Photo illustration of Rodrigo Niño, with Shorewood’s Larry Davis, 84 Williams Street and 331 Park Avenue South (Getty, Google Maps, iStock)

Johanna Trujillo invested $20,000 in what seemed like a sure thing — a piece of Manhattan real estate.

She and her mother bought into a co-working development with meditation rooms and views of Park Avenue South. That was the draw of Prodigy Network: It allowed regular people to make real estate investments that were usually accessible only to the rich and well connected.

Trujillo, 39, who moved to the U.S. from Colombia when she was 19, planned to use the proceeds to send her teenage son to college.

Instead, she has found herself part of an unfortunate club, a network of people all over the world who collectively invested an estimated $690 million in a company that no longer seems to exist.

Prodigy’s charismatic founder and CEO Rodrigo Niño — a Colombian businessman who became a pioneer in the niche world of crowdfunding for real estate developments — died of cancer in May, after the company had been struggling for more than a year. When investors call Prodigy’s New York office these days, no one picks up. Emails are ignored.

In December, Prodigy’s website shut down for more than a week, cutting off investors’ access to their financial records. What little information they get comes through word of mouth, a patchwork of WhatsApp groups, email threads and Google news alerts.

Where has their money gone? Investors say they don’t know. And many, like Trujillo, doubt they’ll see any of it again.

Still, some are not going quietly into the night. In the last 15 months, investors have filed more than a dozen lawsuits against Prodigy, several alleging fraud. It’s shaping up to be the biggest collapse the real estate crowdfunding industry has seen.

Prodigy is not simply another business shattered by the pandemic, or an investment that just didn’t work out. An investigation by The Real Deal shows that a history of misleading marketing, poor corporate governance and questionable investment strategies made the company vulnerable to implosion long before the coronavirus struck.

“I wish I could say it was a surprise,” said Ian Ippolito, an investor and commentator who writes about the real estate crowdfunding industry. “The things they said just never made sense. They never added up.”

With Niño gone, no one wants to lay claim to the messy remnants of his vision. Prodigy’s business partners include New York developer Shorewood Real Estate Group, which has tried to distance itself from Prodigy for the past year.

The things they said never made sense. They never added up — Ian Ippolito, crowdfunding investor and commentator

A lawyer for Shorewood’s CEO, S. Lawrence Davis, told The Real Deal that Shorewood’s involvement with Prodigy was “limited to providing acquisition and development management services and arranging financing,” adding that it “never solicited investors, never communicated with investors, and never made representations to investors.”

This year, Davis signed off on handing over three of Prodigy’s buildings to their respective lenders. Investors who bought stakes in the buildings were not told.

“Prodigy and Shorewood both have totally disappeared and have gone totally silent on thousands of investors from all around the world,” said one investor from Colombia who asked to remain anonymous. “They have absolutely ignored all responsibilities and all communication.”

The pitch

Niño was among the first to start a real estate crowdfunding platform in America.

He had made a name for himself as a luxury real estate broker in Miami before moving to New York to sell condos at Trump Soho. In 2013, the then-44-year-old burst onto the fledgling crowdfunding scene with the energy of a Silicon Valley founder, in stark contrast to the establishment developers who dominated the city.

His audacious approach, underpinned by a TED Talk-ready message about “democratizing” real estate investment, quickly got the company noticed.

“They were running full-page ads in The Economist,” Ippolito said. “They came out very big.”

Niño and Davis had worked together years before on the William Beaver House, a gaudy condo in the Financial District that initially targeted Wall Street bankers with a campaign featuring a grinning beaver holding a martini. Niño was a sales agent at the building; Davis, then a little-known industry player who started out managing properties owned by his family, was on the development team.

The condo project fizzled. Plagued by money problems and litigation, it was eventually bailed out by CIM Group, which listed most of the apartments as rentals.

After Davis came on board as Prodigy’s development partner, around 2013, he and Niño set a plan in motion: They would buy commercial properties, redevelop them using funds raised from investors and operate them as co-working spaces and extended-stay hotels. (WeWork was just three years old at that point, and Niño believed co-working was going to transform the office market.) Prodigy would make money by taking fees on the investments and Shorewood would earn development fees.

An image of Prodigy’s original team in 2014, with Rodrigo Niño and Larry Davis, center (Source: Instagram).

Davis, who had a background in finance, worked with the lenders, while Niño focused on the investment side. Once the buildings were up and running, any profits from renting out rooms or selling co-working memberships would be paid to investors.

