In a suburb west of Miami International Airport, far from the glitz and bustle of the urban core, sits a collection of nine brick-red, beige and off-white office buildings from the 1980s.

In October, the Florida Department of Revenue vacated its 41,000-square-foot space at the low-rise campus, called the Office Park at MICC. The debt on the property was soon placed on a watchlist, according to CMBS research firm Morningstar Credit.

The status denotes a more intensive monitoring of the real estate’s financial performance stemming from the vacancy, which represents 10 percent of the office space at MICC, and possible issues with the landlord’s ability to meet obligations on the $38.3 million mortgage balance.

Owner Adler Properties is on time with its payments and not worried about filling the space, as it’s received strong interest from potential tenants, said the firm’s CEO, Jonathan Raiffe.

But he conceded that the MICC is not exactly prime real estate.

“The office park is almost 40 years old and it’s in the Doral submarket,” said Raiffe, adding that Adler pumps in $1 million to $2 million annually for renovations.

The warning on MICC’s debt is an overture to what’s in store for South Florida office real estate.

Although an influx of companies to the tri-county region over the past three years has sheltered it from the vacancies and debt woes common in the U.S., the office market’s swoon will test the limits of South Florida’s resilience, experts say, as tenants abandon suburban offices and high interest rates persist.

Office landlords with loans obtained when rates were historically low will find refinancing expensive. Some have already been socked by skyrocketing insurance premiums, and lenders are skittish about making bets on offices.

“On a global basis, there are going to be properties throughout the country — and South Florida is not immune — where if you have debt maturing next year, there’s a chance you’re going to see some issues and a lot of distress,” said Scott Sherman of Miami-based real estate investment firm Torose Equities.

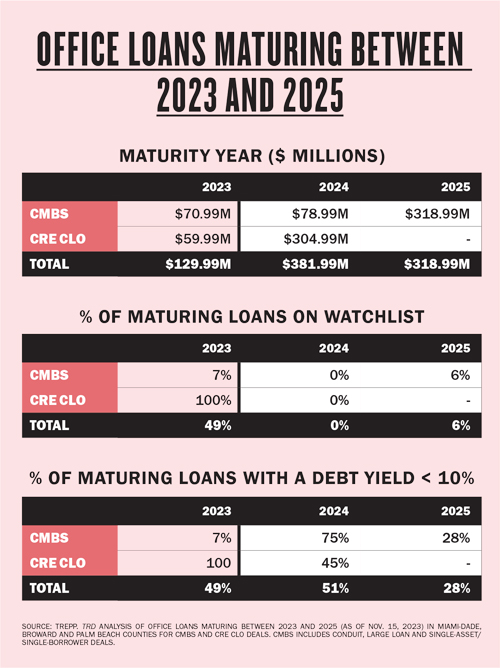

South Florida faces a $130 million wall of maturities for commercial mortgage-backed securities and collateralized loan obligations by year-end, and half of that debt is watchlisted, according to Trepp. Nearly $382 million is set to mature next year, and $319 million in 2025.

“We are in the beginning of this, of offices being put on a watchlist,” said Holly MacDonald-Korth of lender KDM Financial. “We’re just at the beginning of seeing where all of this shakes out.”

Extend and forbear?

The 16-story Alhambra Towers office building in Coral Gables lost law firm Becker and aircraft parts company AerSale last year. The two tenants vacated a combined 43,800 square feet, dropping occupancy almost to 60 percent.

Owner Allen Morris Company’s $61 million loan balance was watchlisted as the debt service coverage ratio dropped to 1, meaning its cash flow was barely enough to cover mortgage payments, according to Morningstar Credit.

But this year, tenants signed deals for the vacant space with rents in the high $50s per square foot, compared to the high $40s for the old leases, said the landlord’s Spencer Morris. The DSCR now is a healthy 2.

“South Florida is not immune. There’s a chance you’re going to see a lot of distress.”

Exactly how bad things will get for South Florida offices over the next two years remains unclear. Although a loan’s watchlisting denotes potential issues, many landlords are able to pull through, as Allen Morris did at Alhambra Towers. In other cases, debt can be watchlisted over small issues, such as an impending maturity date.

