Barneys’ former space on Madison Avenue was hanging by a thread.

A $76 million balance on the building’s debt, which Ashkenazy Acquisition took out in 2010, was set to mature in July. And after Barneys filed for bankruptcy and shut down all of its stores this February, Ashkenazy was forced to tap the retailer’s letter of credit to make debt service payments on its securitized mortgage backing the property at 660 Madison Avenue.

The private landlord reached out to Wells Fargo, the loan’s special servicer, to request more time, and last month the debt was modified to come due in January 2022, according to notes on the CMBS deal.

That extension gave Ashkenazy another year and half to figure out a repayment plan — one of the more significant loan modifications granted by a servicer since the pandemic started to put enormous stress on property owners in March.

A representative for Ashkenazy did not respond to a request for comment.

The data firm Trepp recently noted that the appraised value of the property had climbed from $222 million when Ashkenazy took out its mortgage 10 years ago, to $320 million this August, which “should give investors some additional confidence that the loan will ultimately be repaid.”

Many other borrowers in New York and other markets have only received short-term forbearances since the pandemic hit and now find themselves looking for more permanent concessions to manage their debt. At the same time, about $56 billion worth of loans — more than 10 percent of the entire CMBS universe — were in special servicing as of September, the highest level since 2013, according to Trepp.

When borrowers began facing the risk of missing payments en masse due to countrywide lockdowns, they scurried to renegotiate with their lenders and come up with quick-fix solutions like deferred payments.

But insiders say many property owners have failed to recover as those short-term agreements expire and lenders are now deciding whether they should deal with troubled assets through note sales or foreclosures, or try to work through loan modifications.

“I think everyone who did a three- to five-month forbearance, especially with hotels and retail, was doing open-heart surgery,” said Iron Hound Management’s Robert Verrone, one of the leading troubled-loan workout players in the country. “I think they’re all going to be circling back around for full workouts.”

Verrone said he’s currently engaged in about 50 different workouts — with solutions ranging from amortizing debt over a longer period of time to negotiating over lowering a loan’s principal.

Negotiating loan workouts promises to be a lucrative business in the years ahead, and the field of dealmakers branding themselves as specialists is growing. Due to borrower obligations to bondholders on CMBS deals, for one, securitized commercial mortgages often involve highly complex negotiations.

“If you’re trying to negotiate a forbearance [on a CMBS loan], you definitely need an adviser,” said David Eyzenberg, head of the boutique investment banking firm Eyzenberg & Company. “There’s a special knowledge base involved there.”

A few years ago his New York-based firm launched a debt restructuring group headed by Robert Ginsberg, who during the last financial crisis negotiated workouts on $2.5 billion worth of CMBS loans at the investment management firm Torchlight Investors.

“It’s been a pretty decent practice for us,” Eyzenberg said of his firm’s workout arm.

Banking on hope?

One tactic that became popular following 2008’s financial crisis — which some expect to make a big comeback — is the use of “hope notes.”

That’s when a lender splits a mortgage into two pieces: an A note that has a lower principal than the original loan and pays interest and a B note that pays no interest.

The idea is that it allows the borrower to make smaller interest payments and helps the lender recover some of its money. And the B note is the one the lender hopes it’ll get repaid on if the property recovers.

But many of the B tranches on hope notes became virtually worthless as properties failed to bounce back from the Great Recession, according to reports at the time.

As was the case back then, special servicers today are less likely to grant a second forbearance on a CMBS deal than most banks and other balance sheet lenders that still have debt on their books.

The number of forbearance agreements on CMBS loans has surged in recent months, though. In September, there were 800 securitized loans in some kind of forbearance period with a total balance of $31.2 billion, up from 400 loans totaling $16.6 billion in July, according to Trepp. The highest concentration of those loans was on hotels, which made up 64 percent of forbearance agreements, while retail followed at 28 percent.