To run the hotels, Davis brought in Korman Communities, a family real estate company based in Pennsylvania. The three firms partnered up to buy three buildings that Korman would operate under its luxury hotel brand, AKA. (A spokesperson for Korman said it received standard property-management fees but never recouped its investment in any venture with Prodigy.)

At that time, New York City’s real estate market was on a high after recovering from the financial crisis, and the legalization of crowdfunding for real estate had opened the door for an exciting — though unproven — model.

People from across the globe signed up to invest, learning about Prodigy on the internet or from local real estate brokers hired to sell the idea on the ground. Some investors lived in countries with volatile economies and were looking for a stable place to park their cash. Others were impressed by Niño’s reputation as a successful entrepreneur.

Looking back, several said in interviews that they weren’t clear on the details of what they were signing up for. Prodigy’s jargon-heavy offering materials were printed only in English, and its corporate structure was a complex web of limited liability companies. But Prodigy’s projections were alluring. “This is one of the points that attracted me,” said an investor from Ecuador. “They offered good returns of 13 to 17 percent.”

The warning signs

Many investors got little to nothing back. By 2019, Prodigy’s developments were deep in debt and struggling to meet their revenue projections. The firm had halted all payments to investors.

“I thought, OK, it’s just a bump in the road,” said Miguel Sánchez, an investor from Mexico.

But as things got worse, the company’s correspondence started to dry up.

Desperate to find others in the same boat, Sánchez started searching Facebook. “I really didn’t know what to do,” he said. “There was not a lot of information.”

Read more

Margarita Galán first heard about trouble at Prodigy through WhatsApp. Last spring, a message appeared on her phone with a link to an article about an ex-Prodigy employee suing the company and alleging financial problems. Galán, who since 2017 had been selling Prodigy investments as a contractor in Bogotá, Colombia, was taken aback.

Prodigy assured her that the case was a one-off from a disgruntled employee. But Galán was concerned. Over two years, she said she sold about $500,000 worth of Prodigy’s investments, including about $40,000 of her family’s savings and the $20,000 from Trujillo and her mother. Her last sale was only months before she got the text.

In the early days, Galán had met with Prodigy’s team in New York and toured the properties. She came home impressed. “You feel your money is going to stay safe,” she said. “You really think, ‘OK maybe this is a really good business. Why not?’”

Now, her clients wanted answers. They were frustrated and confused, but she had no information for them. She said she was just as blindsided as they were.

The vision

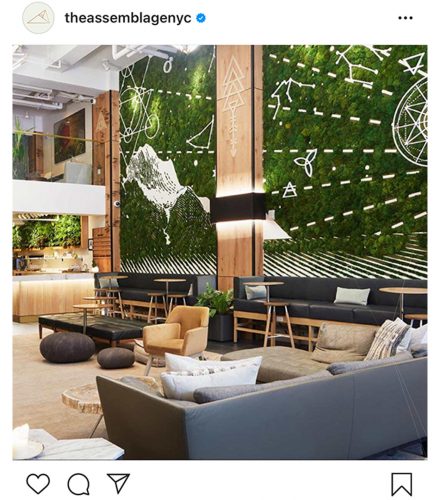

One of Prodigy’s most ambitious plays was creating a co-working brand with a millennial-friendly vibe of consciousness meets capitalism.

“The Assemblage,” with its moss-covered walls, yoga studios and events where members shared ideas about mindfulness and psychedelics, was both a business model and an identity for Niño, who had been transformed by taking ayahuasca in Peru after he was diagnosed with cancer in 2011. (The experience inspired him to get into crowdfunding.)

On Prodigy’s website, the brand’s three Manhattan locations were showcased as glossy investment opportunities alongside three AKA hotels and two Chicago projects, which Korman and Davis were not part of and that have since stalled.

The portfolio gave Prodigy an air of prestige. But behind the scenes, the company’s management was sometimes disorganized, even sloppy, according to sources.

Sánchez, the investor from Mexico, said he became alarmed when confidential financial records belonging to another investor were mistakenly uploaded to his account on Prodigy’s online portal. Another time, he said, Prodigy sent a message to hundreds of investors with their email addresses visible to all.

There were other irregularities. Prodigy had no independent board of directors, something investors might expect from a fund managing hundreds of millions of dollars. And publishing its offering materials strictly in English went against best practice for funds that mainly targeted foreign investors, said Mike Piazza, a Los Angeles-based lawyer at McDermott, Will & Emery, which is not involved with Prodigy.

