A&E Real Estate may have a $500 million problem on its hands.

Back in June 2021, with interest rates at record lows, the multifamily giant refinanced a 31-property portfolio spanning the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Upper Manhattan.

The firm had already sunk nearly $100 million into improvements and slated another $35 million for apartment renovations. It nabbed $506 million in fresh debt from JPMorgan Chase, a three-year loan at a 2.4 percent floating rate. The goal: Finish the work, raise the rents and reap the returns.

The Fed had other plans. Rising rates sent the firm’s debt service coverage ratio plummeting to 0.88. (A figure below 1 means that cash flow is not covering debt payments.) In May, the loan was placed on Morningstar’s watchlist.

Meanwhile, annual rent growth in New York City, which peaked at 29 percent last July, slowed to 10 percent in May, making blockbuster revenue gains for market-rate units a tougher prospect. Most of the portfolio’s units are rent-regulated.

When the loan comes due next June, A&E will be looking at another rate increase if it can’t nab an extension. Another possibility: It won’t be able to refinance at all.

A spokesperson for A&E insisted that the portfolio’s DSCR is above 1, that its net operating income tops Morningstar’s reporting and that it has two extension options — to June 2026.

“The value of our portfolio of well-located, high-quality apartment buildings has only gone up in recent years,” the spokesperson said.

The firm declined to provide a specific ratio or net operating income. Owners cannot always exercise extension options for watchlisted loans.

Whether A&E might save itself from the jaws of default is the same question hundreds of multifamily owners — most of them smaller and with shallower pockets — are currently asking themselves.

Those borrowers, who took out $682 billion in short-term, low-rate loans nationwide in 2021 and 2022, have found themselves sitting on a maturity minefield set to blow during the next two years.

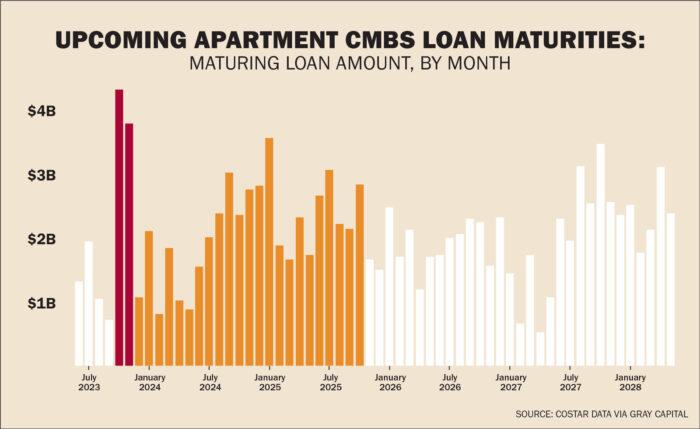

From the third quarter of 2023 through the end of 2025, a record number of CMBS multifamily loans will come due, according to a report from investor Gray Capital.

“This is going to be the Achilles’ heel of the commercial real estate downturn.”

And an analysis by The Real Deal of approaching multifamily maturities reveals the median loan has a DSCR flirting with break-even.

Nearly $8 billion of those loans matures in October and November alone, and experts say the dramatic interest rate gap between late 2021, when much of the debt originated, and the last three months of 2023 will drive a wave of distress.

“I think this is going to be the Achilles’ heel of the commercial real estate downturn,” RXR’s Scott Rechler said last month on TRD’s podcast “Deconstruct.”

“Everyone is focused on office because it’s sexy,” he added. “But all these [multifamily loans] were done in that low- to no-interest-rate paradigm, and so this is where the day of reckoning is coming.”

Typically, rescue capital — preferred equity funded by nonbank lenders — would step in to bridge the gap. But tight debt markets coupled with the sheer volume of maturities mean some assets may not have a way out.

“The big question we still have is: Does the volume of maturities lead to a point where that distress is not contained?” said Gray Capital principal Spencer Gray, who authored the report. “Can rescue capital still come in and save the day?”

Projects in a pinch

Multifamily’s problem loans largely fall into two buckets of short-term debt: construction financing and acquisition bridge loans.

Both tend to carry two- to three-year terms with floating rates. Two years ago, cheap debt and recovering rent growth stoked a surge in multifamily investment that continued through the first half of 2022.

But developers saw projects stymied by Covid delays, then rising rates, leaving a number unfinished. Meanwhile, soft costs — engineering fees, permits, insurance and project management services — kept racking up.

On certain projects, such as the Chetrit Group’s Parkhill City redevelopment in Queens, those delays coupled with rising rates were enough to drive two delinquencies in three months. Since December, the firm has twice fallen behind on a $225 million floating-rate loan covering the two-building multifamily project.

Even after occupancy topped 95 percent this year, net cash flow remained 50 percent below the loan’s underwriting standards, Morningstar data shows. And one building remains unfinished.

As of late June, the loan was marked as current. Chetrit has just one month until the debt matures.

Bridge to nowhere

Bridge borrowers with looming maturities are in a similar bind.

Just as low rates drove record demand for single-family homes, cheap financing spurred a boom in multifamily sales in 2020 into early 2021.

“The difference between a winner of a deal and [a loser] was who can move the quickest,” Gray said. Bridge financing typically offers a speedier closing.

