Marc Holliday pumped his fists up and down, leading a chant of “SL Green! SL Green!” that caught on, somewhat awkwardly, on the trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

It was the week after Labor Day, and the REIT’s executives were on Wall Street to ring the closing bell and celebrate the 25th anniversary of the firm going public.

The CEO beamed as he rang the bell. SL Green President Andrew Mathias exaggeratedly swung an oversized gavel. Stephen Green, its founder and chair emeritus, cheered them on.

Afterward, Holliday talked up the end-of-summer return of office workers.

“We were over 50 percent last week, and we see that number increasing,” he told CNBC, citing companies like Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan leading the way in calling on employees to return to their desks. “I’m sure other firms are going to follow.”

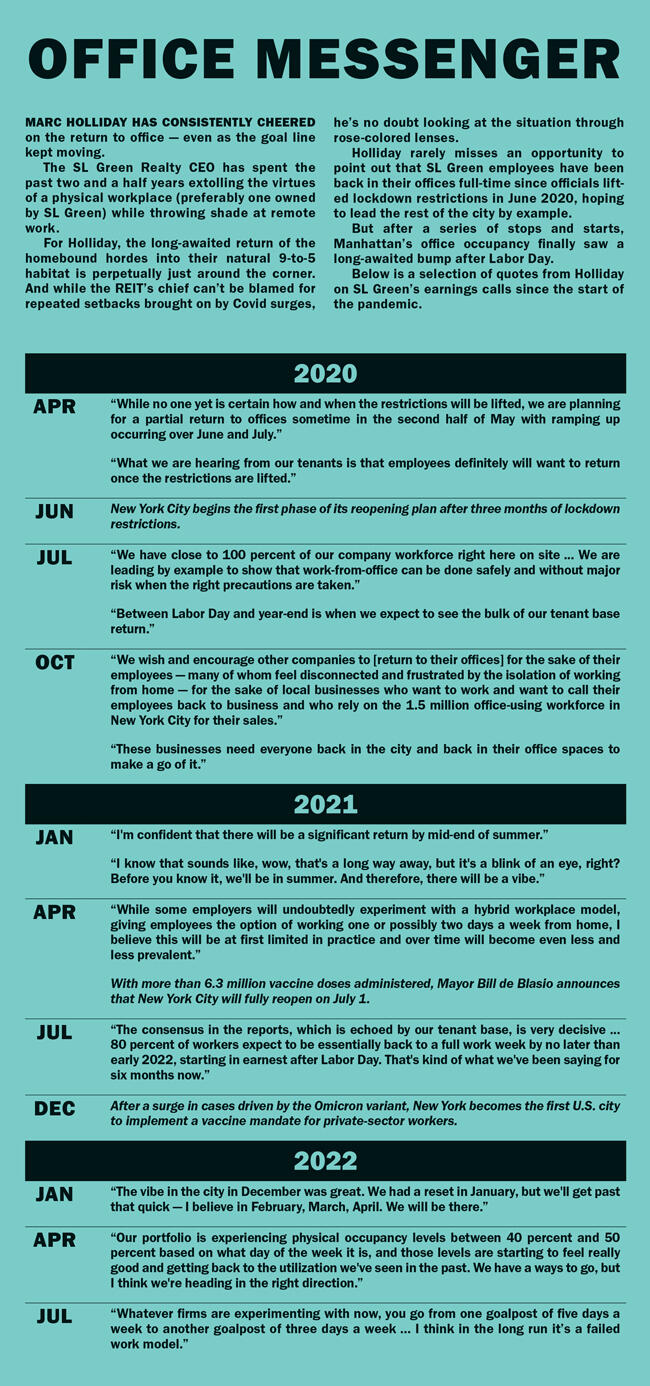

Holliday has been one of the back-to-office movement’s leading evangelists, and with good reason: His company is Manhattan’s biggest office landlord, and its portfolio represents something of a barometer for the city’s broader office market.

In the week after Labor Day, entry-swipe company Kastle Systems reported that physical occupancy in office buildings hit nearly 47 percent, up from 38 percent the week before and by far the highest since the start of the pandemic.

A survey by the Partnership for NYC covering roughly the same period put the figure at 49 percent. Subway ridership, meanwhile, climbed above 3.7 million riders in mid-September for the first time since March 2020.

It was cause to celebrate for Holliday and other landlords, who have suffered setback after setback in trying to lure office tenants back into their buildings. But with most workers returning only a few days a week, the victory may be a hollow one if it doesn’t translate into tenants leasing more space.

“Return to office is different from leasing, and leasing has definitely slowed,” said Piper Sandler’s Alex Goldfarb. “Right now, the market’s not great.”

“It’s unrealistic”

On a Wednesday morning in mid-September, a steady stream of professionals filed into the lobby of One Vanderbilt, SL Green’s brand-new, multibillion-dollar office tower next to Grand Central Terminal.

Many of the largest tenants in the REIT’s 26 million-square-foot Manhattan portfolio are back in their spaces, albeit on a limited basis.