The tone at the company was largely set by Niño, who had a reputation as a brilliant salesman and a big thinker, but who could be mercurial and controlling, according to a source close to Prodigy. Niño insisted on overseeing every inch of Prodigy’s operations, and without barriers separating the different parts of the business — fundraising, managing investments and running a co-working brand — there were insufficient checks and balances to monitor spending and protect investors’ interests, the source said.

Watching from afar, several investors said they saw Prodigy evolving from a firm focused on investments to one consumed by the Assemblage brand and Niño’s deepening spiritual beliefs.

“I’m not criticizing any ideology, but then when he took a turn for a more spiritual approach … I thought, well, all right, this is going to not go well,” Sánchez said.

The Assemblage became so intertwined with Niño’s identity that in 2017 he organized an unusual deal: Prodigy would buy an upstate New York home from him and turn it into a 143-acre wellness retreat for Assemblage members.

Niño had acquired the property in 2016 for $1.25 million through an entity named Nino Family LLC. To buy it from him, Prodigy raised money through a quick mention in an offering document for an Assemblage building. The note said Prodigy would need no more than $5 million to purchase and redevelop the site. (It did not disclose the link to Niño but mentioned, in general terms, potential conflicts of interest.) Using the money raised, Prodigy bought the home for $1.45 million but abandoned plans for the retreat. Last year, as its plight worsened, it sold the property.

The last time investors heard from Niño was in a video message circulated in April. By that point, he had been receiving treatment for cancer for months; and though he had said in 2019 that he would resign as CEO, he was still running the company.

In the video, Niño was sitting in front of a framed image of a flock of orange butterflies. His face pale, he looked exhausted. He acknowledged that Prodigy was in deep trouble. It was “more than a business failing,” he said, “because I was the business.”

Still, he was adamant that Prodigy could be saved, and said he was still negotiating with lenders. He had few staff left, after laying off dozens the year before. The pandemic had not helped.

There was one final pitch. “If you cannot invest, I really understand,” he said. But, he added, “There is opportunity on the other side of fear.”

He died the next month.

“How did I find out?” the investor from Ecuador said. “I think it was over the Google alerts. … The only things I know about Prodigy are from the news.”

By June, all three Assemblage sites were closed. Though talks had been held with wealthy Mexican investor Moises Kalach about taking over the business, no deal was ever reached. (Kalach and his lawyer did not respond to requests for comment.)

Niño’s widow said in a November court filing that Prodigy had “no active employees beyond one bookkeeper” and planned to file for bankruptcy. She declined to comment for this article.

The avalanche

In September, Katie Burghardt Kramer, a plain-talking litigator at New York firm DGW Kramer, filed four lawsuits against Prodigy, representing investors based in China.

Her cases are among at least 15 now working their way through state and federal courts, as angry investors try to claw back some of their money from the hollowed-out company. Even Prodigy’s accountant has sued, seeking about $275,000 in allegedly unpaid fees.

It’s shaping up to be the biggest collapse the real estate crowdfunding industry has seen.

Prodigy has ignored most of the suits, but not all of them, leaving Burghardt Kramer baffled. “I don’t understand what the logic is,” the lawyer said.” They’ve defended some of the cases. They haven’t appeared in other cases.”

Four other lawsuits, lodged by dozens of investors from various countries, accuse the company of multi-layered deception in its marketing of AKA Wall Street, AKA Tribeca and two Assemblage buildings.

Among the claims the investors make are that Prodigy’s investments were not generating the returns detailed in its offerings and that the company’s management took an undisclosed 16 percent commission from each investment. Cole Schotz, the law firm representing Prodigy’s joint-venture entity in two of these cases, did not return requests for comment.

Another group of investors filed suit over the same two Assemblage buildings, which are among the three properties taken over by lenders this year. The investors argued that by handing over the buildings without warning, Prodigy had violated an agreement it had signed with them — holders of around $250 million in investments — to consult them about any restructuring plans.

The investors’ lawyer claims Shorewood’s Davis was aware of that promise to investors. But Davis signed off on the transfers regardless, according to property records bearing his signature.

The source close to Prodigy claimed there was a “tremendous misalignment of interests” between Davis and the equity holders, noting that Davis was more concerned with the development side of the business. “They were playing a different game,” the source added.

As they look over the wreckage, investors are trying to figure out what rights they have — and whether they can get some money back.

In crowdfunding deals, information about who has the power to do what is usually outlined in offering materials, said Piazza, the L.A.-based lawyer. At a minimum, he said, investors have rights under state law to hold fund managers to their fiduciary duty.

