Mobile homes are no longer just a necessity for the poor. They’ve increasingly become a must-have for some of the world’s richest private equity players.

A 2016 investor pitch from manufactured housing owner and operator RHP Properties boasted that its portfolio of 33,000 lots — stretching across seven states — had “low cash flow volatility and steady year-over-year rent increases” as well as minimal capital expenditures.

The pitch apparently worked on Brookfield Asset Management, which has poured billions of dollars into trailer park sites in the past few years.

The Canadian private equity giant bought a portfolio of manufactured home sites in 13 states from Colony NorthStar for $2 billion that May. The deal included the acquisition of a joint venture backing RHP’s sites, a Brookfield spokesperson confirmed to The Real Deal.

READ MORE IN THIS SERIES:

Brookfield, which has more than $350 billion in assets, now owns 130-plus mobile home communities, making it one of the one of the largest manufactured housing investors in the U.S. RHP declined to comment for this story.

The immobility of so many mobile and manufactured homes has caught the attention of private equity firms in a big way. With most low-income renters unable to quickly up and move their properties, institutional real estate investors increasingly see that as a surefire bet — especially in a major downturn.

Douglas Danny, a Marcus & Millichap broker who specializes in manufactured housing sites, called them one of the safest assets in a recession. “From 2008 to 2012, there was no effect whatsoever on manufactured housing,” he said. “Now the new buyer coming into the space is the institutional buyer.”

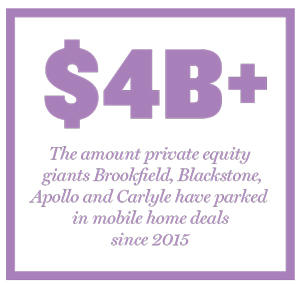

And a who’s who of global investment giants have poured more than $4 billion into the market in the past four years: Brookfield, Blackstone Group, Apollo Global Management and the Carlyle Group have all snapped up, or flipped, trailer parks in that time.

Janet Sallander, a commercial real estate appraiser at Cushman & Wakefield, said mobile homes have become the “default working-class housing.”

“It simply produces better returns compared to other asset classes,” Sallander said.

Mobile home economics

Due to zoning restrictions and the high cost of land in many areas, there are just 6,250 mobile home parks in the U.S., according to a 2019 Cushman & Wakefield report.

Individual plots are rented out to tenants who purchase their own homes. And unlike aging apartment buildings in more heavily regulated housing markets, owners of these lots only need to provide utilities, while residents are responsible for the maintenance and upkeep of their homes.

Blackstone made its first bet on manufactured housing last year when it bought a $172 million portfolio of 5,200 lots from Ontario-based Tricon Capital Group. Other major players — including the Carlyle Group and Sam Zell’s Equity LifeStyle Properties — are snapping up manufactured home communities, with one analyst calling it “the most recession-proof housing stock in existence,” as TRD previously reported.

Blackstone made its first bet on manufactured housing last year when it bought a $172 million portfolio of 5,200 lots from Ontario-based Tricon Capital Group. Other major players — including the Carlyle Group and Sam Zell’s Equity LifeStyle Properties — are snapping up manufactured home communities, with one analyst calling it “the most recession-proof housing stock in existence,” as TRD previously reported.

“A lot of investors are buying big complexes, if they can find them,” said PJ Mikolajewski, president of Ideal Manufactured Homes and a California Manufactured Housing Institute board member. “And as soon as they buy them, they jack the rents up.”

For Alberto Calvillo, a lifelong construction worker who recently moved his family to a site owned by RHP in Bohemia, New York, it was the most affordable option after he was priced out of another mobile home park in nearby Commack.

Calvillo said he now pays $1,000 a month to rent the land where his 900-square-foot house sits. His extended family gathered at the single-wide home, decked out with custom-fitted green and orange panels, on a Sunday afternoon in September.

“This isn’t a mobile home,” Calvillo said with a laugh as he pointed out the obvious lack of wheels, the custom wraparound deck he built and the new concrete foundation. “I’m going to stay here until I die.”

The average cost of moving such a home is $5,000 if the home has wheels to begin with, according to a 2019 report from the national community group MHAction. So when owners of manufactured homes are priced out, they often need to sell their homes at a loss and are replaced by new homeowner-tenants without any big losses for the site’s owner. The result is a low turnover rate and extremely stable revenues.

“If you have the right underwriting, you can increase rent 5 percent each year,” said Marcus & Millichap’s Danny. “Within three to five years, you’ve gone from a 3 or 4 to a 6 [percent] and the park has gone up in value.”

Documents from Florida-based Sunrise Capital Investment — which cite “superior risk-adjusted returns for investors” — give an inside look at the upsides for those in the business.

Manufactured housing is a “recession-resistant” asset class with low turnover that allows for “consistent rent increases,” the pitch to investors reviewed by TRD notes.

“Demand for our product actually increases as the economy tightens.”

Bullish bets

Carlyle, one of the country’s largest private equity firms, made a splash in 2015 when it bought a manufactured home community in Silicon Valley for $152 million.

Tenants in the area soon complained of exorbitant rent hikes and a deterioration in management responsiveness — sparking new calls for statewide rent control in California. The D.C.-based investment group recently flipped the complex, selling it to Chicago-based Hometown America for $237.4 million this August, according to California property records.

Carlyle did not respond to requests for comment.

The rush of private equity into manufactured homes has also attracted the ire of U.S. senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren, who in May wrote stern letters to Brookfield’s Bruce Flatt, Blackstone’s Stephen Schwarzman, Apollo’s Leon Black and Carlyle’s co-CEOs.

“Unable to afford moving, and unable to sell their manufactured homes, some residents report that they are forced to choose between ‘paying for increase[ed] housing costs … or abandoning their homes,’” her letter reads.

One publication called it a Dodd-Frank moment for manufactured home communities, but Blackstone was unfazed. Wayne Berman, the firm’s head of global government affairs, said in his response to Warren that Blackstone hoped to “raise the bar for customer service within an industry that has not always historically provided a high-quality resident experience.”

“Although we’re a tiny part of the overall market, [we’re] dedicated to professional management, capital investment and resident service,” Matthew Anderson, a Blackstone spokesperson, said in a statement to TRD.

Brookfield is “highly attuned” to the fact that the asset class can include lower-income populations, according to the company, which outlined steps the firm has taken to ensure affordability.

In other cases, though, bullish investment strategies have quickly backfired. At one manufactured housing complex in Akron, New York, which Sunrise Capital purchased for under $4 million in 2017, the firm raised rents to $525 from $280 and cut the 122-lot site’s employee payroll by $30,000, sparking an outcry from tenants.

After the residents organized an eight-month rent strike against their new landlord, the complex was placed into a receivership and the investment firm ceded control to the tenants. Representatives for Sunrise Capital declined to comment.

But those bad bets have yet to deter aggressive investors on the whole, industry sources say.

“It could cost [up to] $10,000 to move a home, depending on how big it is,” Rob Ybarra, a debt and equity broker at CBRE based in Las Vegas, noted. “But if you raise rents 25 or 50 bucks — are you going to pick up and go somewhere else? Probably not.

“That’s one of the really big reasons that people like this property type,” Ybarra added. “It’s a captured audience.”