Among the loans in forbearance is a $40 million mortgage that Barry Sternlicht’s Starwood Capital Group borrowed against a portfolio of 65 limited service hotels around the country with more than 6,300 rooms. Starwood put in a request for Covid-related relief in September, according to Trepp, and both sides were working toward a solution.

A representative for Starwood did not respond to a request for comment.

In South Florida, Charles Neiss’ Holiday Inn Miami Beach hotel was working on a loan modification in September that would allow the property to tap reserves to make partial loan payments on its $26 million mortgage, according to Trepp. And in Los Angeles, Wolff Urban Management engaged a workout adviser to negotiate a potential modification to a $27 million mortgage on its 213-key Courtyard hotel in Sherman Oaks, according to servicer notes.

In Manhattan, the owner of a retail condo in the Meatpacking District asked for relief after its tenant, the trendy clothing shop All Saints, shut down its store at 415 West 13th Street.

All Saints stopped paying rent in March and its parent company filed for bankruptcy protection in the U.K. in June. The property owner, a REIT managed by Germany’s DWS Group, made a request in August for a forbearance period of six months. A representative from DWS did not respond to a request for comment.

The latest servicer note, however, reported that the lender was “monitoring the tenant bankruptcy” as it discussed possible paths forward.

Clearer paths to repayment still remain elusive for many borrowers and lenders, though, as predictions about what the recovery will look like in six months don’t seem to have any more certainty than the predictions made six months ago.

Back then it was “convenient” for special servicers to say they’d do a short-term fix and see what happened in a few months, said Robert Brasfield of Atlanta-based asset management firm Trimont Real Estate Advisors.

“Now we’re six months into this, and maybe it’s not as convenient to say that,” Brasfield said. “But there are still a lot of unknowns.”

The specialists

While the Covid debt crisis promises to keep many borrowers and lenders up at night, a handful of industry players stand to gain from all the distress.

A growing number of negotiators are carving out a niche for themselves as workout specialists who work on behalf of borrowers to figure out loan modifications. In most cases, their backgrounds working as lenders, they say, means they know all the devils in the details.