“The question really is, by the time that comes to investors’ attention, is there anything left to fight for?” he said.

The point is not lost on the investors in court. “We’re not holding a tremendous amount of hope at this point,” said Herrick Feinstein lawyer William Fried, who is representing the group of investors, “because what is there to get?”

Investors in crowdfunding deals are generally quite exposed, because managers often have the right to sell investment buildings without getting approval first, said Thomas Kearns, a lawyer with Olshan Frome Wolosky who is not involved with Prodigy. “And if there’s not enough money to pay the investors off,” he added, “too bad.”

In lawsuits and in interviews, some investors claim Prodigy withheld information when it pitched them.

William Boulton, who lives in Venezuela, bought into AKA Wall Street in 2017. The next year, he said, a Prodigy salesperson approached him about reinvesting. Not long after Boulton did so, he said he was told the value of his investment had plummeted.

“All the people that worked at Prodigy should be put in jail,” he said. “They should not be allowed to work in financial services or the financial industry or [any business] related to real estate, ever.”

AKA Wall Street, a target of three legal complaints, closed permanently in August. The windows and doors of the hotel, built at the turn of the 20th century and featuring classical and English baroque architecture, are boarded up with black panels. The building was taken over by Vanbarton Group, one of Prodigy’s lenders, after a UCC foreclosure auction in November.

A recent visit revealed that homeless people had found shelter under the front archway. A makeshift camp was littered with pieces of cardboard, a styrofoam coffee cup and a discarded pair of winter gloves.

The fallout

In interviews with TRD and letters to investors last year, Niño blamed some of Prodigy’s issues on the market, which can scorch even the boldest of ideas. Competition from WeWork and other co-working companies was immense, he said. The Assemblage, which to make any money required a huge number of people to sign up for pricey memberships, simply needed time to grow.

It’s impossible to know whether Niño truly believed The Assemblage could deliver windfalls for investors, but the source close to the company said “there were people around who probably should have known that they were highly unlikely to be able to achieve those results.”

Prodigy’s extended-stay hotels had different issues, Niño said, including competition from Airbnb. But one, AKA United Nations, did pay its investors back. (That was after a large institutional investor was brought into the mix in 2016.) A spokesperson for Korman, the manager of the property, said the firm hopes to re-open AKA United Nations and AKA Tribeca after the pandemic recedes.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission does go after crowdfunding firms over misleading returns, depending on what was offered, said Piazza, who used to work for the SEC and now represents firms under investigation. Most of his clients don’t make specific claims about returns, he said, adding: “They’re very careful about that.”

In his April video, Niño said Prodigy never did anything “inappropriately.” (The SEC declined to comment.) “We may have overbuilt [the buildings] because we wanted to do something spectacular as effectively we did,” he said. “But in reality there was no mismanagement or anything like that at all.”

With Prodigy reduced to one employee, a bookkeeper, it is unclear whom an investigation would even target. “It’s a long time for a company of this size, or a smaller size, for nobody to be there,” said Burghardt Kramer, the lawyer representing Prodigy investors from China. “I would expect that there would have been a fiduciary appointed of some sort, either a bankruptcy trustee or receiver.”

For Prodigy investors living outside the U.S., many of whom don’t speak English, trying to get answers has been a dizzying exercise. How to find American lawyers? How to communicate with them? Pay them?

“I think it’s a huge challenge if you’re an overseas investor to understand how to access the U.S. legal system, to have some faith in the U.S. legal system, even just to figure out what are the right questions to ask,” Burghardt Kramer said.

Many of the investors’ old contacts, the people who might have originally pitched them, are long gone. “I looked them up on LinkedIn, I think, the people that I spoke with before from Prodigy,” Sánchez said. “And none of them worked for Prodigy anymore.”

Galán, the former salesperson in Colombia, has gotten out of real estate altogether. This year, she moved to her hometown, outside Bogotá, to help her aging father with the family automotive business. She said she’s still trying to do what she can for her investors, including Johanna Trujillo and her mother.

“I really feel a responsibility,” she said. “I’m here trying to keep in contact with them, to share information, to try to solve the [situation] in a really good way for all.”

The ground

In June 2019, Trujillo flew to New York with her husband and baby daughter. Her teenage son lives in the city with his father and they had come to watch him graduate from high school.

After the ceremony, they went to Park Avenue South to see the building she and her mother had invested in. It had opened earlier that month, but looking up, Trujillo grew concerned.