Many of those borrowers were value-add players such as Los Angeles-based Tides Equities, which focused on fix-and-flips across the Sun Belt and banked on rising rents.

“A lot of owners took that opportunity to jump in and do acquisition rehab deals,” said CBRE’s Kyle Draeger. “If you can borrow at 3 percent you’re likely going to do pretty well, as long as your plans work out.”

Many fix-and-flip investors saw their plans unravel over the past two years.

Tides, for one, has $1.5 billion in loans coming due between July and the end of 2025, all floating-rate bridge financing for multifamily buildings across Texas, Arizona and Nevada.

The median interest rate across the portfolio is a low 3.45 percent.

Given the Fed’s promise to increase rates at least twice more by the end of the year, the firm is looking at hefty hikes on at least the 11 loans set to come due between November and February.

Meanwhile, industry insiders say many of those value-add investors haven’t had enough time to realize their rehab strategy and boost income. Portfolio valuations have simultaneously dropped by as much as 20 percent since the beginning of 2022, Draeger said.

Available extensions could serve as a Band-Aid. Two-year loans typically include three one-year extensions, and three-year loans offer two.

But borrowers also need to hit benchmarks to qualify for a longer term. Debt service coverage ratios, for example, must be high enough to satisfy a lender.

In TRD’s analysis of 1,240 floating rate multifamily loans originated between 2021 and 2022 and set to come due between July and the end of 2025, the median DSCR was 1.07. The DSCR at issuance was 1.37.

“A lot of [borrowers] aren’t meeting that debt service coverage test or debt yield test,” Draeger said. “And so then it’s a discussion of: What do you want to do?”

Well-heeled buyers may have the funds to pay down the debt and secure an extension or refinancing.

Matthew Dzbanek, of Ariel Property Advisors, said he has an owner in Brooklyn who agreed to put down an extra $1 million before maturity to rightsize his loan.

Capital calls — asking investors to put up more money — are coming into play.

In a late-June letter to investors, Tides admitted it was facing a crash crunch due to higher interest rates, warning its backers that a capital call was imminent on up to a fifth of its portfolio. Absent more funding, insiders projected Tides may not be able to hold onto its properties.

“We’re not alone in this,” co-founder Ryan Andrade wrote. “There are many other groups out there that bought deals with floating-rate debt over the past 24 months that need capital calls.”

White knights

That leaves rescue funds to fill the gap.

Seth Weissman of private equity firm Urban Standard Capital launched a $100 million fund to aid multifamily owners with loans coming due. Apart from bridge loans, he said, he’s also serviced clients with three- to five-year fixed-rate debt who expect to face distress at maturity.

Some owners who borrowed at 3 or 4 percent interest in 2019, for example, were given more funds than they might qualify for today, Weissman said.

“But the net operating income hasn’t grown sufficiently, if at all, to allow them to service debt at a higher interest rate,” Weissman said, noting that rent-stabilized buildings have been particularly vulnerable.

The firm recently stepped in on a renovated Upper West Side building with $500,000 in net operating income and a $9 million loan. Lenders would only offer a $6 million loan, leaving the borrower to fund the deficit out of pocket.

To ease that commitment, Weissman said Urban Standard might fund an additional $2 million.

“It allows the borrower to buy time, either to a state when rates come down or maybe your leases roll over or you renovate, allowing you to increase revenue,” Weissman said.

“We’re not alone in this. There are many other groups out there that bought deals with floating-rate debt that need capital calls.”

In calls with lenders, Gray said, those who have acknowledged the wall of maturities expect a flurry of sales.

“They say, ‘We’re going to have our sales team involved because the only solution may be to bring it to market,’” Gray said.

Rent-stabilized owners likely have no hopes for a white knight.

“They’re basically completely out of money at this point,” Weissman said. “The values have declined so much in that space that I don’t even know that there is a rescue situation.”

Left behind

Whether rescue capital can keep multifamily afloat may have greater consequences for the banking industry, experts say.

As it stands, Gray said, banks are keeping the multifamily maturity issue “very close to the vest.”

“Basically they’re saying, ‘Hey, there’s gonna be money available and we’re figuring it out,’” he said. “‘Don’t worry about it.’”

That doesn’t mean lenders aren’t worried.

Credit conditions have tightened amid rising rates. And after three high-profile collapses, regional banks that saw an outflow of deposits as clients moved money into bigger institutions have pulled back on lending.

If there are deals that rescue capital can’t or won’t save, those banks may be forced to take back the assets.

A benefit for multifamily is that the fundamentals, unlike with office, remain strong. The housing crisis rages on, and rents have stabilized at higher prices than before the pandemic, meaning rental properties will likely still pull bids.

The risk, though, is that if banks are faced with too many nonperforming assets, the combined effect could put smaller institutions at risk.

“Everyone talks about the wall of refinancing — a big percentage of those are in the top 26 banks and down,” Rechler said, specifying that the top 25 lenders likely won’t face the same flood of maturities.

“We’re not necessarily saying, ‘Absolutely, there’s going to be distress and the market is going to crash,’” Gray said. “But there are these clouds out there that we can see by looking into the past just two years ago.”