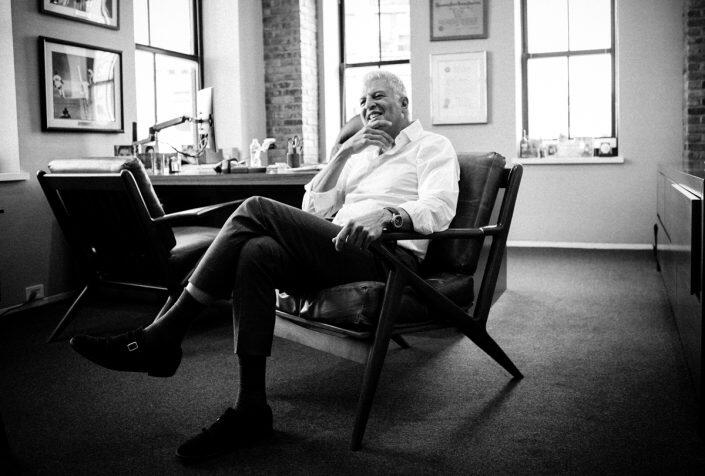

Among New York developers, there’s a certain conceit that goes with the drive and desire needed to reshape a city. Albert Laboz, though, has managed to stay humble.

With a portfolio of 75 properties, Laboz has cemented himself as a key player in New York retail. His firm, United American Land, specializes in the redevelopment of landmarked buildings. It has revitalized fixtures including the Decker Building, home to Andy Warhol’s Factory in the late 1960s, and breathed life back into the historic Fulton Mall, where it brought in Brooklyn’s first H&M.

Yet for Laboz — aptly, reading “The Power Broker” — development “in an overbuilt metropolis” does not mean you have to “hack your way with a meat ax,” as Robert Moses liked to say. His strategy instead relies heavily on a commitment to harmony — marrying progress with history, a new building with its neighborhood.

Mention his latest projects and the developer lights up. Today, his mind is on Canal Street. On the heels of an abysmal stretch for retail in the city, he is set on reviving the strip in Lower Manhattan. He commissioned experimental artists to occupy vacant storefronts and attract the type of young, chic brands characteristic of his Soho portfolio. If a handful of freshly inked deals that include the restaurant La Mercerie, inside Roman and Williams Guild, and fashion brands Drake’s and Knickerbocker are any proof, it seems to be working.

What attracted you to historic buildings?

That’s where the opportunities were. We love architecture, love design and love preservation. So it all falls into place. And that’s what tenants like. You can always build some glass building, but it’s not as interesting as something that has a tremendous amount of history, character, just general vibes.

Aren’t the regulations a pain?

Oh my God. It takes the simplicity level from zero to 10, zero being the easiest. We had a building in Jamaica. There was a lot line — the line between two buildings — we had to take it down. The [Landmarks Preservation] Commission made us take down each and every brick and save it and restore it. No one’s going to see the wall. So it’s incredibly painful. But it’s rewarding.

Did that come into play with the construction of Soho Mews?

That was a whole different story. We had a lot of money in that building, millions in personal funds. And we were doing phenomenal until something called subprime came along. We got over the magical 15 percent of sales. Then, all of a sudden, we had these lawyers — nocondo.com — trolling our buyers like ambulance chasers. No one’s closing. They’re asking for 30 to 40 percent discounts.

So we went to the attorney general, and the whole city was watching because it was happening all over. Ours were the first cases that came out, and we won all 12. People lost million-dollar deposits. But we weren’t in it for deposits. We just wanted to close. So we adjusted the prices a little to reflect the market and we got out of it. We did OK. But it was quite a stressful time.

When you were redeveloping Fulton Street, were you worried that e-commerce would curb demand for in-store shopping?

Brooklyn is the fourth-largest city in the country if it wasn’t a borough: 2.5 million people. Brooklyn is the most under-retailed city in the country. So let’s unpack that. Long Island, you have your usual malls, and in there you have all the usual suspects: Banana Republic, Gap, Victoria’s Secret. How many Gaps do you think there are in Brooklyn? In Long Island, you have like 13. In Brooklyn, you have three.

That’s why we felt confident and we’re not worried about online. Retail is an experience, and there’s a tremendous demand in the market by retailers to go to the outer boroughs now.

Did you feel panicked during the pandemic about commercial tenants not paying rent?

The problem is I had a lot of them go bankrupt. Neiman Marcus, Ann Taylor, we had plenty. So it was painful. But we were not over-leveraged, and we made it through. We’re in great locations, signing up the leases now, and it might take some time, but we’re confident.

Can I tell you a funny story about a crazy deal?

Yes, please.

So about four or five years ago, I was competing on a building owned by this woman. My friends all wanted to buy it. And she did not want to give us any information on the building. No leases. It was a one-story, dumpy building.