“I texted my mom and I said, ‘Mom, the building is closed. I have no idea what’s going on.’”

Later that night, they went back to their hotel, Prodigy’s AKA Wall Street.

“The room we stayed in was nice,” Trujillo said. “It had a view and it was modern.”

Because of her connection to the company, the family had been given two free nights. It is the closest thing to a return on her investment she has ever received.

Jerome Dineen contributed research to this article.

Photo illustration of Rodrigo Niño, with Shorewood’s Larry Davis, 84 Williams Street and 331 Park Avenue South (Getty, Google Maps, iStock)

Johanna Trujillo invested $20,000 in what seemed like a sure thing — a piece of Manhattan real estate.

She and her mother bought into a co-working development with meditation rooms and views of Park Avenue South. That was the draw of Prodigy Network: It allowed regular people to make real estate investments that were usually accessible only to the rich and well connected.

Trujillo, 39, who moved to the U.S. from Colombia when she was 19, planned to use the proceeds to send her teenage son to college.

Instead, she has found herself part of an unfortunate club, a network of people all over the world who collectively invested an estimated $690 million in a company that no longer seems to exist.

Prodigy’s charismatic founder and CEO Rodrigo Niño — a Colombian businessman who became a pioneer in the niche world of crowdfunding for real estate developments — died of cancer in May, after the company had been struggling for more than a year. When investors call Prodigy’s New York office these days, no one picks up. Emails are ignored.

In December, Prodigy’s website shut down for more than a week, cutting off investors’ access to their financial records. What little information they get comes through word of mouth, a patchwork of WhatsApp groups, email threads and Google news alerts.

Where has their money gone? Investors say they don’t know. And many, like Trujillo, doubt they’ll see any of it again.

Still, some are not going quietly into the night. In the last 15 months, investors have filed more than a dozen lawsuits against Prodigy, several alleging fraud. It’s shaping up to be the biggest collapse the real estate crowdfunding industry has seen.

Prodigy is not simply another business shattered by the pandemic, or an investment that just didn’t work out. An investigation by The Real Deal shows that a history of misleading marketing, poor corporate governance and questionable investment strategies made the company vulnerable to implosion long before the coronavirus struck.

“I wish I could say it was a surprise,” said Ian Ippolito, an investor and commentator who writes about the real estate crowdfunding industry. “The things they said just never made sense. They never added up.”

With Niño gone, no one wants to lay claim to the messy remnants of his vision. Prodigy’s business partners include New York developer Shorewood Real Estate Group, which has tried to distance itself from Prodigy for the past year.

The things they said never made sense. They never added up — Ian Ippolito, crowdfunding investor and commentator

A lawyer for Shorewood’s CEO, S. Lawrence Davis, told The Real Deal that Shorewood’s involvement with Prodigy was “limited to providing acquisition and development management services and arranging financing,” adding that it “never solicited investors, never communicated with investors, and never made representations to investors.”

This year, Davis signed off on handing over three of Prodigy’s buildings to their respective lenders. Investors who bought stakes in the buildings were not told.

“Prodigy and Shorewood both have totally disappeared and have gone totally silent on thousands of investors from all around the world,” said one investor from Colombia who asked to remain anonymous. “They have absolutely ignored all responsibilities and all communication.”

The pitch

Niño was among the first to start a real estate crowdfunding platform in America.

He had made a name for himself as a luxury real estate broker in Miami before moving to New York to sell condos at Trump Soho. In 2013, the then-44-year-old burst onto the fledgling crowdfunding scene with the energy of a Silicon Valley founder, in stark contrast to the establishment developers who dominated the city.

His audacious approach, underpinned by a TED Talk-ready message about “democratizing” real estate investment, quickly got the company noticed.

“They were running full-page ads in The Economist,” Ippolito said. “They came out very big.”

Niño and Davis had worked together years before on the William Beaver House, a gaudy condo in the Financial District that initially targeted Wall Street bankers with a campaign featuring a grinning beaver holding a martini. Niño was a sales agent at the building; Davis, then a little-known industry player who started out managing properties owned by his family, was on the development team.

The condo project fizzled. Plagued by money problems and litigation, it was eventually bailed out by CIM Group, which listed most of the apartments as rentals.

After Davis came on board as Prodigy’s development partner, around 2013, he and Niño set a plan in motion: They would buy commercial properties, redevelop them using funds raised from investors and operate them as co-working spaces and extended-stay hotels. (WeWork was just three years old at that point, and Niño believed co-working was going to transform the office market.) Prodigy would make money by taking fees on the investments and Shorewood would earn development fees.

