Record-low interest rates have created an unprecedented opportunity for homebuyers. That’s the party line in the residential industry. But that’s not how things are playing out on the ground.

Record-low interest rates have created an unprecedented opportunity for homebuyers. That’s the party line in the residential industry. But that’s not how things are playing out on the ground.

Many buyers have little chance to secure the cheap financing that headlines and marketers often claim is fueling the residential market this year.

“If you’re not a wealth management client, most people who want to take advantage of the historically low rates don’t know where to turn,” said Jim Fried, a Miami-based mortgage broker, referring to how banks often reserve favorable loan terms for clients with significant deposits.

“It’s a very difficult process. Extremely difficult. Extremely difficult,” he said. “People don’t realize it.”

Fried’s not alone in talking about the challenges of home financing. But as the national housing market continues its historic climb, many brokers and housing economists are focused on the positive, overlooking the struggles of many buyers trying to qualify for home loans.

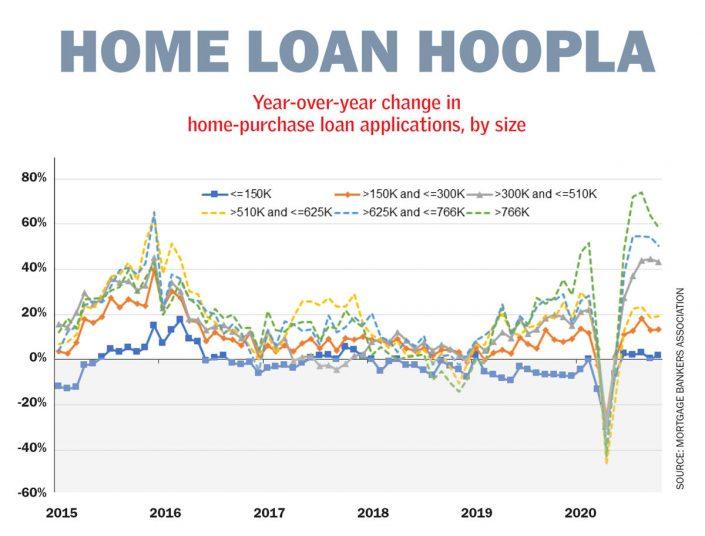

“You’re really just relying on growth in the high end,” said Joel Kan, head of industry forecasting at the Mortgage Bankers Association, noting that mortgage applications for the biggest loans have grown significantly during the pandemic. “Just like any ramp-up, it may run out of steam.”

Though the housing market is continuing its run — with record-high home prices and rising sales — its recovery is uneven. In September, mortgage credit supply, which reflects the accessibility of mortgage financing, hit its lowest level in about six years, according to MBA.

“Lenders are being cautious,” Kan noted. That’s particularly true in major cities, where banks are tightening lending guidelines for jumbo loans — those too large to be sold to government-sponsored entities Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Read more

Though the industry insists some urban markets are invincible, economists are beginning to worry as the pandemic stretches on and some homeowners flee for the suburbs.

“There is a risk that the longer the pandemic goes on, home values may actually drop in those places,” said Daryl Fairweather, Redfin’s chief economist, pointing to Manhattan and San Francisco as examples. “And that is not something a lender wants to be giving a mortgage for.”

Big city bust

JPMorgan Chase is the most high-profile example of betting against New York City.

In early November, the bank limited jumbo home loans in Manhattan to 70 percent of the sales price, down from 80 percent previously, according to a report by Bloomberg. (A few days later, the bank’s head of consumer lending told investors that the bank is still bullish on other housing markets across the country, and was even loosening some lending criteria as home prices rise.)

Jumbo loans dominate major urban markets, where housing is more expensive. The median sale price of existing homes across the country was $311,000 in September, according to the National Association of Realtors, while the median sale price in Manhattan last quarter was $1.1 million, according to a Douglas Elliman report.

Jumbo loans dominate major urban markets, where housing is more expensive. The median sale price of existing homes across the country was $311,000 in September, according to the National Association of Realtors, while the median sale price in Manhattan last quarter was $1.1 million, according to a Douglas Elliman report.

Now, Manhattan homebuyers borrowing from Chase must pay at least 30 percent of the purchase price upfront. A down payment of 30 to 35 percent became the norm during the initial months of the pandemic, according to mortgage brokers. That translates to a down payment of at least $330,000 on a median-priced Manhattan home.

A spokesperson for Chase said the increased down payment requirement for Manhattan jumbo loans is “temporary” and a result of economic conditions in the borough. Unemployment is twice that of the rest of the nation, and a recent report on key-card access data from Kastle Systems International found that nearly 87 percent of New York City office employees continue to work from home.

Manhattan, which was already facing an oversupply of luxury condos, saw a 46 percent year-over-year drop in transactions last quarter. And as the pandemic drags on, failing retailers and restaurants threaten to depress home values.

Realtor.com’s chief economist, Danielle Hale, said the shift in lending standards stems from homebuyers ditching urban markets for the suburbs, leading to greater price growth in the latter. She said the trend is playing out in the most populated cities in the country.

“It makes sense that lenders are mindful of that and adjusting that lending criteria to that trend,” said Hale.

