Josh Zegen walks into a glass-walled conference room on the 35th floor of 520 Madison Avenue, blue Polar seltzer in hand. He takes a seat, back to the skyline, his salt-and-pepper beard framing a toothy smile.

Behind him, a crane idles above 660 (formerly 666) Fifth Avenue, a fitting reminder of the endless construction that has made Zegen’s firm, Madison Realty Capital, one of the fastest-growing lenders in the commercial real estate market, with $20 billion in debt and equity deals.

Zegen shares lighthearted anecdotes about his recent bout with Covid. But his affable demeanor belies his sensitivity to his public image — a member of Madison’s marketing team listens in via Zoom while he’s in the room with The Real Deal — and particularly to allegations that Madison has a take-no-prisoners approach to the business. The most recent heat came courtesy of Brooklyn developer Eli Karp, who alleged that Madison’s lending tactics put him out of business — something the firm has denied.

“I’m not looking to fight,” Zegen said. “I’m looking for institutional quality projects, institutional quality borrowers, that really can appreciate the flexibility in what we offer.”

The company, which Zegen runs with Brian Shatz and Adam Tantleff, made its bones as a special-situations lender, bankrolling hairy deals and providing rescue financing for some of New York’s scrappiest builders. In the process, it picked up a reputation for playing hardball, getting ensnared in a series of noisy foreclosure battles. It financed notorious landlord Raphael Toledano’s improbable acquisition of an East Village rent-stabilized portfolio and took control of the properties when Toledano defaulted. It was also a repeat lender to the late “Taxi King,” Gene Freidman and Brooklyn real estate investor Chaim Miller, who was sued by several of his partners and lenders.

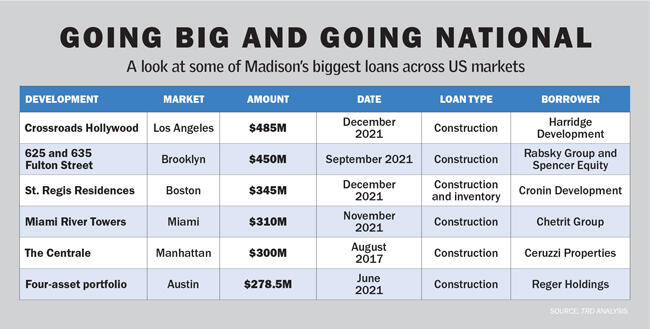

Today, though, the firm’s loan portfolio looks very different, with massive, ground-up construction loans in several major U.S. markets. In December, it cut its biggest construction check ever, a $485 million loan for Harridge Development’s Crossroads Hollywood project in Los Angeles. And at the start of this year, it completed the raise of a $2 billion-plus debt fund, giving it the firepower to go head-to-head with the industry’s most active lenders.

“[Zegen] knows that business in a way that some bank underwriter sitting in a cubicle doesn’t,” said Seth Weissman of Urban Standard Capital, a New York–based private lender and developer.

Even as Madison’s book becomes more institutional, internally it retains its scrappy setup. Zegen is still deeply involved in most major loans and Madison employs only 70 people, far fewer than a traditional private equity firm.

“A lot of these big institutions, the decision-makers are so far away from the deal that it’s just a committee,” said Gary Mozer, co-founder of George Smith Partners, an L.A.-based debt brokerage. “Josh gets his hands dirty. Josh has met my clients. Josh has gone and seen every property.”

Building bridges

Zegen started his career with a stint on Wall Street, working for Merrill Lynch and Salomon Smith Barney. But just as he was being recruited for his dream job in venture capital, the 25-year-old’s rise was snuffed out by the tech bust.

Jobless and living with his parents in Ridgewood, New Jersey, Zegen connected with a friend of his father’s who brokered residential mortgages. After a year or so of arranging loans, Zegen got a taste of his future in 2003: someone was in contract to buy four buildings in Williamsburg on North 6th Street, but his funding fell through. To save the deal, the buyer needed $3 million in a matter of weeks.

Brooklyn real estate finance in those days was a bit of a free-for-all. Professional lenders were rare, and individual investors active in the neighborhood often stepped up to provide gap financing.

While he didn’t have experience in these types of high-stakes and, critically, high-margin deals, Zegen knew those local lenders. He linked the buyer up with one, and in three weeks, the deal was done.

He reached out to Brian Shatz, his former roommate at Brandeis University who was working at BlackRock. The two had run a business of sorts before, selling hats out of their dorm room to fellow students. Zegen pitched Shatz on starting a partnership focused on bridge loans and other special-situation deals.

They could run their shop lean and avoid the decision-by-committee delays their competitors faced. They could also work with borrowers who wouldn’t pass muster with banks. For taking on that increased risk, they’d charge higher rates. But for many borrowers, it’s worth paying a premium for speed.

