Craig Solomon

It’s hard to pigeonhole Square Mile Capital. The investment firm has been among the most active players of this cycle in all parts of the real estate ecosystem, from construction lending to distressed opportunities to refinancings to ground-up projects. And co-founder Craig Solomon likes it that way.

His Manhattan-based firm made its name as a lender in the heady days of 2006 and 2007, when swashbucklers like Kent Swig were buying up Downtown and it seemed like the music would never stop — until it did. Today, Solomon describes Square Mile as a company betting big on “secular tailwinds”: It’s one of the nation’s largest owners of soundstage space and is both developing and financing major last-mile logistics projects in New York. In 2012, USAA Real Estate took a 49 percent stake in the firm.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

You went to Lehigh University. What is up with Lehigh in New York real estate? Marc Holliday, the Stacom sisters. Is there a specific reason for that? Maybe it’s like Avis. So people from Lehigh have to try harder.

You started off with your own real estate-focused law firm. Steve Witkoff talked about pulling 90-hour weeks at Dreyer & Traub and coming home with nothing to show for it. HFZ’s Ziel Feldman talked about how the discrepancy between his paychecks and what his clients made didn’t work for him. What was your motivation to switch over? It wasn’t about the paycheck. When Steven, for example, was at Dreyer & Traub, I was at Paul, Weiss. He saw the light earlier than I did. For me, it was about wanting to be an entrepreneur, wanting to be my own boss, if you will, wanting to build something from the bottom up. So when I left Paul, Weiss, I started in the real estate business and then experienced the real estate crash of the early 1990s and had a reboot. And that reboot included trying to put food on the table, which meant practicing law on my own account for a period of time.

How tight did it get for you financially? I’m not exactly a big spender, so I was living in a one-bedroom with my wife and my infant daughter. And she was living in the L of the dining area, which we turned into a nursery, and I was working at my kitchen table. I was lucky enough to land some of the early large portfolios of debt that were being acquired at a significant discount. For some odd reason, a number of well-known players today back then asked me if I would represent them. The problem was, I didn’t have a law firm. So I went from my kitchen table to hiring five lawyers, to taking office space, to creating a law firm.

One of your clients at the time was Jeff Citrin, who became your partner at Square Mile. In 2006 and 2007, you made quite a name for yourselves lending on high-profile projects [such as Kent Swig’s Sheffield57 and 25 Broad in Manhattan]. When the crash came, you had to deal with the fallout. What did you take from that that you bring to your work today? We were reasonably well-suited as opportunistic investors to know how to deal with friction in the context of a distressed environment. That was in the context of what was our first fund at that time, and we managed to turn a lot of money into a lot less money, to be honest. Certainly the situation with 25 Broad turned out to be a winner for us for a variety of reasons. But I would have to tell you that there were just as many where we lost money.

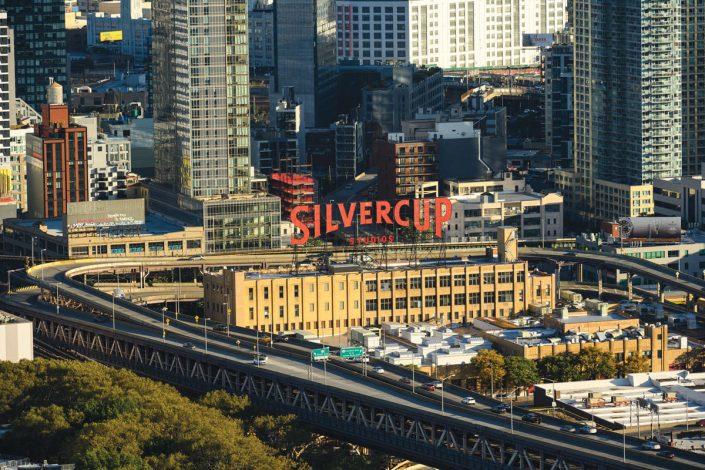

Silvercup Studios in Long Island City (silvercupstudios.com)

I went over the weekend to the mall, after a long time, and the experience was dispiriting. I bought a couple of things and then did the rest of my shopping online. The real estate world is shifting toward this last-mile problem. What do you hope to achieve in this space? (Square Mile is a lender on Dov Hertz’s last-mile project in Red Hook and an equity partner in a last-mile Bronx project with Innovo Property Group.) Part of the evolution of Square Mile has been a shift from opportunistic — if somebody knocks on the door with a transaction, we look at it — to more of studying the trends in the way we live our life. How do they translate into real estate, and where can we be investing where there are secular tailwinds?

