After leaving his indelible mark in places as varied as Barcelona, Buenos Aires, Frankfurt, India, New York City and Saudi Arabia, England-born architect Brandon Haw is about to do the same in Miami Beach.

Haw, 55, spent 26 years working for Pritzker Architecture Prize-winning firm Foster & Partners before opening his New York firm, Brandon Haw Architecture, in July 2014. He has been intimately involved in the design of two buildings on Miami Beach’s Collins Avenue that are soon to be part of the six-block, ultra-luxurious Faena District. The project is the brainchild of flamboyant Argentinian developer Alan Faena.

In Miami Beach, while still working for Foster & Partners, Haw oversaw the design team creating the Faena House, a residential tower that recently scored a record-breaking $60 million for its penthouse.

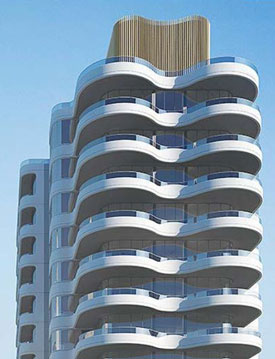

After leaving Foster, Haw remained involved with the Faena District project as the chief architect of a new 16-story, 41-unit condominium building, Faena Versailles Contemporary, whose groundbreaking is expected soon.

I saw a video of you discussing the nature of indoor and outdoor living that is specific to a place like Miami that has good weather. And you mentioned designing “verandas in the sky” as a way to take advantage of the sun and the breeze.

Anybody who’s had a ranch house or a beach house or who’s stayed in one has had the wonderful experience that one enjoys sitting out on the porch or the veranda enjoying the wind and the weather and the sun, and being sheltered from it at the same time. I was spending time with Alan [Faena] in Punta del Este, where he has a wonderful house on the dunes there at San Ignacio. And it came to mind that this sort of idea of living on a beach with these amazing vistas and the skies and the wind and the breezes is a great way to live.

How have you applied that vision to your work on the Faena buildings in Miami Beach … with those specific attributes of places on the coast — the light, the wind, the whiteness?

When we look at Collins Avenue, it is a historic district, so the context of the Faena group of buildings is very important. If you look at Faena House, it is right next door to the Saxony, so it is very much influenced by that postwar, 1948 Moderne horizontality, and yet it is a contemporary piece of architecture.

Move on to the old Versailles Hotel — there you see the classic Art Deco lines … with that symmetry and the way it ripples and undulates. Its sort of stand-alone auto-nomy, as it was originally conceived, was very much an influence on how the new Contemporary Versailles was designed.

So that as [the Contemporary] sits between a 1940 Roy France, then a 2015 Foster & Partners building and then a 1948 Roy France building, it’s a very interesting, harmonious relationship, so that all four buildings work with one another. They’re from different historic periods, with different technologies and different concerns, but all in a historic strip of Collins Avenue,

in a historic district of Miami Beach.

Some people have objected to the fact that the Contemporary will be somewhat taller than the Versailles Classic building next to it.

In cities and in environments, there are rules that have been set, and we’re working within the rules. The fact is that it’s allowed to go 20 feet above.

The principle that it can go a little taller is neither here nor there. I think the rules are there to moderate overdevelopment.

What is the most salient fact people should know about Contemporary Versailles?

It freed up the original Classic Versailles to breathe in its own area. Shifting the new building, the Contemporary Versailles, toward the south … [allowed] the original building to stand alone, and we refurbished the famous corner windows. In so doing, the Contemporary Versailles — very symmetrically based also — takes its cues from the lines of the original historic building, and yet creates this ribbon of undulating lines all the way around, with these very, very large curved terraces that are very aerodynamic.

Because we had the technology of post-tensioned slabs, we can actually get these great curving cantilevers, so the terraces are accessible; they’re large. The lines of the building help mitigate the effects of wind and shade from the sun.

Is it one of your intents to break new ground in design so that it will inspire future architects? Or is that simply a by-product?

As a designer, it’s essential to be true to one’s craft, and to design responsibly and improve and make a difference to people’s lives. If in so doing, the quality of that design effort helps to inspire and helps the debate and makes a difference, adds value, then that’s for others to judge.

You want things that both lift the spirit and — I really believe this — that things have to work well. They have to function.

You were at Norman Foster’s firm for a long time.

Yes. It was the most amazing 26 years, and I’m very thankful for it. But you reach a certain time in life — I just felt it was time to start something new and fresh before it’s too late. We’ve got a great team here in New York, in the Seagram Building. I’m very happy.