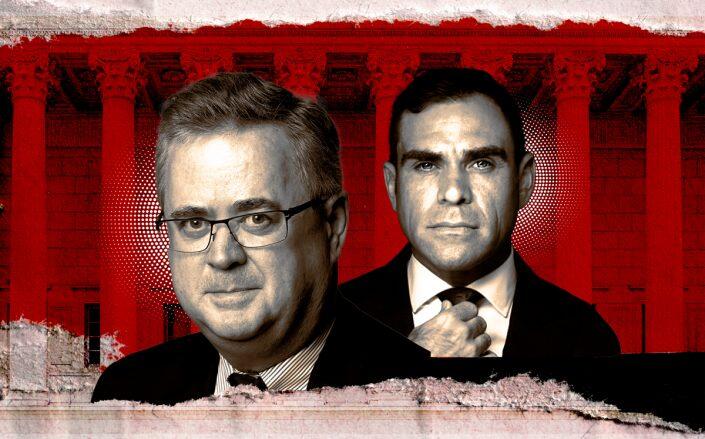

Judge Robert Drain and David Goldwasser (American Bankruptcy Institute, LinkedIn/Illustration by Kevin Rebong for The Real Deal)

When Toby Moskovits stood to lose her trendy Brooklyn hotel to foreclosure last year, she charted a course to the suburbs.

Moskovits’ Heritage Equity Partners was fighting with its lender, Benefit Street, who claimed the Williamsburg Hotel’s $68 million mortgage was in default. Brooklyn-based Heritage turned to David Goldwasser, a fast-talking bankruptcy specialist in Florida who had earned a reputation for exploiting a loophole that allows New York City developers to file for bankruptcy in White Plains.

Big companies in dire straits have been known to lease offices in the quiet city to qualify to restructure there. Historically, they have known which bankruptcy judge they will get, because Westchester County only had one: Robert Drain.

This raised eyebrows last year, when Drain approved the reorganization of OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma, a company blamed for fueling the opioid crisis. Critics said that Purdue and others were “venue shopping” because Drain is thought to favor debtors.

Suspicion that firms game the system is not new. Sen. Elizabeth Warren has sponsored legislation that would limit companies’ ability to pick their court. And late last year, the Southern District of New York — which covers Manhattan, the Bronx and six suburban counties including Westchester — passed a rule to randomly assign judges to major Chapter 11 bankruptcies filed in the district, but it does not apply to entities with less than $100 million in assets or liabilities.

Drain denies that debtors file in Westchester County to get favorable rulings.

“Any assertion that somehow people chose the venue in front of me to get a particular result is just hogwash and offensive and doesn’t stand up,” he said in an interview.

Records show, however, that for years, Brooklyn and Manhattan developers flocked to Drain’s court — with a hand from Goldwasser.

An analysis by The Real Deal found that at least 33 different property LLCs tied to Goldwasser have gone through Westchester County bankruptcy court since 2013. Most of the properties are in Brooklyn or Manhattan, but there’s one as far away as Florida.

Besides the Williamsburg Hotel, Goldwasser has helped put other notable properties into bankruptcy in Westchester, including Cornell Realty’s Tillary Hotel in Downtown Brooklyn; Chaskiel Strulovitch’s 31-building Brooklyn apartment portfolio; and Raphael Toledano’s rent-stabilized East Village apartments. All saw their bankruptcy filings go through Drain.

Any assertion that somehow people chose the venue in front of me to get a particular result is just hogwash.

The Boca Raton-based Goldwasser, 40-something and with a toothy smile, describes himself as an expert in restructuring troubled companies and a man who does everything by the book. He said he has filed many bankruptcies in the Eastern District in Brooklyn and denied that he steered clients to Drain’s court to get a sympathetic ruling.

Yet he is quick to praise Drain’s expertise in handling tricky bankruptcies, calling him “one of the smartest and even-handed judges that most of the people in the country have seen.”