Secular tailwinds. Blackstone uses the exact same phrase. I’m going to have to speak to them about that. But really what we mean is, how can we invest into asset classes which in the long run are sound fundamental investments? And so for us, that started with urban logistics. So when we had the opportunity to acquire the Whitestone Cinema site with Andrew Chung [Innovo principal] at what we considered to be a very attractive basis per square foot, a basis that would also work for other utilizations of that real estate, we were very anxious to do it.

In a partnership, are you more of a capital provider, or are you getting dirty as well? There are times when an operator who we partner on something with may not have the financial heft or the development experience in order to further a transaction, but has a great opportunity and a great idea, and it’s somebody that we think we can grow with. And then there are times when we really solely provide capital but leave the day-to-day driving to others. I find the process of taking an unentitled piece of land and creating the entitlements in order to unlock highest and best use to be painful. I personally could not be a developer.

Talk a little bit more about figuring out the capital stack. It’s something a lot of young developers struggle with. You can take the following to the bank: It’s going to take longer, and it’s going to cost more. If you judge every transaction by those two standards, I think you’ll find yourself in more conservative underwriting, more conservative debt capital structures and being able to withstand body blows, glancing or hitting the target, like Covid. Things just don’t unfold perfectly, ever.

You talked about secular tailwinds. One headwind that you’re all dealing with is, it’s very, very difficult to value an office asset now. Most companies are going to slash their office needs in the next 10, 15 years. So how do you see office as an asset? You’ve described why we’re in a market where there are precious few acquisitions going on because there’s no transparency on many of the issues. There’s no transparency on what the average square foot per employee is going to be. There’s no transparency on what corporations are going to do. Whether this 24/7 walkable sort of a lifestyle that’s been the underlying premise of the growth of major cities for 20 years, whether that’s going to be turned on its head. Real estate investors are fast followers. They’re not leaders.

So it’s difficult to buy an office building in New York City today because you don’t know whether tenants are going to renew and you don’t know what they’re going to renew at. And until transaction volume picks up and somebody steps up and does a lease, it’s going to be very hard to know. That is as against the backdrop of capital structures, of loan maturities, which when they start to hit will result in sort of the friction of a transaction.

A rendering of 2505 Bruckner Boulevard in the Bronx (2505bruckner.com)

You are now among the largest owners of soundstage space in New York and L.A. — close to 4.5 million square feet [with Hackman Capital Partners]. Netflix and Amazon and all the rest have a lot of demand for that kind of product. But are you worried at all about the rise of user-generated content [like TikTok] and how it might lessen the demand, long-term, for the space you’re offering? No one has ever asked me that question, and we’ve talked about our strategy to so many people in so many different contexts. We started being interested in the studio space when the attributes of that investment started to look and feel more like a real estate investment and less like a transitory operating business.

When you take the biggest streamers, they’re not going to deploy their balance sheet into owning real estate. They’re going to deploy it into content. So you have the supply, that was number one. Number two was, whereas the old studio business would be short-term licenses, the Netflixes, the Amazons, the Disneys want to control the space themselves. So those six-month leases started giving way to three-year deals and five-year deals and 10-year deals. With credit.

And the last thing that happened was [streamers saying], “We just don’t want standalone studios. We need production support. We want our talent onsite. We want our creatives onsite. We want a campus-like setting.”