An image of Prodigy’s original team in 2014, with Rodrigo Niño and Larry Davis, center (Source: Instagram).

Davis, who had a background in finance, worked with the lenders, while Niño focused on the investment side. Once the buildings were up and running, any profits from renting out rooms or selling co-working memberships would be paid to investors.

To run the hotels, Davis brought in Korman Communities, a family real estate company based in Pennsylvania. The three firms partnered up to buy three buildings that Korman would operate under its luxury hotel brand, AKA. (A spokesperson for Korman said it received standard property-management fees but never recouped its investment in any venture with Prodigy.)

At that time, New York City’s real estate market was on a high after recovering from the financial crisis, and the legalization of crowdfunding for real estate had opened the door for an exciting — though unproven — model.

People from across the globe signed up to invest, learning about Prodigy on the internet or from local real estate brokers hired to sell the idea on the ground. Some investors lived in countries with volatile economies and were looking for a stable place to park their cash. Others were impressed by Niño’s reputation as a successful entrepreneur.

Looking back, several said in interviews that they weren’t clear on the details of what they were signing up for. Prodigy’s jargon-heavy offering materials were printed only in English, and its corporate structure was a complex web of limited liability companies. But Prodigy’s projections were alluring. “This is one of the points that attracted me,” said an investor from Ecuador. “They offered good returns of 13 to 17 percent.”

The warning signs

Many investors got little to nothing back. By 2019, Prodigy’s developments were deep in debt and struggling to meet their revenue projections. The firm had halted all payments to investors.

“I thought, OK, it’s just a bump in the road,” said Miguel Sánchez, an investor from Mexico.

But as things got worse, the company’s correspondence started to dry up.

Desperate to find others in the same boat, Sánchez started searching Facebook. “I really didn’t know what to do,” he said. “There was not a lot of information.”

Read more

Margarita Galán first heard about trouble at Prodigy through WhatsApp. Last spring, a message appeared on her phone with a link to an article about an ex-Prodigy employee suing the company and alleging financial problems. Galán, who since 2017 had been selling Prodigy investments as a contractor in Bogotá, Colombia, was taken aback.

Prodigy assured her that the case was a one-off from a disgruntled employee. But Galán was concerned. Over two years, she said she sold about $500,000 worth of Prodigy’s investments, including about $40,000 of her family’s savings and the $20,000 from Trujillo and her mother. Her last sale was only months before she got the text.

In the early days, Galán had met with Prodigy’s team in New York and toured the properties. She came home impressed. “You feel your money is going to stay safe,” she said. “You really think, ‘OK maybe this is a really good business. Why not?’”

Now, her clients wanted answers. They were frustrated and confused, but she had no information for them. She said she was just as blindsided as they were.

The vision

One of Prodigy’s most ambitious plays was creating a co-working brand with a millennial-friendly vibe of consciousness meets capitalism.

“The Assemblage,” with its moss-covered walls, yoga studios and events where members shared ideas about mindfulness and psychedelics, was both a business model and an identity for Niño, who had been transformed by taking ayahuasca in Peru after he was diagnosed with cancer in 2011. (The experience inspired him to get into crowdfunding.)

On Prodigy’s website, the brand’s three Manhattan locations were showcased as glossy investment opportunities alongside three AKA hotels and two Chicago projects, which Korman and Davis were not part of and that have since stalled.

The portfolio gave Prodigy an air of prestige. But behind the scenes, the company’s management was sometimes disorganized, even sloppy, according to sources.

Sánchez, the investor from Mexico, said he became alarmed when confidential financial records belonging to another investor were mistakenly uploaded to his account on Prodigy’s online portal. Another time, he said, Prodigy sent a message to hundreds of investors with their email addresses visible to all.

There were other irregularities. Prodigy had no independent board of directors, something investors might expect from a fund managing hundreds of millions of dollars. And publishing its offering materials strictly in English went against best practice for funds that mainly targeted foreign investors, said Mike Piazza, a Los Angeles-based lawyer at McDermott, Will & Emery, which is not involved with Prodigy.

The tone at the company was largely set by Niño, who had a reputation as a brilliant salesman and a big thinker, but who could be mercurial and controlling, according to a source close to Prodigy. Niño insisted on overseeing every inch of Prodigy’s operations, and without barriers separating the different parts of the business — fundraising, managing investments and running a co-working brand — there were insufficient checks and balances to monitor spending and protect investors’ interests, the source said.

