In the summer of 2018, the Eagle Arts Academy was in a crisis. Gregory Blount, former model and events producer who founded the Wellington charter school, was accused of siphoning off $150,000 from the school to his personal companies, leaving the school unable to pay its teachers and attorneys.

The county declared the school unsafe due to understaffing and shut it down just weeks before the new school year began. The school’s landlord, ESJ Capital Partners, was forced to evict the school operator, claiming the school owed it more than $700,000 in unpaid rent, according to the Palm Beach Post.

Unlike other asset classes — such as retail, where the departure of a big box anchor is tough to recover from — charter school properties in South Florida are finding success in landing new tenants and selling quickly.

In December, Miami-based charter school operator Academica struck a deal to lease the 12.4-acre site. The property was never formerly marketed and eventually closed for $14 million in April — a 47 percent increase from what ESJ paid for the site in 2014.

In a similar situation, nonprofit Aspira of Florida found buyers this summer after three of its charter schools shut down, including one in Wynwood that sold for $12.8 million in less than two months after Aspira closed its schools.

Charter schools are increasingly becoming a popular option for investors in South Florida as the supply of available locations narrows, financing becomes more readily available and the demand for non-traditional schools in Florida grows. State lawmakers are backing charter schools as an alternative to public schools, and Governor Ron DeSantis is pushing the schools to take advantage of Opportunity Zone tax breaks by building schools in low-income areas.

In addition, zoning for schools is getting more restrictive, driving up the demand for existing properties, according to industry experts.

“Charter schools are like gas stations — everyone uses them and everyone says that they like them, but no one wants them in their backyard,” said Keith Poliakoff, an attorney at Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr who has worked on a number of charter school deals in South Florida.

“Charter schools are like gas stations — everyone uses them and everyone says that they like them, but no one wants them in their backyard,” said Keith Poliakoff, an attorney at Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr who has worked on a number of charter school deals in South Florida.

Charting growth

Charter schools are a growing phenomenon in American education. They operate as nonprofits and receive state funding, but they have more flexibility around curricula and teaching while also allowing for-profit businesses to get involved.

This year, as Miami-Dade County’s overall student population dropped to 345,368 students from 350,000 last year, charter school population increased to 70,577 from about 68,000, according to the Sun Sentinel.

Florida’s Republican-dominated legislative body and former Governor Rick Scott have championed charter schools over the past few years. In 2017, a law known as “Schools of Hope” was passed in Florida allowing more public funding for charter schools.

Perhaps no local player has been witness to charter school growth as much as Aventura-based real estate investment firm ESJ Capital, which has invested in 41 different school facilities in eight states over the past 10 years.

Matthew Fuller, chief investment officer of ESJ Capital, said it’s become harder to find available sites in South Florida as land has gotten more expensive, zoning has become more difficult and profit margins have diminished. The company is now more commonly finding itself as the interim buyer for schools, purchasing the property, then allowing the school to become stable so it can buy the school and become an owner.

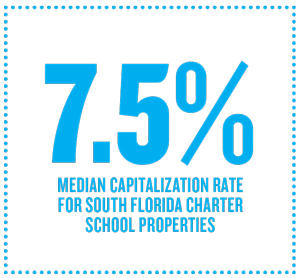

Walter Duke, whose company Walter Duke + Partners has appraised more than 150 charter schools in Florida this cycle, said cap rates for charter schools have decreased. The median cap rates were around 9.2 percent in 2014, but today that number is about 7.5 percent, according to deals that Duke has appraised.

“At this point in the cycle, everything is a little skinnier,” Duke said.

Achikam Yogev of Colliers International South Florida specializes in charter schools and the education sector. He brokered one of the largest charter school portfolio deals in the country when he represented ESJ Capital and MG3 Developer Group in the $107 million portfolio sale of five schools to Portland, Oregon-based Charter School Capital in 2016 and 2017.

Yogev said he is seeing growing demand from new investors because of the consistent returns that charter schools provide.

“Rents are very stable and very fixed and depend on the enrollment in the schools that they have. There is not a lot of guessing,” said Yogev.

But charter schools also have substantial risks: First, it can be hard to reposition the asset into something other than a school. In addition, if the school shuts down before the school year begins, the property owner is left without its main tenant until the next school year. Getting appropriate zoning to build new schools can also be difficult.

But charter schools also have substantial risks: First, it can be hard to reposition the asset into something other than a school. In addition, if the school shuts down before the school year begins, the property owner is left without its main tenant until the next school year. Getting appropriate zoning to build new schools can also be difficult.

“Cities and counties don’t like to downzone land to land that no longer pays taxes, since schools are exempt,” Yogev said.

Jaime Sturgis, the CEO of Native Realty in Fort Lauderdale, is currently marketing the Andrews Charter School at 3500 North Andrews Avenue in Pompano Beach for $5.5 million and expects a cap rate of 6.82 percent for the property. He said that investing in charter schools isn’t as risky as it appears. For one, the schools have state funding. Second, while some schools have run into financial trouble like Eagle Arts, charter schools provide publicly available detailed audited financial statements.

“You can dive in their books and fully understand their in’s and out’s,” Sturgis said.

Poliakoff said that many of the charter schools that have failed are normally those located in shopping centers. He also noted that over the past few years, charter schools have slowly consolidated into a few operators who have specialized in the field.

“A few years ago, everyone and their mother seemed to be applying to be a charter school operator,” said Poliakoff. “As a result, they were left with some very good operators and a lot of operators who have gone under.”

Easy money

A perk of building charter schools is that their developers are able to take advantage of cheaper financing.

As nonprofits, charter schools can tap into tax-exempt municipal bond financing, which is very attractive now that the interest rates are decreasing. This market has grown from $1 billion in 2007 to $3.5 billion in 2017, according to the Local Initiatives Support Corp. It’s also much cheaper than traditional bank financing.

With more indicators signaling that a recession is coming, Duke said that real estate investors see charter schools as a hedge against an economic downturn. Since the schools are dependent upon state funding, they are less vulnerable to the recession or industry disruptions impacting other sectors such as retail.

“Recession or no recession, the kids [have] got to go to school,” Duke said.