The 57th Street pyramidBefore we allow ourselves to get carried away at the prospect of Durst Fetner Residential’s recently unveiled and startlingly original proposal for a residential development on the far west end of 57th Street, and before we congratulate ourselves on inhabiting a city that welcomes the most progressive strains of contemporary architecture, we should remind ourselves that this is still New York. And, if experience is any guide, the end result of this daring project’s lengthy approval process, involving the community board, the Department of Buildings, and anyone else who wishes to weigh in, may well be a piece of architectural product that is as dull and unremarkable as most others in the five boroughs.

For the moment, however, one and a half years before the developer hopes to begin construction and nearly four years before it is aiming to complete the project, we can allow ourselves to marvel at the audacity, if nothing else, of the project that has just rolled out of the studios of Bjarke Ingels. At 36, this Danish architect is remarkably young to be building anywhere, but especially in a city like New York, where seasoned veterans tend to show up during their golden years, with their most original work long past.

The project, which is intended to contain 600 residential units, is yet one more step in the piecemeal colonization of Manhattan’s Far West Side, the gradual transformation of the area from a commercial district that, half a century ago, was dealt a heavy blow with the evaporation of New York’s shipping industry. In place of that older district there is now emerging a gentrified area as upscale as any in the city. Thanks largely to the efforts of Donald Trump, the strip of the Hudson from 59th to 72nd streets was the first to be developed. In more recent years, 42nd Street has seen almost frantic development from Eighth Avenue to the Hudson. However, West 57th Street has been something of a laggard in this respect — until now.

Almost without exception, residential buildings in the five boroughs, and especially in Manhattan, tend to be boxy, rectangular affairs that inhabit their lots obediently and to the full extent allowed by law. If absolutely necessary, they will rise up on a tower over a base.

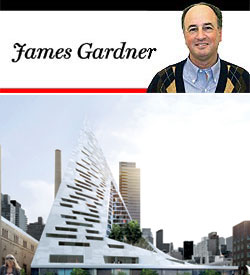

Instead of such standard fare, Ingels has conceived his residential structure as a torqued pyramid that springs from what looks to be a one-story base.

Rising up between 11th and 12th avenues, in the midst of preexistent cookie-cutter buildings destined to surround it, Ingels’ design reads almost like a Klingon warship establishing hegemonic control over the Far West Side.

The windows of the building are a syncopated series of slits arrayed across the pale, grayish-white façade. Aside from its overall shape, the most distinguishing mark of the building is a huge opening, almost a gash, in its center. It is as though, in trying to conceptualize the volume of the building, the architect has sliced and hacked his way through a watermelon, cutting it down to size and then neatly gouging a chunk out of its center.

Ingels is an alumnus of OMA, Rem Koolhaas’ renowned Office of Metropolitan Architecture, and this is surely evident in this proposal. Like the work of Koolhaas, as well as of Zaha Hadid, another former Koolhaas associate, Ingels is anything but organic in his approach to architecture. For him, design is entirely an affair of spiky, bristling, boomeranging angles in an idiom that reinterprets and deconstructs — to use the going word — the formal vocabulary of mainstream modernism and the International Style school of architecture.

But his approach is highly intuitive: There is no interest in context, and his overwhelmingly geometric forms seem to be generated by throwing one thing after another until something finally seems striking enough to have polemical force.

The source of such architecture in Koolhaas, Ingels and others of their clan, though it usually goes unacknowledged, is the Mod idiom of the ’60s. As such, even in such a youthful work as Ingels’ 57th Street design, there is a retro, historicist element.

In Ingels’ oeuvre to date, the results have been somewhat hit or miss. The play with volumes in a residential context can be seen in such earlier projects as the VM Housing and Mountain Dwelling projects in Copenhagen, Denmark. Both are stacked in unusual ways, sloping downward in a manner somewhat akin to the Durst Fetner development. A far better-looking effort is Ingels’ work on the Danish Maritime Museum at Helsingør, Denmark. The entire museum is built below grade in the form of a gash in the earth, similar to the cutout in the proposed 57th Street pyramid design. On the basis of photographs, that last project seems to have what, for this architect, is a rare and welcome sense of the materials used — in this case, poured concrete.

Ingels also deserves credit for attitude, at the very least, in his Helsingør Psychiatric Hospital in Denmark, which reads from the air as an eight-limbed steel-and-concrete arthropod.

As for 57th Street, the result is more striking than it is beautiful, though in the contemporary consumption of architecture, the distinction between beauty and striking effect is often blurred.

Though Ingels and Durst Fetner surely deserve high marks for initiative and daring, I am a little nervous about the emphatic way in which, if the present project is built according to the rendering, it will diminish the integrity of the street wall. Variety may be the spice of life, but I am unaware of any urban context in which the disruption of the street wall has a beneficial effect. But we’ve been down this path before: Few things gladdened the hearts of mid-century urban planners more than chewing up the street wall of some of Manhattan’s noblest avenues, on the assumption that not to do so was to invite tedium. The result is that scarcely a block in Midtown has preserved the street wall intact. Instead, developers gladly subjected it to jagged and unexpected recessions in exchange for the privilege of building higher.

And so, even though the ground floor of Ingels’ design may well fill up its lot, the swerving form that sits on top of it will create a disruption, a sudden intrusion of sky and emptiness in the place of masonry. That may prove to be somewhat unwelcome on 57th Street, one of Manhattan’s most important thoroughfares. Whether it is preferable to the usual fare of drab right angles remains to be seen.