Legal experts, however, have raised concerns about the number of Brooklyn projects that developers have managed to get into his court.

“Why do they want to be in White Plains rather than Brooklyn? That’s the question,” said Adam Levitin, a professor at Georgetown Law specializing in bankruptcy. “What are they getting by having their cases heard by Judge Drain?”

Overruled

The Williamsburg Hotel case heard by Drain has attracted scrutiny. A U.S. trustee — essentially a watchdog of the bankruptcy process — claimed that over $1 million was transferred without appropriate court oversight and that tracking the funds was impossible because the debtor deleted information in its monthly reports.

As a result, the trustee sought to convert the case from a Chapter 11 reorganization to a Chapter 7 liquidation, leaving a court appointed representative to control the assets, or to dismiss the case altogether.

When a company files for bankruptcy, it has to open its books and subject its operations and finances to the approval of a judge. The watchdog’s allegations suggest that the debtor ignored these basic rules.

“The debtor sought protection from its creditors and accepted the benefits of bankruptcy protection,” Greg Zipes, an attorney for the U.S. trustee, wrote in the filing. “The creditors are entitled to the protections afforded by the process as well.”

Goldwasser, however, said the trustee misunderstood the situation. The management company made the transactions, he said, and should be allowed to operate freely because it is separate from the property owner.

Drain ultimately ruled against the trustee. The bankruptcy suit is still pending and the U.S. trustee filed another motion to appoint a Chapter 11 trustee after findings by a court-appointed examiner. Moskovits declined to comment.

“The U.S. trustee has had a very hard time wrapping their arms around the fact that the management company is not in bankruptcy,” Goldwasser said.

Tangled web

Filing for bankruptcy in a distant venue might look strange, experts said, but it’s legal.

Why do they want to be in White Plains rather than Brooklyn? What are they getting by having their cases heard by Judge Drain?

Large corporations and nonprofits do it routinely. The Boy Scouts of America, which is headquartered in Texas, filed for bankruptcy in Delaware by creating an affiliate just months before. Late last year, an HNA Group entity that owns the 245 Park Avenue office skyscraper in Manhattan also filed for bankruptcy in Delaware.

“Bankruptcy venue rules are very, very permissive,” said Levitin, the Georgetown professor.

Goldwasser acknowledges he is sometimes questioned about venues by other parties.

“They are like, ‘Why are properties in Texas filing in Brooklyn?’” said Goldwasser. “When you file in a different physical district than they want you to, they are going to complain.”

In general, a company can file for bankruptcy in its principal place of business, where its principal assets are located, or where it is incorporated, Levitin noted. But it can also file where an affiliated company’s bankruptcy case is pending, he said. A trustee or creditor is allowed to challenge the venue.

It is unclear exactly how Goldwasser got his cases into Westchester, but in his filings he often claimed a case was affiliated with another pending case in the county.

The Williamsburg Hotel bankruptcy wound up in front of Drain after Goldwasser claimed it was affiliated with four other cases in Westchester County involving other properties owned by Moskovits’ firm.

Strulovitch’s Brooklyn bankruptcy likely got to White Plains in 2019 by being attached to another case. Goldwasser put the project through bankruptcy after lender Maverick Real Estate Partners alleged that $40 million in loans it acquired were in default. Kasowitz Benson Torres’ Jennifer Recine, who represented Maverick, declined to comment.

The affiliation in many of these cases was not the developers but Goldwasser himself: He either managed the companies through bankruptcy or had a stake in them.

Toledano’s case, for example, involved a Manhattan landlord, a Manhattan portfolio and a Manhattan lender, Madison Realty Capital. (It did not end well for Toledano: Madison got the East Village properties. Separate from the bankruptcy, Toledano was banned from the industry in New York for five years.)

Long before that, Goldwasser had managed the East Village portfolio. A filing in 2017 claimed that Goldwasser’s firm, GC Realty Advisors, held a 49 percent equity position in the corporate entity, which listed a Manhattan address.