Watching from afar, several investors said they saw Prodigy evolving from a firm focused on investments to one consumed by the Assemblage brand and Niño’s deepening spiritual beliefs.

“I’m not criticizing any ideology, but then when he took a turn for a more spiritual approach … I thought, well, all right, this is going to not go well,” Sánchez said.

The Assemblage became so intertwined with Niño’s identity that in 2017 he organized an unusual deal: Prodigy would buy an upstate New York home from him and turn it into a 143-acre wellness retreat for Assemblage members.

Niño had acquired the property in 2016 for $1.25 million through an entity named Nino Family LLC. To buy it from him, Prodigy raised money through a quick mention in an offering document for an Assemblage building. The note said Prodigy would need no more than $5 million to purchase and redevelop the site. (It did not disclose the link to Niño but mentioned, in general terms, potential conflicts of interest.) Using the money raised, Prodigy bought the home for $1.45 million but abandoned plans for the retreat. Last year, as its plight worsened, it sold the property.

The last time investors heard from Niño was in a video message circulated in April. By that point, he had been receiving treatment for cancer for months; and though he had said in 2019 that he would resign as CEO, he was still running the company.

In the video, Niño was sitting in front of a framed image of a flock of orange butterflies. His face pale, he looked exhausted. He acknowledged that Prodigy was in deep trouble. It was “more than a business failing,” he said, “because I was the business.”

Still, he was adamant that Prodigy could be saved, and said he was still negotiating with lenders. He had few staff left, after laying off dozens the year before. The pandemic had not helped.

There was one final pitch. “If you cannot invest, I really understand,” he said. But, he added, “There is opportunity on the other side of fear.”

He died the next month.

“How did I find out?” the investor from Ecuador said. “I think it was over the Google alerts. … The only things I know about Prodigy are from the news.”

By June, all three Assemblage sites were closed. Though talks had been held with wealthy Mexican investor Moises Kalach about taking over the business, no deal was ever reached. (Kalach and his lawyer did not respond to requests for comment.)

Niño’s widow said in a November court filing that Prodigy had “no active employees beyond one bookkeeper” and planned to file for bankruptcy. She declined to comment for this article.

The avalanche

In September, Katie Burghardt Kramer, a plain-talking litigator at New York firm DGW Kramer, filed four lawsuits against Prodigy, representing investors based in China.

Her cases are among at least 15 now working their way through state and federal courts, as angry investors try to claw back some of their money from the hollowed-out company. Even Prodigy’s accountant has sued, seeking about $275,000 in allegedly unpaid fees.

It’s shaping up to be the biggest collapse the real estate crowdfunding industry has seen.

Prodigy has ignored most of the suits, but not all of them, leaving Burghardt Kramer baffled. “I don’t understand what the logic is,” the lawyer said.” They’ve defended some of the cases. They haven’t appeared in other cases.”

Four other lawsuits, lodged by dozens of investors from various countries, accuse the company of multi-layered deception in its marketing of AKA Wall Street, AKA Tribeca and two Assemblage buildings.

Among the claims the investors make are that Prodigy’s investments were not generating the returns detailed in its offerings and that the company’s management took an undisclosed 16 percent commission from each investment. Cole Schotz, the law firm representing Prodigy’s joint-venture entity in two of these cases, did not return requests for comment.

Another group of investors filed suit over the same two Assemblage buildings, which are among the three properties taken over by lenders this year. The investors argued that by handing over the buildings without warning, Prodigy had violated an agreement it had signed with them — holders of around $250 million in investments — to consult them about any restructuring plans.

The investors’ lawyer claims Shorewood’s Davis was aware of that promise to investors. But Davis signed off on the transfers regardless, according to property records bearing his signature.

The source close to Prodigy claimed there was a “tremendous misalignment of interests” between Davis and the equity holders, noting that Davis was more concerned with the development side of the business. “They were playing a different game,” the source added.

As they look over the wreckage, investors are trying to figure out what rights they have — and whether they can get some money back.

In crowdfunding deals, information about who has the power to do what is usually outlined in offering materials, said Piazza, the L.A.-based lawyer. At a minimum, he said, investors have rights under state law to hold fund managers to their fiduciary duty.

“The question really is, by the time that comes to investors’ attention, is there anything left to fight for?” he said.

The point is not lost on the investors in court. “We’re not holding a tremendous amount of hope at this point,” said Herrick Feinstein lawyer William Fried, who is representing the group of investors, “because what is there to get?”

