In January 2007, in the thick of the commercial real estate mania, when office buildings were the most prized assets in America and banks had a “take my money — please!” approach to credit, Sam Zell sent Steve Roth a “Dear Stevie” email.

Roses are red

Violets are blue

I heard a rumor

Is it true?

Love and kisses,

Sam

The “rumor” in question: Roth, overlord of Vornado Realty Trust, was preparing a counteroffer for Zell’s Equity Office Properties, a 543-building, 103 million-square-foot portfolio that Blackstone Group had agreed to buy for $36 billion, or $48.50 a share. Zell had persuaded Blackstone’s Jon Gray to accept a deal with an unusually small breakup fee — just $200 million — so that other suitors wouldn’t be scared off. And so he reached out to Roth, who replied in kind.

The rumor is true

I do love you

And the price is $52.

To see if this poem will rhyme

We should talk at a set time

While to talk like this is nifty

We should really talk at three fifty.

Forever yours,

Steve

Zell now had what he wanted: a serious third-party buyer, the perfect catalyst for a bidding war. Everyone in the industry knows what happened next: Vornado and Blackstone went toe-to-toe while Zell goaded them along, driving the price of his portfolio even higher. At the end, Blackstone agreed to cough up $39 billion, or $55.50 a share, in what at the time was the largest leveraged buyout in American history.

As consolation, Zell sent Vornado’s leaders and their partner on the bid, Starwood’s Barry Sternlicht, Franck Muller watches inscribed with a pithy aphorism: “Timing is Everything.”

“If you do deals for a living, you know the energy that a big one generates,” Zell later wrote in his memoir. “It’s intoxicating; the air crackles with the energy of anticipation. You are bouncing on your toes all day, every day. It is, quite simply, really fun.”

In the final analysis of Sam Zell, who died in May aged 81, that’s what it comes down to. There are a handful of figures in the real estate pantheon who made more money. Others who left behind a bigger impact on their local skylines, or amassed more political power. But no one — and in all our conversations and accounts of fellow investors, developers and industry leaders, this was unanimous — had more fun.

Last train out

On Aug. 24, 1939, Bernard Zell, a 34-year-old Jewish grain trader from Sosnowiec, a Polish town close to the German border, was heading to Warsaw on business. When his train stopped halfway, he bought a newspaper bearing ominous tidings: Germany and the Soviet Union had just signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, a non-aggression treaty.

To Bernard, who had been closely observing the rise of anti-Semitism in Poland and had been laying the financial groundwork for his exit, the pact meant that his country would become scraps for both superpowers. Time had run out, he realized. He abandoned his business trip and headed home.

On Aug. 31, Bernard, his wife, Rochelle, and their daughter Julie caught a train out of Sosnowiec. The following dawn, the Germans invaded Poland. In his memoir, Zell noted that his family had caught the last train out “before the Nazis bombed the railroad tracks.”

A nearly two-year journey saw the Zells travel through Lithuania, the Soviet Union, and Japan — where the family was among the 6,000 Jewish beneficiaries of visas illegally issued by a Japanese diplomat — before arriving in Seattle in May 1941. Bernard resettled the family in Chicago, where their son, Sam, was born that September.

In his adopted homeland, Bernard gave up the grain trade for the jewelry business, and soon the Zells had the means to move to the prosperous suburb of Highland Park. It was a rough adjustment for an 11-year-old Zell, who described himself as “born to live in the city.” But it also led to his first entrepreneurial venture: smut

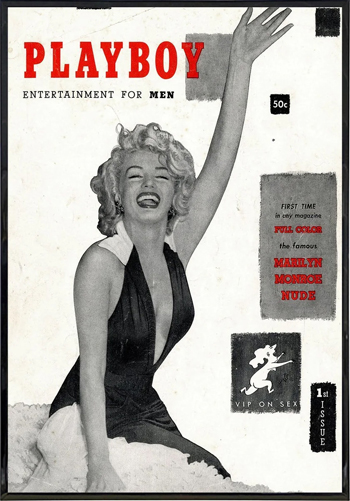

Since Highland Park had little in terms of a Jewish education, Zell’s parents would send him to a yeshiva in Chicago by train, five days a week, and he’d roam the streets after class. On one of those jaunts, he found a newsstand selling a controversial new magazine. Priced at 50 cents, Playboy had America’s most desired woman, Marilyn Monroe, on the cover.