New York isn’t alone. A Federal Reserve survey of loan officers last month found that banks are tightening standards for most home loans across the board — especially for qualified jumbo mortgage loans.

Mat Ishbia, president and CEO of United Wholesale Mortgage, one of the largest nonbank lenders in the country, said he is following bank guidelines on loans of more than $1 million. This translates to loan-to-value ratios of about 70 to 75 percent.

“[In] downtown city areas, there is some concern,” Ishbia said. “There is a little bit less demand. … The prices are going down a little bit, or not going up as fast as the rest of the market.”

Susan Wachter, a professor of real estate and finance at the Wharton School, said it amounts to a flipping of the script for notoriously tight housing markets.

“The large megacities, they were the disproportionate success stories,” she said.

Before the pandemic, the biggest risk facing these cities was the lack of affordable housing, which was starting to slow growth in places such as New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Chicago. But as the pandemic and remote work have changed the desirability of these cities, Wachter expects prices there to drop significantly.

“New York is going to suffer, unfortunately,” she said.

Not every city (yet)

Metropolises where single-family homes dominate aren’t faring as badly.

Sales volume in Los Angeles last quarter was up about 14 percent year-over-year, according to the latest report from Douglas Elliman. And so far, lenders don’t appear to have any concerns with the city, where vertical living is far from the norm, according to Mark Cohen, a mortgage broker based in L.A.

“This market’s strong. Values are coming up because people are spending money on houses,” he said. “There’s a hot demand for houses because people want to have room.”

But Michael Nourmand, an L.A.-based residential broker who runs his eponymous firm, said he has run into problems with lenders when he has “move-up buyers” — clients looking to trade up to a more expensive home. Lenders often bar them from having a contingency on selling their old house.

There are ways around that, but they come with a cost. “When you don’t fit in the box, you’re going to pay a higher interest rate,” Nourmand said.

The most difficult aspect of Covid-era home lending in L.A. concerns verifying borrowers’ income, which has been complicated by this being an unusual year for many Angelenos. Cohen noted, for instance, that many people in the entertainment industry saw their income disappear for a few months earlier in the year.

“They love people who are employed,” said Nourmand. “So what I mean by employed is a Disney executive with a W-2.”

Fried, the Miami mortgage broker, recounted an instance where a lender put the kibosh on a loan after taking more than two months to review it. For another client, he had to produce three years of tax returns. Other clients have been asked for a certified letter from an accountant detailing how much they will earn in 2020.

But apart from the delays and additional scrutiny, he said, there haven’t been major changes in home lending because with few homes on the market, their values have remained high.

“The concept of a softening residential market has not yet made its way into the underwriting to a complete degree,” he said. “The lack of supply is really, really holding things up.”

Single-family home sales surged more than 70 percent year-over-year last quarter in Miami Beach and the nearby barrier islands. There were also major annual gains in sales volume of homes in Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach, Florida.

Zillow economist Matthew Speakman doesn’t believe tighter lending criteria will dampen buyer demand. He noted a significant uptick in L.A. and Miami properties selling above asking price in September.

In L.A., 33 percent of September sales were above ask, compared to 21 percent a year earlier. In Miami, the number increased to 8 percent from 5 percent, according to Zillow.

Even in New York City, some lenders are confident that once the pandemic ends, values will recover.

“We know the New York City market very, very well, which is why we are not pulling back on our guidelines,” said Alan Rosenbaum, CEO of nonbank lender GuardHill Financial. He believes that an effective vaccine will bring values in the city back to pre-Covid levels and appreciating as before.

“We’re the contrarian,” he said. “The big banks aren’t lending. We are.”

The bottom line

What does all this mean for homebuyers? They have to fit a very particular bill to take advantage of the current rate environment.

Lenders are generally looking for several years’ worth of tax returns; a steady, salaried job in the same industry for at least two years; a high credit score; and highly liquid assets, mortgage brokers say.

But that’s a tall order when nearly 6.8 million people are out of work.

The disparity between homebuyers who can and cannot secure cheap financing may seem minor as the housing market continues its upward run. But some economists and industry insiders are sounding alarm bells that differing access to credit exacerbates stark inequality in America.

“If you lost your job during this recession, you’re not going to get approved for a loan,” said Redfin’s Fairweather. “The people that are able to take advantage of low rates [are] the people who have the best credit histories; they have the highest incomes.”

This reflects what Wharton’s Wachter described as a K-shaped economic recovery, in which the wealthy bounce back more quickly than lower earners.

But others argue that tightening the screws is what responsible lenders should do.

“You can’t have it both ways,” said Ishbia of UWM. “To change those rules puts you back in the ’07, ’08 world [of reckless lending], and that’s not what anyone would want or is interested in.”

Hale, of Realtor.com, agreed, noting that lenders’ additional scrutiny of borrowers means those who do get loans during the Covid era are going to be “higher-quality, better-qualified buyers.”

Wachter noted that an uneven recovery in the housing market poses broader problems.

“What we’ve seen in my research is that the inability to buy into a community with jobs is keeping mobility down and keeping people from moving to markets where there’s job growth,” she said. “That’s going to hurt the overall economy.”

MBA’s Kan agreed. “You need the lower end of the market to move up eventually,” he said.