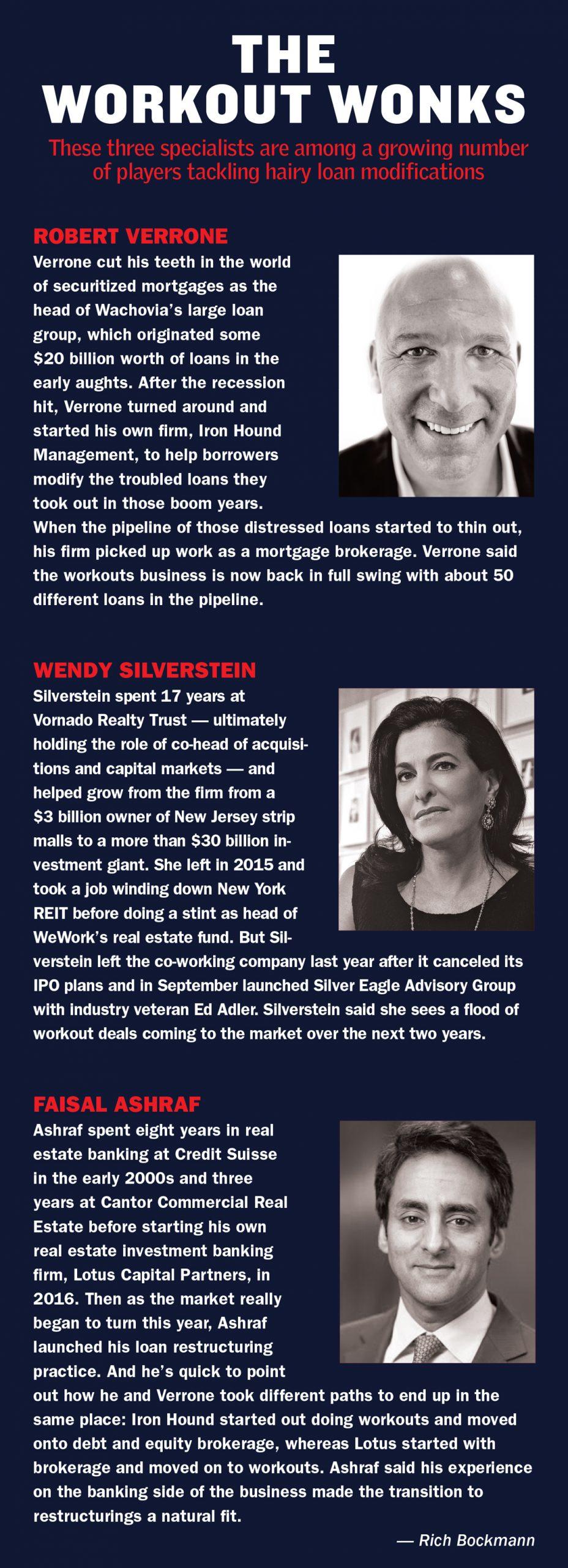

Iron Hound’s Verrone is, perhaps, most well known of the group. The former head of Wachovia’s large loan group launched his own firm in 2009 and made a name for himself as a workout specialist on deals including the Kushner family’s loan at 666 Fifth Avenue in 2012.

Now, with a cycle of workouts under his belt, Verrone said he realizes these modifications are more complex than he thought they’d be at first and acknowledged some of his own naiveté when he first got started.

“I didn’t truly understand how long a workout took,” Verrone said, adding that such negotiations can last six to 12 months. “I probably got my ass handed to me the first couple of years.”

Faisal Ashraf, a debt broker whose clients include Michael Shvo and Joe Chetrit, recently launched a restructuring advisory business at his firm Lotus Capital Partners. Before co-founding the real estate investment banking firm in 2016, he spent years working at Credit Suisse and Cantor Commercial Real Estate.

“I spent 22 years structuring complicated debt deals,” Ashraf said. “I have relationships with lenders and most servicers.”

Ashraf added that he sees a lot of opportunity for small shops like his to work on workouts. Loan modifications take esoteric skills that not all brokers have, making it harder for the large real estate service firms to scale the business up, he argued

“You don’t see the Eastdils and the JLLs wanting to be in this business, quite frankly,” he said.

It should be noted that some commercial brokerages like CBRE already offer loan services to both lender and investor clients, while others like Meridian Capital Group have been looking to enter the workout space. A handful of real estate law firms also advise on loan modifications.

But one factor that might keep some brokerage competitors out, Ashraf said, is that the nature of workouts likely puts them in an adversarial role with lenders. In turn, he said, many debt brokers may think twice about negotiating too rough and getting on their bad sides.

At the same time, it’s not just borrower-side specialists who are working on troubled loans. Timothy Little, chair of the real estate department at the law firm Katten Muchin Rosenman in New York, said he’s been doing loan workouts since the ’90s, mostly for his balance-sheet lender clients.

Little said those getting into the workouts space, especially on the CMBS side, should get used to bumping up against each other. “There are not that many special servicers,” he said. “It’s a small world.”

Two other industry veterans making a go in the workout space are Wendy Silverstein, a former Vornado executive who recently spent a year as co-head of WeWork’s real estate investment arm, and Ed Adler, a former Deutsche Bank lending boss.

Silverstein and Adler teamed up this fall to launch Silver Eagle Advisory Group after Silverstein got an offer from Meridian to join the debt brokerage and do restructuring work. Silverstein instead decided to start her own firm, which now has a servicing agreement with the commercial brokerage, and said she predicts plenty of business in the upcoming years.

“I think it’s something that will be in full force certainly in 2021 and probably well into 2022,” she said.

Trimont’s Brasfield — who represents the lender side on debt deals — said it can be a big boon for borrowers to have a specialist workout their debt deals, especially the more complex ones.

“There’s a real need for an advocate who knows how to navigate through the process,” Brasfield said, “and structured finance is very much a process.”