If you’re having trouble getting a hold of David and Simon Reuben, don’t take it personally. They’re just very, very private people.

The billionaire brothers have given one on-the-record interview in the 21st century, and promptly sued the publication for libel. They never appear on video, and the same handful of photos from some gala offer the only glimpses of them on the internet. They, like many people who’ve worked with them, declined to be interviewed for this article.

As one top retail broker who didn’t know he was on the record put it, “Nobody knows who they are or what the fuck they’re doing.”

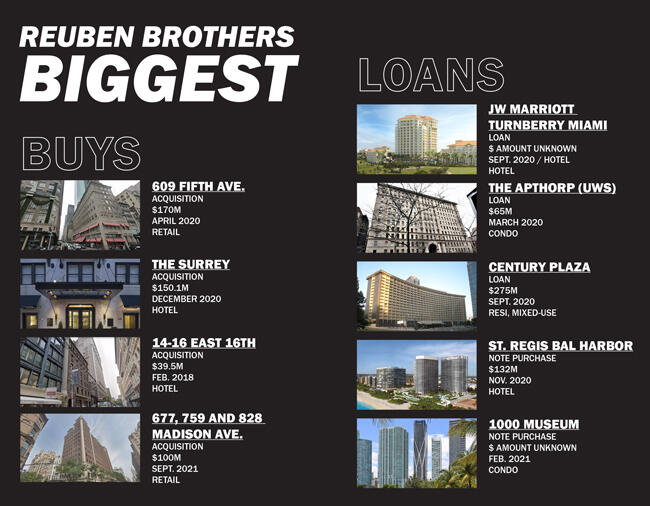

But what we do know is this: The Reuben brothers have emerged as the most opportunistic buyers of trophy New York real estate in Covid times, descending on Manhattan seemingly out of nowhere to acquire some of the city’s most coveted retail and hospitality properties. Since January 2020, the brothers have put about $4 billion into the U.S. real estate market through debt and equity investments.

They’ve snapped up assets such as the Surrey hotel, a prime Fifth Avenue retail condo and three buildings along Madison Avenue, snagging the properties at handsome discounts. They’ve also become crucial financiers to developers on properties ranging from the JW Marriott Miami Turnberry to Century Plaza in Los Angeles. Their quick execution and deep pockets have made them the first port of call for sellers hoping to offload trophy office and retail buildings, and a beacon of hope for deal-hungry brokers and cash-strapped landlords. And they’re far from done.

“We are active when markets are turbulent,” said one insider familiar with the company, “and continue to have the cash available to [invest more] should the right opportunities present themselves.”

Saying the Reubens have some cash available is like calling the ocean damp. The brothers sit on a gargantuan pile of money, and have leveraged it to buy and finance top-tier properties across the U.S. without shouldering any mortgages or outside loans. They control a £21.5 billion ($29 billion) fortune, making them Britain’s second-richest family, according to the Sunday Times of London’s Rich List. (Bloomberg’s Billionaires Index pegs each brother’s net worth at a more modest $6.7 billion, which would buy them 85.2 million barrels of crude oil.)

They’ve made headlines for how they spend that cash, whether it’s attempting to buy soccer club Newcastle United and the New York Mets or endowing their own college at Oxford University. But some of their flashiest purchases in recent years have been New York brick and mortar.

Born in Mumbai to Iraqi Jews, the octogenarian brothers have spent decades amassing their fortune from bases in Geneva, London and Monaco. But even now, as they stretch their empire across the Atlantic, remarkably little is known about David and Simon Reuben.

From Russia with love

The Reubens pulled their first fortune from the dirt.

After moving to London in the 1950s, the brothers split off into different trades: Simon imported carpets and dabbled in real estate, while David dealt in scrap metal. By the 1980s, they combined forces and set their sights abroad.

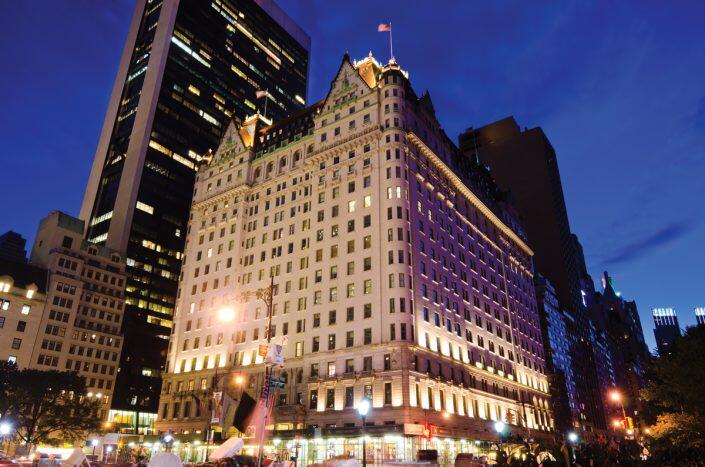

The Reubens made a big splash in 2015, when they bought the debt on the Plaza Hotel (IStock)

In the years after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, something between market and mob rule took hold. In that morass of early Russian capitalism, the Reubens grew their small metal trading company, Trans-World Group, into a major business.