“People really need you because they’re willing to pay up for things that can be satisfied quickly,” Zegen recalled telling Shatz.

The two were joined by Adam Tantleff, Mark Bahiri, who is now a managing partner at Emerald Creek Capital, and his father, Mike. Shatz and Zegen met Bahiri through Tantleff, who came from boutique asset manager Suffolk Capital Management and had attended elementary school in Westchester with Shatz. Tantleff led fundraising, a role he still holds today. In 2005, they started their first fund with a little over $10 million, with Shatz tapping his high-net-worth connections to find investors.

Hustle was in the firm’s DNA. It hired recent college graduates to cold-call lists of potential backers. Ultimately, Madison pulled in about $300 million from fund of funds and other investors between 2005 and 2008.

Then came the Great Recession. While the implosion of the subprime mortgage market hobbled Wall Street, it was a boon for nonbank lenders. Increased regulation and scrutiny meant banks could no longer provide the kind of real estate loans they used to, opening up opportunities.

With banks and government balance sheets inundated with bad debt, Madison acquired distressed loans while originating mezzanine and construction loans. Free from reserve requirements and other rules, Madison gave loans with more leverage, allowing developers to get projects built with less skin in the game. JLL’s Melissa Rose, who has brokered a few deals with Madison, said she has seen the firm provide financing for up to 85 percent of a project’s total cost.

“Credit committee, originations, underwriting, appraisal-review team, internal counsel — there’s just an immense amount of red tape that a private debt fund is able to cut out,” said Christopher Goetz, a director at New York–based lender G4 Capital Partners. “You go to a debt fund because you need certainty of execution, speed and efficiency, and you need a lender who can structure a deal creatively.”

To ensure a consistent supply of capital, Madison pivoted from an open-end fund to a close-ended fund.

From top: Josh Zegen, Brian Shatz and Adam Tantleff

“We realized we have to create a long-term private equity vehicle,” Zegen said. “People can’t just redeem capital when all of a sudden they have issues elsewhere in their portfolio.”

Hairy scenarios

Madison became comfortable taking on deals that many other lenders shied away from.

It developed a niche backing non-institutional Brooklyn developers. Madison was the go-to lender for Chaim Miller, who at his peak owned over 1 million square feet of real estate across Manhattan and Brooklyn. In 2014, the firm loaned $81 million to a Zelig Weiss–led entity for the posh William Vale hotel in Williamsburg. Three years later, Madison loaned $270 million to Yoel Goldman’s All Year Management for the luxury Denizen apartment complex in Bushwick.

In the Denizen deal, Zegen noted that All Year, whose parent company is now going through Chapter 11 bankruptcy, had a “very, very substantial amount of cash in that deal” so the “loan to cost” was not high.

“I think we always viewed it as real estate first, and we’ll take on the borrower’s execution ability with that risk, and we’ll underwrite that more,” he said.

But Madison’s strategy of targeting special situations could bring it unwanted attention.

In 2015, it provided $124 million in financing to Brookhill Properties, led by 20-something upstart Raphael Toledano, for his rent-stabilized East Village apartment portfolio. Toledano quickly ran into trouble, facing civil lawsuits and allegations of using a fake law firm.

He eventually agreed to pay $3 million in 2019 to settle allegations that he coerced tenants to take buyouts, but recently violated the terms and was banned from New York’s real estate industry for five years. Madison, who now controls the East Village properties, got caught in the crossfire. The New York Attorney General said Madison aided and abetted Toledano’s tenant harassment, and in December 2020 the firm agreed to settle and pay more than $1 million in rent credits to tenants. Madison did not have to admit wrongdoing.

More recently, Madison has battled with Eli Karp of Hello Living.

Between 2018 and 2019, the company bought three separate loans tied to Karp’s Brooklyn projects, including his marquee development, a 210-unit apartment complex in East Flatbush. Madison alleged Karp defaulted on his loan and sought to foreclose on its Flatbush project.

Karp fired back with a civil lawsuit against the lender in June. He alleged predatory tactics by Madison, including that it forced him to sign blank documents and charged a 24 percent interest rate. His allegations are displayed in graphic novel format on a website where Zegen is portrayed as a cartoon villain who uses a vacuum cleaner to suck money out of buildings.

Madison’s lawyers denied the allegations, and a judge dismissed the lawsuit in November. The Flatbush project’s corporate LLC entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

Zegen contends that Madison rightfully bought the loans from other lenders. When Madison makes a loan or buys one, the goal is to be paid off and borrowers have numerous chances to work out a deal. Foreclosure is a last resort, he said.

“Out of $20 billion of loans, 550 transactions or so, you’re going to get a couple of bad apples,” said Zegen.

“If we were really a predatory lender,” he added, “we wouldn’t be here today.”