“I brought it home to Highland Park, where it wasn’t for sale, and showed it to my friends,” Zell wrote. He sold it to one of them for $3. “After that, I started a little magazine import business and, in the process, learned a lasting business lesson: Where there is scarcity, price is no object.”

Zell got into the real estate game in college, managing apartments for a landlord. “We got another building and another and another,” he told The Real Deal in 2017. “Eventually, we started buying some, too.” His first building, acquired in Ann Arbor during his second year at law school, cost $19,500. Zell put just $1,500 down, convincing a bank to fund the rest. He was off.

His pitch to reluctant sellers was simple: Student housing was on its way, and they could either “put up with loud music at night and beer cans on the lawn, or they could move to the other side of Ann Arbor. It worked.”

One and done

After graduating from law school, Zell returned to Chicago to try his hand at his new white-collar profession. He lasted about a week.

“In my view, working is all about having a comparative advantage against other people,” Zell said of his legal stint, in which he was asked to negotiate a contract for linens. “I didn’t see my comparative advantage in grunt work.”

He devoted himself to real estate investing and bit off larger properties: a 99-unit rental in Toledo, Ohio, a 160-unit rental in Reno. In 1969, he was introduced to Jay Pritzker, the billionaire scion of the illustrious Chicago family. Pritzker was looking for a sharp young lawyer to come on board and work real estate deals for him. Zell went in and heard the pitch, but he was determined to never have another boss.

“It’s intoxicating; the air crackles with the energy of anticipation. You are bouncing on your toes all day, every day.”

“Jay, I’m not going to work for you or anybody else,” Zell said. “So why don’t we just do a deal together?” That sparked a long partnership, with Pritzker backing Zell on increasingly audacious deals and serving as a mentor on how best to structure them.

Pritzker also funded Zell’s foray into real estate development — Zell thought he would “create the General Motors of the housing industry,” but quickly soured on the whole business after a nightmare experience with a prefabricated project in Lake Tahoe. Regulation, design snags and the prospect that demand and the lending environment could shift during construction made the venture too risky — even for him.

“Most developers must get 50 percent of their returns from real cash flow and the other 50 percent from the intangible benefit of seeing their phallic symbols rise out of the ground,” he later speculated. “Otherwise I can’t see the reward.”

The grave dancer

In the early 1970s, Zell switched from acquisitions to making equity investments in other developers’ projects. But he soon came to the realization that America, primarily because of the availability of cheap capital, was overbuilt.

“This has always been a fatal flaw in U.S. real estate: the volume of development has been related to the availability of funds, not to demand,” he wrote. He shored up his cash and waited for opportunities to come up. He didn’t have to wait too long.

In 1974, the commercial real estate market collapsed. Since at the time, lenders did not have to mark-to-market, they were looking for a player who could step in and come up with a plan that would allow them to wait out the downturn. Enter Zell, who would restructure the debt at a lower interest rate and guarantee that he would feed any deficit, thereby letting the banks avoid taking back the keys.

Lenders flocked to him. In a three-year span, he amassed a $4 billion portfolio “with $1 down and a hope certificate,” as he put it. Around that time, he also gave himself the tongue-in-cheek nickname “the Grave Dancer,” writing in Real Estate Review that “one must be careful while prancing around not to fall into the open pit and join the cadaver. There is often a thin line between the dancer and the danced upon.”