To your question: We do not buy an asset that we don’t look to the alternative uses of that asset. And we don’t see it in the future, just based upon the demand, the supply/demand imbalance, the forward productions for the rental of lighting and grip. But we always look at what’s our downside in terms of an industrial play. It’s not expensive to reposition. And we’re focused on the best markets, which almost definitionally, in terms of infill, have alternative uses associated with them.

Are you starting to see any pandemic-related language show up in loan documents? People are getting more specific about a pandemic as a force majeure event. But other than that, we’re not really seeing it.

I wonder what that does for you as a lender. That’s like saying, if you’re in a 500-year floodplain, are you not going to make a loan? At a certain point, you’re dealing with these once-in-a-generation kind of events. And if you allow yourself not to be a net investor as a result of that once-in-a-generation event, then you don’t really have a business.

You made quite a big loan on an Astoria project [$280 million for 30-77 Vernon Boulevard]. That sort of giant rental is going to see depressed rents for a while. What are your thoughts on that space? I think that what we’re experiencing in multifamily in New York City today is a historic decline in occupancy, simply and solely because there are no renewals. Leases are expiring. We’ve seen folks leaving the system.

In New York City, you could take to the bank that you’re going to be 95 percent, 97 percent occupied. And now you can take it to the bank that you’re going to be in the mid-80s for the time being. Eventually you’ll absorb the vacant units. That will require rent concessions. The market will find its place … But that will take some time, whether rents are down 10 percent for the next three years, and then return to pre-Covid levels, and then start their march forward. Who knows?

Greed has a very short memory. New York City continues to be benefited by huge demand drivers, whether that be universities, the advertising industry, the legal industry, the financial services industry, the creative arts. These things aren’t going away. They’ve never gone away in the past.

But with time come alternatives. That’s being tested now. That’s totally being tested. If the college grads stop wanting to come to New York and to San Francisco in favor of Nashville, and Austin, and some of these secondary cities, then I think you set the template for a fundamental change.

I think that we will go through this process, and we will come out the other side. And the impacts, I think, will not spell the end of New York City as one of the great cities in the world, no more than London will no longer be one of the great cities of the world. But I think there will be changes on the margins.

I do think that the so-called secondary cities, especially ones with friendly climates, will find a wind at their back over the coming years … The much bigger risk are some of the social issues that we face, and some of the taxation issues that we face.

New Jersey just announced a millionaires’ tax. There’s a reason why Appaloosa, which was one of the great hedge funds, New Jersey-based, there’s a reason why it’s no longer New Jersey-based. You’re going to see more and more of that, and you’re certainly seeing that in California, and that’s disconcerting. And then there’s the income gap and all the issues that we talk about all the time in the context of a political environment, which is, for lack of a better word, not moderate in its approach.

How do you navigate that? I think if you have a dollar at risk in Lower Manhattan, you have to think about sea-level changes. Climate change is of massive concern. I think it can be turned into a positive, to a job creator, as we think about infrastructure projects to protect that which is already at risk, and then to create new industries, new technologies, so that we can reduce our carbon footprint further.

The thing that I’m worried most about is a brand of socialism where that delicate balance between a safety net for all gets tripped to the point where entrepreneurism sort of starts to get sucked out of the system. If one can’t be rewarded for their own initiative, and if creation of wealth is a negative, then I think we all have challenges.

Is there some degree of complicity from the wealthy, to have contributed to that environment, to the point that there’s such a toxic dialogue between the haves and the have-nots? Of course. I absolutely do. But I also think sort of there’s a reaction-action thing going on. Sort of that liberal smirk that many moderates and conservatives can’t tolerate. But yes, I think we’re all complicit. Things like Covid, and the social unrest that we’re all experiencing … The pot has boiled over, and the top has fallen off, and now we all have to be part of that solution.

Pre-Covid, I would travel the world trying to raise capital and talking to our investors, and they would look at the problems that we have in this country and say, “You’re the leading light. You’re the shining star. You think you have problems?” And that’s why you see all these flows of capital into this country. They come into this country because as flawed as we are, with all the challenges we have, which we must face, we still are the best of the worst.