Its biggest, the entertainment conglomerate Paramount Global, has had workers back since earlier this year.

“We have been back in the office since the spring with most people coming in about 50 percent of the time, or two to three days a week,” a spokesperson said.

The company, formerly known as ViacomCBS, leases about 2 million square feet at SL Green’s 555 West 57th Street, One Worldwide Plaza in Hell’s Kitchen and 1515 Broadway in Times Square.

Paramount did not, however, see a marked increase in attendance after Labor Day, and the company has no plans to require employees to come back more often.

The private equity giant Carlyle Group, which leases about 200,000 square feet at One Vanderbilt, has its employees in the office or traveling for a baseline of three days a week, give or take.

A spokesperson for Credit Suisse — SL Green’s second-largest tenant, with about 1.3 million square feet at 11 Madison Avenue — declined to comment on its office policy. But former CEO Thomas Gottstein, who resigned from the investment bank in July, said earlier this year that he didn’t think financial firms would ever go back to the office full-time.

“It’s unrealistic, and it is not what employees want,” he said at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, in May. “We are in a soft way trying to encourage people to come back, but it’s counterproductive if you push too hard.”

A war of attrition

As office tenants remain uncertain about how much space they’ll need in the future, the threat of a recession is further complicating landlords’ leasing efforts.

Firms leased 3.4 million square feet of Manhattan office space in August, the most since the start of the pandemic, according to data from Colliers, and the availability rate fell to its lowest level in more than a year.

But the month’s biggest lease, KPMG’s deal for 450,000 square feet at Brookfield Properties’ Two Manhattan West, was a downsizing. The Big Four accounting firm’s move to the Hudson Yards building in 2025 will consolidate its three current Manhattan locations, which combine for 800,000 square feet.

SL Green saw a bump in new deals in August, but leasing director Steven Durels said he wasn’t ready to call it a turning point for the office market.

“I don’t think one month is enough time to fully determine,” he told Bank of America analysts during a meeting in September.

Leased occupancy in SL Green’s portfolio stood at 92 percent at the end of the second quarter. That was about 1 percent below where the company projected it would be, and executives acknowledged it will be a challenge to hit their goal of 94.3 percent occupancy by the end of the year.

Durels said he saw encouraging signs from large tenants leasing big spaces. But what the market needs, he said, is for smaller tenants — those who go for 15,000 to 20,000 square feet at lower rates of under $75 a square foot — to get back to making deals.

“I think the new news is we’re starting to see signs of life in the commodity market,” he explained. “We need that part of the market to really come back to life to get stronger velocity in the overall marketplace.”

SL Green’s stock price, meanwhile, has struggled. The company’s market cap has fallen below $3 billion — less than its mortgage on One Vanderbilt. The company was the most shorted office REIT as of Aug. 15, with 10.8 percent of its shares shorted by traders, according to Piper Sandler.

An analysis by professors at Columbia University and New York University found that by the end of this decade, reduced tenant demand driven by remote work could erase about $45 billion from the value of the city’s office stock.

Activist investor Jonathan Litt, who has taken short positions on SL Green and other major Manhattan office landlords like Vornado Realty Trust and Empire State Realty Trust, tweeted after SL Green’s July earnings that its leasing activity raised concerns about demand for New York City office space.

“Great team dealt a difficult hand,” he wrote.

Porsches and F-35s

To get workers back into their buildings, landlords have reached into their bags of goodies and gimmicks.

Marx Realty recently unveiled a Porsche Taycan, a $100,000 electric car, for its tenants at its 10 Grand Central office tower. Executives in the 1930s-era building, which the landlord renamed in 2018 and gave a $45 million renovation, can use the car to chauffeur themselves or clients around Midtown.

At 7 World Trade Center, Silverstein Properties has a room full of F-35 flight simulators that tenants can use for team building or management training exercises.

Yael Ron, the company’s head of hospitality, said the simulators and other amenities the landlord offers are popular with tenants, who may already be more inclined than others to view their offices as a part of company culture.

“Class A buildings of course have higher amenities,” she said. “Those tenants are investing more in the quality of life of their employees for sure.”

A Silverstein spokesperson said that, portfolio-wide, physical occupancy ranges from 50 to 75 percent depending on the building and the day of the week.

The Gural family’s GFP Real Estate is raffling off NFL tickets for people who come to its offices. Jeff Gural said his company mostly owns older and smaller buildings, so it doesn’t make sense to try and stuff them with amenities.

Of course, whether all these goodies actually motivate people to come back to the office is unclear. Most tenants make decisions based on their bottom line and what’s best for their workforce.

“I don’t know if it moves the needle,” Gural said. “It makes it fun and differentiates us from other landlords.”

Piper Sander’s Goldfarb said that beyond the push to get back to the office, landlords like SL Green are dealing with concerns about crime in the city and the Federal Reserve’s efforts to tame inflation by cooling the economy.

“That’s not an environment where you’re going to want to see companies take more space,” he said.