In the 1980s, Zell and his longtime partner, Bob Lurie, diversified into other asset-heavy industries, including manufacturing and agriculture. “Breezy and irreverent, raider Sam Zell runs a $2.5 billion empire,” proclaimed a front-page Wall Street Journal article, which highlighted several traits that would come to define the mogul: opportunism, profanity, an aversion to suits and a love for motorcycles.

In the 1990s, Zell was a pioneer of taking real estate companies public through a REIT structure, which has major tax advantages for investors. He championed the industry in front of regulators, lenders, insurers and politicians. From a sector worth just a few billion dollars, REITs became a trillion-dollar business two decades later.

“I did not invent the modern REIT industry, but I helped make it dance,” he wrote. “The idea that real estate could graduate into the upper class of corporate America was absurd at the time. But by force of will, I knew we could get there.”

It seemed like every decade brought an industry-defining deal. There was the record-breaker with Blackstone in 2007, after which he advised his young counterpart, Gray, to buy a motorcycle.

The media, he explained to Gray, would be all over him after such a headline transaction, and Gray needed to give them a good hook.

“Sam was a legend in every way — a brilliant investor, entrepreneur and business builder,” Gray said in a statement to TRD after Zell’s death. “I loved his uniquely direct style and the example he set on how to live life to the fullest.”

In 2016, Zell sold a 23,000-unit suburban rental portfolio to Sternlicht’s Starwood Capital for $5.4 billion. The following year, he released his memoir, titled “Am I being too subtle?”

Zell’s ascent wasn’t without some major stumbles.

In 1976, he was indicted in a federal tax-shelter investigation, though the charges were later dropped. And in 2007, just months after the Blackstone deal, he made an ill-fated $8.2 billion purchase of the Tribune Company, a major newspaper conglomerate.

His approach to the journalism business — slash costs, consolidate and focus on pageviews over real reporting — made him the poster child for soulless corporate ownership of the media, and he received a barrage of negative press.

“At Sam Zell’s Tribune, Tales of a Bankrupt Culture,” read one story in the New York Times, in which reporter David Carr chronicled a company ridden with debt, starved of editorial resources, and dominated by frat-boy behavior.

Given the press’ sensitivity to its own kind, the deal dominated the perception of Zell in the mainstream media. (The Times, in its May obituary, even went with the headline “Tycoon Whose Big Newspaper Venture Went Bust, Dies.”) Years after the transaction, Zell identified the Tribune purchase as his worst-ever deal. But he was able to maintain some perspective.

“My goal is to be right seven out of 10 times,” he said. “I’m not going to get all hits, but what I’ve gotta do, and what a lot of other people in my field have not done well, is assess the scale of the risk. I start by saying, ‘Can I afford to lose it all?’”

An unusual meeting

In 2001, Chicago developer J. Paul Beitler and Zell were putting together a deal for a new skyscraper at 2 North Riverside, to be anchored by law firm Mayer Brown and accounting giant Deloitte. Zell’s talks with the prospective tenants were to be held in New York City on Sept. 11.

That morning, terrorists struck. The South Tower at the World Trade Center collapsed at 9:58 a.m. Zell kept the meeting.

“We stopped the meeting every 45 minutes or so,” recalled Jay Neveloff, head of Kramer Levin’s real estate practice, who was representing one of the tenants. “There was never a moment where Sam said, ‘wait a second, the world’s ending.’ There was an acceptance by all of us that life would go on, and we’d have to deal with the horror. In a bizarre way, it was therapeutic.”

All flights were grounded, so Zell hopped in a limo to make the 800-mile trip back to Chicago. The proposal for the tower was scrapped in the wake of the attacks, as were dozens of planned skyscrapers nationwide. But both Neveloff and Beitler saw the incident as emblematic of Zell’s approach to the business, and to life.

Zell did too. When it came to dealmaking, there was never a question of stopping.

“Retirement from what?” he replied when asked by TRD in 2017 if he had any plans to do so. “I don’t understand that, because I’ve never worked in my life. I’ve just done stuff that turns me on.”

Sam Lounsberry contributed reporting.