Investors in crowdfunding deals are generally quite exposed, because managers often have the right to sell investment buildings without getting approval first, said Thomas Kearns, a lawyer with Olshan Frome Wolosky who is not involved with Prodigy. “And if there’s not enough money to pay the investors off,” he added, “too bad.”

In lawsuits and in interviews, some investors claim Prodigy withheld information when it pitched them.

William Boulton, who lives in Venezuela, bought into AKA Wall Street in 2017. The next year, he said, a Prodigy salesperson approached him about reinvesting. Not long after Boulton did so, he said he was told the value of his investment had plummeted.

“All the people that worked at Prodigy should be put in jail,” he said. “They should not be allowed to work in financial services or the financial industry or [any business] related to real estate, ever.”

AKA Wall Street, a target of three legal complaints, closed permanently in August. The windows and doors of the hotel, built at the turn of the 20th century and featuring classical and English baroque architecture, are boarded up with black panels. The building was taken over by Vanbarton Group, one of Prodigy’s lenders, after a UCC foreclosure auction in November.

A recent visit revealed that homeless people had found shelter under the front archway. A makeshift camp was littered with pieces of cardboard, a styrofoam coffee cup and a discarded pair of winter gloves.

The fallout

In interviews with TRD and letters to investors last year, Niño blamed some of Prodigy’s issues on the market, which can scorch even the boldest of ideas. Competition from WeWork and other co-working companies was immense, he said. The Assemblage, which to make any money required a huge number of people to sign up for pricey memberships, simply needed time to grow.

It’s impossible to know whether Niño truly believed The Assemblage could deliver windfalls for investors, but the source close to the company said “there were people around who probably should have known that they were highly unlikely to be able to achieve those results.”

Prodigy’s extended-stay hotels had different issues, Niño said, including competition from Airbnb. But one, AKA United Nations, did pay its investors back. (That was after a large institutional investor was brought into the mix in 2016.) A spokesperson for Korman, the manager of the property, said the firm hopes to re-open AKA United Nations and AKA Tribeca after the pandemic recedes.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission does go after crowdfunding firms over misleading returns, depending on what was offered, said Piazza, who used to work for the SEC and now represents firms under investigation. Most of his clients don’t make specific claims about returns, he said, adding: “They’re very careful about that.”

In his April video, Niño said Prodigy never did anything “inappropriately.” (The SEC declined to comment.) “We may have overbuilt [the buildings] because we wanted to do something spectacular as effectively we did,” he said. “But in reality there was no mismanagement or anything like that at all.”

With Prodigy reduced to one employee, a bookkeeper, it is unclear whom an investigation would even target. “It’s a long time for a company of this size, or a smaller size, for nobody to be there,” said Burghardt Kramer, the lawyer representing Prodigy investors from China. “I would expect that there would have been a fiduciary appointed of some sort, either a bankruptcy trustee or receiver.”

For Prodigy investors living outside the U.S., many of whom don’t speak English, trying to get answers has been a dizzying exercise. How to find American lawyers? How to communicate with them? Pay them?

“I think it’s a huge challenge if you’re an overseas investor to understand how to access the U.S. legal system, to have some faith in the U.S. legal system, even just to figure out what are the right questions to ask,” Burghardt Kramer said.

Many of the investors’ old contacts, the people who might have originally pitched them, are long gone. “I looked them up on LinkedIn, I think, the people that I spoke with before from Prodigy,” Sánchez said. “And none of them worked for Prodigy anymore.”

Galán, the former salesperson in Colombia, has gotten out of real estate altogether. This year, she moved to her hometown, outside Bogotá, to help her aging father with the family automotive business. She said she’s still trying to do what she can for her investors, including Johanna Trujillo and her mother.

“I really feel a responsibility,” she said. “I’m here trying to keep in contact with them, to share information, to try to solve the [situation] in a really good way for all.”

The ground

In June 2019, Trujillo flew to New York with her husband and baby daughter. Her teenage son lives in the city with his father and they had come to watch him graduate from high school.

After the ceremony, they went to Park Avenue South to see the building she and her mother had invested in. It had opened earlier that month, but looking up, Trujillo grew concerned.

“I texted my mom and I said, ‘Mom, the building is closed. I have no idea what’s going on.’”

Later that night, they went back to their hotel, Prodigy’s AKA Wall Street.

“The room we stayed in was nice,” Trujillo said. “It had a view and it was modern.”

Because of her connection to the company, the family had been given two free nights. It is the closest thing to a return on her investment she has ever received.

Jerome Dineen contributed research to this article.