War chest

Despite its controversies, Madison has attracted a steady stream of borrowers. And crucially, it’s been able to attract big-ticket investors to its funds, including sovereign wealth funds from Asia and the Middle East and the Texas Municipal Retirement System.

“We’d be in a meeting with a pension fund in 2010 and they’d say, “Well, is it my real estate allocation? Is it my credit allocation?” Zegen said. “And you’d have two people sitting there, all pointing at each other, saying, ‘No, you take that on,’ or ‘you take that on.’ It never went anywhere sometimes.”

Madison closed its third fund at $695 million in 2016. Three years later, its fourth fund raised $1.14 billion. The latest one pulled in $2.1 billion and is the second-largest real estate debt fund — only Brookfield’s private debt fund is larger — according to PERE, a publication that tracks private real estate investment activity.

Its new fund comes at a time when investors are hungrier for alternative assets whose yields can beat the weak returns in fixed-income markets. In 2021, real estate debt funds raised $32.5 billion, up from $5 billion in 2010, according to Preqin.

“Everyone is looking for alternative forms of current yield,” said Matt Hershey, a partner at real estate fundraising and advisory firm Hodes Weill & Associates. But even as more capital flows into debt funds, it’s the incumbents that are taking the lion’s share, he added.

“There is going to continue to be a lot of growth,” Hershey said. “But it will be a fairly select group of well established managers doing it.”

More zeros

As Madison’s fundraising has ballooned, so has its deal size.

In December, it loaned $450 million to a Rabsky Group–led joint venture to build a 35-story, 1,100-unit mixed-use property in Downtown Brooklyn.

“If you’re managing billions of dollars, it’s very hard to do that unless you’re writing big checks,” said Weissman of Urban Standard.

And the firm has made a big push outside its home base of New York. In June, Madison loaned $278.5 million to Reger Holdings for a series of multifamily projects and a luxury condominium in downtown Austin. In November, it provided $182.5 million in financing to Scape North America for an apartment project in downtown San Jose, near Google’s new campus.

Neil Shekhter, a major landlord and residential developer on L.A.’s Westside, recently scored a $125 million financing package from Madison for two projects. He said its ability to move fast and do higher-leverage deals meant that he could bypass taking money from outside investors.

“They can get things done that a typical lender cannot,” said Shekhter.

At the height of the pandemic, some Madison competitors such as Bank OZK and Apollo dialed down on their lending in Manhattan, though OZK has since come back roaring. Madison, however, remained active throughout.

“Because folks like Apollo and others weren’t there, developers had no choice but to expand and form new relationships,’’ said Janice Mac Avoy, who co-heads Fried Frank’s real estate litigation practice.

“If you are a middle-market entrepreneurial group, you are not going to break into a lot of the banks,” said David Eyzenberg, head of capital advisory firm Eyzenberg & Company. “That’s where the Madisons of the world come in at a higher cost.”

Madison does not disclose the interest rate on its loans, but a person familiar with the firm’s activities said they generally charge between 6 and 7 percent on senior loans.

“They weren’t the cheapest, but they weren’t the most expensive,” said Bernie Werner, president of Metropica Development, who recently scored a $30 million condo inventory loan from Madison for Metropica’s master-planned community in Sunrise, Florida.

And unlike some lenders, Madison has development chops. They’ve taken on boutique condo projects in Manhattan, and are also building a 700-unit residential complex on the Staten Island waterfront. Zegen says the lending and development sides of the business play off each other: the firm can use its ground-up expertise to gut-check a borrower’s cost estimates, and leverage its understanding of finance to pull in favorable loans for its own projects.

It also means that when things go south for a borrower, Madison can better navigate the responsibilities of an active project. Zegen maintains that taking over a property is always the last option. But at least it is an option.

In August, Madison initiated a foreclosure on Real Estate Equities Corp.’s leasehold interest at 1 St. Mark’s Place in the East Village. Madison alleged Real Estate Equities was in default on a $48 million mortgage.

In January, Madison won court approval to foreclose on a prime plot in the East Village that has laid barren for over two decades. In a statement, the firm defended the move, citing the borrower’s more than three years of nonperformance.

Meanwhile, Madison has built out a new lending outfit to support other alternative lenders, a so-called “loan on loan” vertical. Last year, it originated over $1 billion in financing for 12 alternative lenders across the country.

Since they were selling hats at Brandeis, Zegen and Shatz have stacked deal atop deal. They’ve built out their network and lending capabilities to the point where investors who passed on their first four debt funds have now jumped in for the fifth.

Lending is about money, but that money only comes in if people trust you to make more of it. And everybody from Karp to Rabsky would agree, that’s one thing Madison is good at.

“Everything we do is about the long game,” said Zegen. “It’s about reputation, and it’s about getting that next deal from that borrower.”