The firm dealt in several materials, but aluminum was its cash cow, driving the firm toward some $6 billion in sales by its peak in 1997, according to an interview the brothers gave Fortune in 2000. They built their own infrastructure across Russia, shipping raw alumina imported from Australia across the Siberian tundra to the smelters that used to feed the Soviet war machine.

“We could have been the single biggest industrial group in the world,” David Reuben told Fortune. “We had the trucks, our own ports, our own shipping, and most of the [imported] raw material supply. Our competitors had to go elsewhere.”

By 1999, though, the party was over. Michael Cherney, their on-the-ground liaison, led a rebellion of Trans-World’s Russian factory managers, and anti-foreigner political headwinds compelled the Reubens to sell. But they didn’t leave empty-handed, netting $500 million for their biggest assets.

They had their first fortune and a fresh slate. Again, it was time to make money from the dirt. This time, they chose real estate in London.

Today, you could put together a handy sightseer’s guide to London built purely around Reuben Brothers-owned properties. Take a scenic jaunt through Hyde Park onto Oxford Street and check out Hereford House, which includes the 130,000-square-foot flagship store occupied by fast-fashion retailer Primark. Head south toward Buckingham Palace and get lost in the 37,000-square-foot maze of boutiques at Burlington Arcade. A few blocks east, pop in for a drink at their In & Out Naval and Military Club, just a piece of the 1.3 acres of prime real estate they own in Piccadilly.

Pass through Parliament to get to your office at Millbank Tower, the glassy high-rise on the banks of the River Thames where the ruling Conservative Party based its operations for several years. (The Reubens are major backers of the party, with David’s son Jamie donating £815,000 to its candidates in the last three years alone.) Cap it all off with a night at the Mondrian hotel in Shoreditch, the trendy arts district where Amazon put its U.K. headquarters.

The Reubens list on their website more than 60 properties spread across some of London’s hottest districts. They remain active in the U.K., with plans to convert Millbank Tower into a posh condo and hotel set to break ground in 2024.

Big Apple of their eye

The Reubens had some prior exposure to American properties through their investments in Chelsfield, the British developer that has had operations in New York since 1990 and owns a piece of the former Sony Building at 550 Madison Avenue. But in 2015, the brothers upped their bet on the city.

That June, they purchased the combined debt for the Plaza Hotel, the Dream Downtown Hotel, and London’s Grosvenor House for more than $800 million. The Plaza has changed hands many times, but the Reubens came in at a time of particular turbulence: Then-owner Subrata Roy, CEO of the Indian conglomerate Sahara Group, had been arrested by Indian authorities and held on $1.6 billion bail for unpaid debts.

“When they bought the Plaza debt, they came more into everybody’s rearview mirror,” said Jeffrey Roseman, a vice chair at Newmark and a founding partner of the firm’s retail group. “Clearly, they had an appetite.”

The Dream Downtown

As the storied hotel hung on the brink, threatening to pull the Dream and Grosvenor House over the cliff with it, the Reubens saw an opportunity. It was a telling roadmap, a mirror of their strategy for future acquisitions: In times of crisis, good deals abound.

They leapt across the pond and made their big play for the Plaza. Just as quickly as they appeared, they fell back into the shadows and waited. It would be another three years before they pounced again, dropping $40 million for a medical office building in Union Square. Today, the property still sits in disuse; it will eventually become a luxury hotel, but the Reubens are in no rush to finish the job.

And then came the pandemic.

In April 2020, with retail foot traffic at its nadir, the Reubens paid SL Green Realty $170 million, or over $7,000 per square foot, for a retail condo at 609 Fifth Avenue. Eight months later, they shelled out $150 million, or nearly $800,000 per key, for the Surrey, an Upper East Side icon whose previous owners failed to keep up with rent payments. Nine months later, another $100 million dropped, this time on three retail hot spots on upper Madison Avenue from Vornado Realty Trust at a discount.

The purchases came at a particularly trying time for retail and hospitality. Average retail asking rents fell 11 percent year-over-year, marking the 15th quarter of decline in a row, according to CBRE. They’re now at their lowest levels in nearly a decade. Meanwhile, hotel markets from coast to coast have endured catastrophic losses, with revenue per available room in New York down 62 percent from pre-pandemic levels, according to a recent survey by the American Hotel and Lodging Association.

