 years as water levels rise. The cost to connect all of those septic tanks to sewers would be more than $3.3 billion. As Breakstone said, those items add to taxes, land costs and, eventually, construction costs. Rising insurance costs along the coast also add to overall costs.

Much of Miami is only about six feet above sea level, and Miami Beach has large areas that are lower than that, where high tide events regularly flood streets. Orlando, in contrast, ranges from about 50 feet to more than 100 feet above sea level. The dubiously named Sugarloaf Mountain, just 30 miles west of downtown Orlando, is 312 feet above sea level.

An article published by the science journal Environmental Research Letters in May 2018 found correlations between elevation and property value appreciation in Miami-Dade County.

The article specifically stated that rising seas may result in climate gentrification in Central Florida, and said interviews conducted for the study suggest that “speculative property investors are already hedging on South Florida’s gradual exodus to central and north Florida.”

Despite the reported correlations, the study did not disclose specific cost data as relates to elevation — partly because many other factors influence property values.

“The findings would suggest that a consumer preference may exist in favor of higher elevation properties. Likewise, lower elevation properties may be subject to lower rates of appreciation due to flooding concerns,” the article said.

Jesse Keenan, a social scientist and faculty member at Harvard University and one of the study’s authors, said they did not look at statewide migrations, but the interviews done during their research support the idea that higher-level cities in Florida such as Orlando could be seeing some boost in migration or property value due to sea level concerns.

The allure of Orlando

While Orlando’s commercial and residential prices may one day eclipse those in Miami, they certainly aren’t there yet. Roughly $200,000 can buy a home of about 2,000 square feet in Orlando, but only about 835 square feet in Miami, according to a CNBC story based on 2018 Property Shark data.

There’s also a marked disparity in commercial prices between the two cities. A recent sale of a property in downtown Miami clocked in at $435 per square foot. In comparison, property around the edges of downtown Orlando has sold recently for less than $100 per square foot.

For more developers, Orlando projects seem to offer better bottom lines. Planned and under-construction office projects remain limited in Miami primarily because of high construction costs, high land prices and limited land availability, a CBRE 2019 forecast reported.

The average sales price per square foot for office properties has risen over 76 percent in five years and is projected to continue rising, the report found. In contrast, CBRE’s Orlando report cited “abundance of developable land, coupled with strong demographics.”

Orlando has been ranking in the top 10 U.S. cities for job and population growth in many recent years. The metro area swept past 2.5 million people for the first time in 2017, adding 56,000 residents, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The Miami metroplex, which includes Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach, stood at around 6.1 million in 2017.

Rodrigo Azpurua, president and CEO of Miramar-based Riviera Point Development Group, said Orlando’s growth attracted his company’s investment in two new hotels near SeaWorld. And while the firm hasn’t given up on Miami, he also said he’s seen more Miami-area investors looking at Central Florida.

An additional factor behind Riviera’s Orlando move is to hedge the company’s bets in the event of a major hurricane strike.

“Sea level rise is happening, but not at the level that has impact in short term,” Azpurua said. “Having part of the portfolio in Orlando, in case of a hurricane in South Florida, that will protect us. It’s less likely in Orlando to have a major storm since it’s an hour from the coast.”

Denial ain’t just a river

While plenty of developers will admit that rising costs are driving an increasing number of their projects north, they’re often loath to connect the decision to climate change.

“I’m not smart enough to know what will happen with sea level in the future,” said Scott Webb, president of West Palm Beach-based Kolter Hospitality. “We’ll continue to invest in South Florida. Our moves to other markets are a long-term investment.”

The company is developing an AC Hotel at the top of Orlando’s newest downtown high-rise, the 28-story Church Street Plaza. The 180-key hotel should start on interior buildout this year and open in April or May of 2020, Webb said. Kolter also has new projects in Sarasota and St. Petersburg.

Rising costs are a factor in the company’s search for new markets, said Webb, but construction costs are making it difficult to complete projects everywhere. He dismissed the notion that climate change is behind Kolter’s Orlando investment.

“Like those locations [Sarasota and St. Petersburg], Orlando is attractive to us because it has multiple demand generators in business and leisure travel,” he said. “We look for high-density, urban, walkable locations. There’s only a few markets that offer that in Florida.”

“Like those locations [Sarasota and St. Petersburg], Orlando is attractive to us because it has multiple demand generators in business and leisure travel,” he said. “We look for high-density, urban, walkable locations. There’s only a few markets that offer that in Florida.”

Other developers emphasize an increasing number of benefits to development in Orlando as the primary reason for their moves.