So I went to the lawyer’s office just to take a look at the leases. We did our own due diligence. Usually, the way you do it is you sign a contract then you close 60 to 90 days later. And then you go with the financing. She says, “No, we’ll go straight to closing, no contract.” So we do. The lady’s daughter was there and she says, “OK, let’s sign papers, but we’re not signing papers until you wire us $30 million.”

We told her, “Hold on. You want us to wire $30 million to you and you’re not going to sign any papers? We’ll wire it to your lawyer.” She says, “No, you’re going to wire it to us.” So we said OK. I go to the title guy and say, “Make sure everything’s in order. “

I said, “Sign the papers right now. You hold it in your hand. And when the money hits, you release the paper.” So that’s what we did. I put my chair by the door, made sure she’s not walking out with the paper. And the deal went through.

Were you worried she was going to make a run for it?

No, but just in case. The thing that gives us an advantage as a family business is we have the ability to make decisions like that. To take a calculated risk. You know, an institution wouldn’t do something like that.

You work with your brothers. Are you the oldest?

Oldest, but most immature.

When did you all get into business?

Jason and I started in 1985. Jody came along when he graduated eight years later. My dad was in the business with a partner for 30 years, and in ‘91 he split up with his partner. There was a depression in real estate in New York City. So my dad and his partner took all their properties and they put them in two columns of equal value. They flipped a coin. My dad took Column A; his partner took Column B. Whatever was in the operating accounts, they just took. And that’s it. My dad came with us.

It sounds like a good divorce.

What I learned about it is, no nickel-and-diming. You could sit there fighting — you’ve got a couple dollars more, no, you’ve got a couple. No, let’s just move on and concentrate our energies on going forward.

When did you know you wanted to go into real estate?

When I was in law school at St. John’s. All I did was take real estate courses: contracts, mortgages, landlord-tenant. I said, “I don’t want to be a lawyer. I want to be a client.” But I did want to have that legal knowledge. Everything we do is law: leases, mortgages, contracts, litigation. You definitely need a lawyer. But I cut through the issues and understand what the main issues are without having somebody explain it to me.

Tell me about your dad.

My dad is my role model, all our role models. Came from the Depression. Came from nothing. He was a retailer. As a retailer, you’re in a position to buy a building. He realized that if he had a couple stores, he could sublet some out. And he made more money on subletting the store than he was operating his business. And it was like an epiphany: This feels like something to get into. So we got into it.

What did he sell?

He had a store in Times Square, a few stores on 42nd Street between Seventh and Eighth avenues. When the Deuce was the Deuce. We used to sell men’s clothing. The name of one of the stores was SuperFly. We used to sell these platform shoes. I worked there when we were kids. Used to sell to the O’Jays, James Brown, the Temptations, as well as anybody else who walked into the store.

How did that change you?

We’re all salesmen, right? Real estate people, we’re all selling ourselves. I learned how to sell shoes, suits. So that’s all part of the skill set that we bring to the table.

Where did you meet your wife?

We summer in Deal, New Jersey, and it’s the mating season. I met her at a party. We got married about a year and a half after, in ‘88.

What’s the vibe there in Deal, New Jersey?

What’d you hear about Deal, New Jersey?

Syrian Jews summer there. You all have houses. It’s Hamptons-esque.

In the Hamptons, you have these tremendous estates. In Deal, you don’t have that. You have big, beautiful homes. But they’re not like the Hamptons, because people go to synagogue on Shabbat and they’re within walking distance. It’s a lot closer. It’s kids playing basketball, tennis. Parties, beach, lots of charitable functions. It’s nice.

My father, as a retailer, worked on Shabbat, and we worked on Shabbat. When we were 16, they rented their first house in Deal and we said, “Beauty! We don’t have to work on Shabbat anymore. We’re going to take off on Saturdays.” And he said, “No, you have to work.” My mom says, “Yeah, Jack, come on.” [He says,] “Betty, stay out of it.” He says, “For every Saturday you want off during the summer, you have to work one Sunday during the school year.” That taught us work ethic.

But we became a little more religious as we got older.

Recently?

So my dad became very, very sick a few years after that. And that’s when we started making our own commitments and belief in faith. Especially when you deal with Covid, there’s a whole reset. You have to have a little more faith and believe that things are happening for a reason.

Does that alleviate stress?

I guess you’re at peace that way.

So your thought is, “It will be what it is.”

Well, no. Because I hate when a person says, “It’s meant to be,” because you have to create your own “meant to be.” We have free will. You’re in a position to make yourself better or make yourself worse. To help people or not help people.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve received?

My uncle told me, “If you have a problem that can be cured with money, it’s not a problem.” I don’t want to sound callous. But what I’m trying to point out is that if it’s something that’s solvable even if you have to beg, borrow and steal for it as opposed to something that cannot be solved, it’s not a problem.