The brothers have focused their retail investments on two of Manhattan’s hardest-hit corridors, Madison Avenue and Fifth Avenue. The Madison buildings and two properties in Soho, which Vornado sold with them, were losing money, with street-level occupancy around 30 percent. On Madison Avenue, ground-floor space availability is up 25 percent in the last year alone. While Fifth Avenue has begun to recover its pre-pandemic foot traffic, it is still missing about a fifth of its typical shoppers, according to retail data firm Placer.ai.

It’s been a canny entry into a notoriously unattainable section of the market. And the Reubens are doing it in a way that only multibillionaires could, deploying hundreds of millions of dollars with no clear expectation of immediate returns.

In April 2016, retail-focused investment firm 60 Guilders and the Carlyle Group tried to make a similar play into luxury retail, shelling out $105 million for a prime Soho building even as the neighborhood battled a glut of storefront availabilities. Three years later, after attracting more lawsuits to Spring Street than tenants, the partners sold the building to SL Green for a $25 million loss.

The Reubens enter the market with a far different posture. With no outside loans to pay back, they can take their time and wait for the market to come to them.

“To be able to buy those trophy addresses and have the ability to just be patient with them — God, I wish I had that kind of money to be able to do that,” said Roseman.

“Retail, unlike office space in large part, is not fungible. Retail is very, very quirky, and that adage, ‘location, location, location,’ matters,” said David Green, co-head of the New York retail group at Colliers International. And when New York comes back, a prospect most in real estate view as a matter of “when,” not “if,” the Reubens will have a portfolio full of some of Manhattan’s most valuable retail and hospitality properties, all acquired on the cheap. They’re playing the long game.

“The Reubens are rarely sellers and almost always long-term investors. They continue to have substantial cash reserves for the right opportunities at the right time,” said another person with direct knowledge of company plans.

“It’s a brilliant time to come into New York now,” said Roseman. “You’re still not gonna steal anything, but you’ll make a better deal than you would two years ago. And in three, four, five years’ time, it’ll pay dividends for sure.”

“Bring your money, get your deed”

At the end of 2020, the Surrey was barren. International borders were closed, and only the bravest Upper East Siders dared leave their co-ops. Nobody luxuriated in the hotel’s custom Duxiana beds or its soaking pools. As the city hunkered down, its hotels emptied out.

But even in this state of abandonment, the property had its suitors. After wresting control of the building from an involuntary bankruptcy, the hotel’s longtime ground lessors, Surrey Realty Associates, had been shopping it around in condo-developer circles. It was a handsome, recently renovated trophy in one of Manhattan’s top ZIP codes. Virus notwithstanding, it had a lot going for it.

Meanwhile, its owners were anxious to get the property off their hands. In August, they had persuaded a judge to terminate Ashkenazy Acquisition’s ground lease on the hotel.

That September, it was looking possible that Democrats could take the House, Senate and White House — and with them, reform the tax code and levy capital gains taxes at far higher rates.

“I said, woah woah woah — if they have a trifecta, what’s going to happen to capital gains?” said one member of the ownership group, who requested anonymity to discuss the deal.

The pressure only increased with Democratic victories in November and a pair of Georgia Senate runoffs that threatened to tilt the balance of power firmly to the left.

“So, time to get rid of it quickly,” the owner said.

The owners set a date: Dec. 3. By the time it rolled around, they had four identical contracts out to major condo developers. To ensure the deal would close while Washington was still in flux, and to gain some leverage, the sellers chose to do a simultaneous contract closing. There would be no 30-day window between signing and closing.

As the ownership group member put it: “Come to the table, bring your money, get your deed.”

A competitive, simultaneous closing attracts a certain kind of buyer. They need to be well-heeled, able to pull together funds for an all-cash offer and be willing to relinquish the standard inspection period. They need to be comfortable with risk, which in this case meant assuming control of a massive, empty hotel in the midst of a pandemic. And, with three others holding identical contracts, they need to move quickly. One buyer checked all the boxes: the Reuben Brothers.

“They negotiate hard,” the ownership member said, joking that his saving grace was a price floor his partners had established. But the negotiations were amicable. “From my experience, they do a straight deal,” he said. “That’s more than you can say for a lot of people out there.”

So it was that on Dec. 3, 2020, as more than 200,000 people tested positive for Covid and the bottom for New York commercial real estate just kept falling out, the Reubens bought one of the city’s more notable hotels for $150 million, cash. They shaved $65 million off the original asking price — a 30 percent discount.

Now the Reubens plan yet another round of extensive renovations to make the Surrey an uber-luxe hotel. In May, they announced plans to partner with Corinthia Hotels, a European hotelier, on management and operations. Casa Tua, the Miami-based hotel and restaurant company whose Aspen outpost the Reubens purchased in August, will handle food and beverages.

It won’t open until early 2023, but a wait isn’t an issue for the Reubens.

“Everybody [else] had a little problem,” said the ownership group member. “The Reubens came and closed.”