CMBS debt comes at fixed interest rates, buffering landlords from rate hikes. CLO debt, however, is floating-rate, potentially leaving owners exposed and in search of rate caps and swaps.

Nearly $60 million in South Florida CLO office debt is maturing this year, all of it collateralized by one property: Alliance HP’s One Financial Plaza in downtown Fort Lauderdale, according to Trepp. The debt has been watchlisted.

Alliance, which didn’t respond to a request for comment, still has a one-year extension option, and “it is entirely possible the loan will get paid off,” said Trepp research director Stephen Buschbom. “But it’s difficult for office owners to refinance right now, because there aren’t as many lenders and the terms are more conservative.”

Debt yield — a property’s net operating income divided by its debt load — is another way to gauge the health of a loan. It reveals how fast a lender can recoup its money if it has to foreclose. A 10 percent debt yield is the minimum that lenders typically require to make a loan.

According to Trepp, roughly half of all local CMBS and CLO debt maturing this year and next has a debt yield below that threshold. This could be a signal that property owners might have to bring in cash when it’s time to refinance, according to Buschbom.

While lenders might accept a debt yield of less than 10 percent during boom times, they have moved up their preference to as high as 15 percent because of economic conditions, he said. Often, borrowers cannot exercise loan extension options if the debt yield falls below a specified threshold.

In September, Brookwood Financial Partners’ $325.4 million loan on 26 office properties, including three in South Florida, was put into special servicing, Morningstar Credit data shows, reportedly because it didn’t meet the required debt yield of 11.5 percent.

The loan’s collateral includes the Lakeside Office Center in Plantation, Commercial Place I and II in Oakland Park and the Sabadell United Bank Building in West Palm Beach. Brookwood didn’t respond to a request for comment.

But when debt woes arise, lenders often opt for forbearance rather than move to foreclose, said Thomas Nealon, director of the University of Miami’s master of law program in property development.

“Playing hardball with the borrowers is not always a winning strategy,” said Nealon, a former general counsel for special servicer LNR. Foreclosure, he said, is not “necessarily the quickest, easiest or most effective way to get repaid.”

Old brown buildings

From late 2020 to early 2022, out-of-state companies moving to South Florida flocked to the canyon of skyscrapers in Brickell, the mural-adorned buildings in Wynwood and new projects in downtown West Palm Beach.

The party hasn’t spread to every corner of the region.

“I think where you will see more distress is Class C office buildings or not terribly attractive office buildings,” said Alex Horn, of Miami-based bridge lender BridgeInvest.

Such offices were once “a place to put a body” but are no longer necessary, he said, thanks to remote work. That is evident in South Florida’s suburbs.

This year, tech firm Ultimate Kronos Group left its longtime home at the Weston Corporate Campus, consolidating its offices. Cable & Wireless Communications withdrew from its 25,000-square-foot headquarters at the Landing at MIA campus, west of the airport, with five years left on its lease. This summer, it offered half of the space for sublease.

Where tenants are hesitant about suburban offices, lenders are steering clear.

Middle-market lender KDM stopped marketing itself as an office lender this year, MacDonald-Korth said.

If the right deal were to come up, the Coral Gables-based firm would still look, she said, but she’s got high standards. The firm would want to see small, preferably homegrown tenants who signed their deals after Covid, MacDonald-Korth said. The building would not have to be in the heart of Brickell but couldn’t be more suburban than, say, Coral Gables.

“The older buildings are more challenging. Do you want to work from home or do you want to go into an old brown building?” she said.

Owners of those aging suburban buildings with maturing loans can face a choice between ponying up to refinance — using cash from their own pockets or from investors, if they can find them — or surrendering the properties to lenders.

Others could find opportunity in the upheaval.

Sherman, of Torose, said he is stalking the market for a “good deal” to purchase an office building at a lower basis than in the boom times of South Florida’s past three years.

“Owners are going to have to make tough decisions,” he said. “Do you put in more capital or give the keys in? The farther out and the more loan maturities, that’s what forces these opportunities to the surface.”