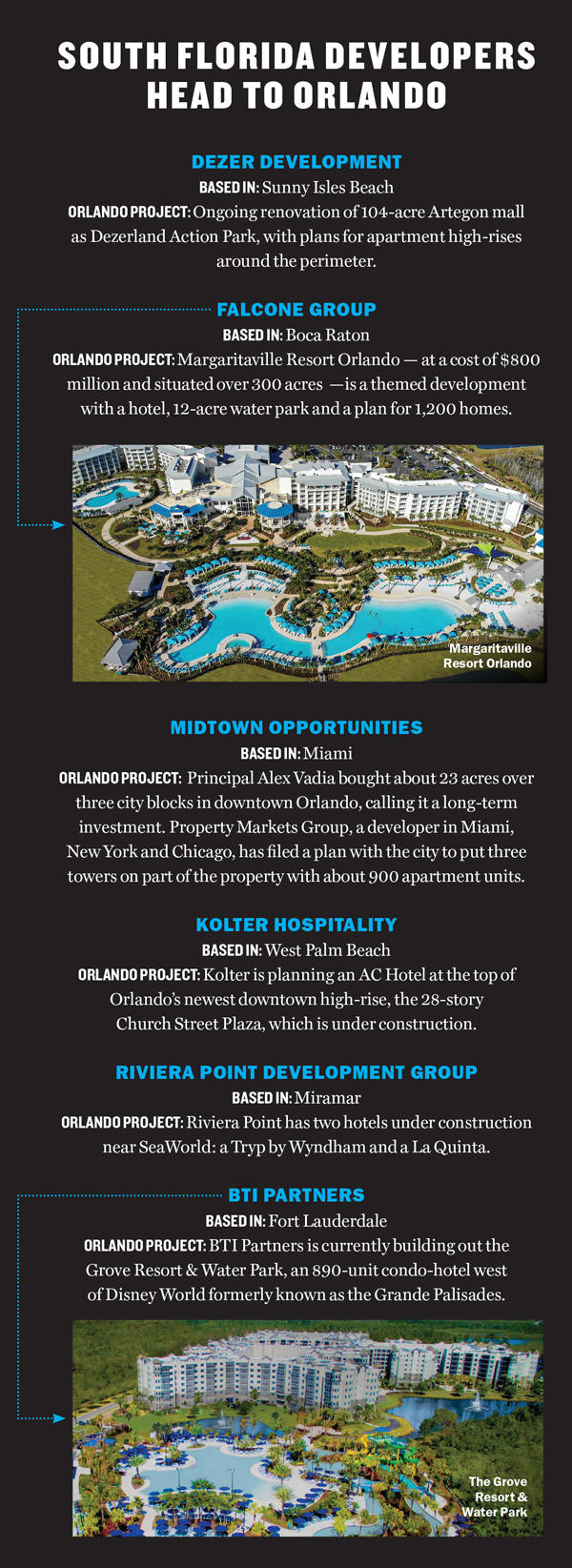

Falcone, for one, is not new to Orlando, but his Boca Raton-based Falcone Group has made big new bets on Central Florida in part due to increased transit options, he said. It’s behind the $800 million, 300-acre Margaritaville Resort Orlando, which opened in December with a 12-acre water park and a plan for 1,200 homes over 300 acres. Vacation homes will start at $250,000. Falcone’s also developed projects in Reunion, a resort community near Disney World.

Falcone said the Miami and Orlando markets are increasingly interconnected. He cited the planned Virgin Trains route that will provide new dedicated rail service between both cities.

“What we’re seeing in Florida over the last 15 years is international travelers will go to Miami and Orlando,” Falcone said. “They take off a couple weeks often, and they want to see both places. That’s why the train connection makes so much sense.”

At 59, Falcone said, he doesn’t see sea level rise as a problem for his Miami Worldcenter.

“I wouldn’t say developers are ignoring it. It’s out of our control except for making buildings more sustainable,” Falcone said. “Downtown, I don’t see that affecting us in my lifetime… maybe the beach areas.”

There’s evidence to suggest that developers and homeowners have the climate issue very much on their minds, said Leonard Berry, retired director of the Florida Center for Environmental Studies at Florida Atlantic University, who has served as a consultant for many environmental development agencies.

“If you’re seeing more South Florida people investing in Central Florida, I’d certainly think they are hedging their bets regarding long-term development,” Berry said.

The conversation is difficult for real estate professionals, added Berry, because they are afraid that more talk about the problem will lead to an exodus from areas along the coast.

Jason King, principal at Miami-based planning and design firm Dover, Kohl and Partners, said most developers still don’t willingly consider sea level rise in their new projects at first.

“They ask why they have to raise to 10 feet when 6 feet is the minimum. We say, ‘You really need to raise to 10 feet,’” King said. Realtors, though, are now talking a lot about rising seas in their conversations with buyers and sellers, he added.

“I bought another house in South Miami last year, and the Realtors talked a lot about sea level rise and climate change. They knew the flood zones and the evacuation zones,” King said.

For many wealthy buyers, however, the appeal of living on or near the water will override any concerns about additional costs, BTI’s Breakstone said.

“The coast is the coast. People who want to be on the water; that’s a big factor for them,” he said.