Under New York’s local bankruptcy code, debtors in Manhattan or the Bronx are assigned to a judge in Manhattan. If the debtor is in Rockland County or Westchester County, the clerk should assign the case to Westchester.

There is a caveat, however, that “cases involving debtors that are affiliates shall be assigned to the same judge.”

The Toledano portfolio filing claimed the bankrupt corporate owner was “affiliated” with six other pending cases in Westchester County, all tied to Goldwasser. One dated back to 2014 and involved the bankruptcy of a Jersey Shore shopping center in Manahawkin, 120 miles away, that somehow made it to Drain’s court.

The chain gets even more convoluted.

Goldwasser related the 2014 shopping center case to another one filed in Drain’s court in 2013 where Goldwasser was listed as a manager. That was affiliated with the Goldwasser-managed bankruptcy of a Bronx property in 2012. The Bronx case, in turn, was related to one in Drain’s court in 2011 in which the debtor had an address in Rockland County.

Seven additional entities tied to Goldwasser were related to the Toledano portfolio. In one, the corporate entity of the 174-key Tillary Hotel, owned by Isaac Hager’s Cornell Realty, filed for bankruptcy in 2020, claiming an affiliation with the East Village case. Goldwasser was the restructuring officer.

The filings show Goldwasser could get a case into Drain’s court by loosely relating it to one years before.

For his part, Goldwasser said it makes sense to have numerous cases in one courtroom.

“It might sound funny, but when you have three or four cases in front of the same judge at the same time,” he said, there are “economies of scale of being able to schedule hearings on the same day as status conferences.”

Lenders battling with Goldwasser’s clients occasionally bring up a dark incident from his past: In 2003, he pleaded guilty to one count of criminal bank fraud in Westchester County and was sentenced to 27 months in prison and required to pay $3.3 million in restitution. As a condition of his release, he was, for a time, not allowed to be a fiduciary.

“Concerns of fraud and dishonesty infecting the debtors’ management are heightened by Goldwasser’s involvement,” a lender’s filing in the Strulovitch case asserted.

But Goldwasser said the fiduciary ban applied only when he was on supervised release and ended years ago.

“It’s been brought up because people are uneducated,” said Goldwasser. “Attorneys like to throw stuff. When that comes up in a filing, I say, ‘Great, they have nothing, because this is what they are throwing.’”

Exit plan

Unlike the credentials of some justices who finagle their way onto the state bench through an insider-driven political process, Drain’s are unquestioned.

After graduating from Columbia Law School, he rose to partner in the bankruptcy department at the white-shoe New York law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. In 2002, Drain was appointed to the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York’s court in Lower Manhattan before moving to the White Plains courthouse in 2009.

He has presided over huge, complicated bankruptcies such as that of Sears Holdings Corp. He earned a name as one of the top bankruptcy judges in the country, though his critics say he is partial to debtors — a notion Drain refutes.

“If you look at the results [of] cases that have been filed before me, some have been favorable to the debtor, some have been unfavorable, some have been in between,” he said. “And I hope and trust it’s all because of the merits.”

Levitin called Drain knowledgeable and hard-working, but said filers have concluded that low-level, “drive-through bankruptcies” do not grab his attention.

“These judges aren’t chosen for their expertise,” he wrote in a blog post last year. “Instead, they’re chosen because debtors believe that they will rubber stamp their plans.”

Drain announced last year that he would retire in June, despite a term limit of 2030. “I’m going to be 65 in June,” he explained. “I’ve been on the bench for 20 years.”

Goldwasser said Drain’s departure will not have much impact on his business because he has numerous bankruptcies in other courts and that restructurings often get resolved outside of court.

But that doesn’t mean he won’t miss him.

“Yes, it is sad to see him go,” said Goldwasser. “But everyone has their time.”