From left: Mark Gordon of Tribeca Associates, Ron Burkle a stakeholder in Morgans Hotel Group, Gary Barnett of Extell Development and Tommy Hilfiger, who purchased the MetLife clocktower

For the last few years, investing in New York hotels was like scoring the Presidential Suite at the Plaza — an experience reserved only for a select few, primary real estate investment trusts. Indeed, as the stock market roared back, these publicly traded REITs were able to raise capital almost as easily as dialing up room service.

Recently, though, other types of investors — most notably management companies, private equity firms, government investment arms and hedge funds — have edged into the New York market, convinced, it seems, that hotel values in the city still have a ways to climb. That is despite the fact that hotels have already rapidly risen in value after taking a severe recessionary beating in 2009.

“It took a while for those outside the lodging industry to realize what was happening to New York lodging,” said Bjorn Hanson, a hotel specialist at New York University’s Preston Robert Tisch Center for Hospitality, Tourism, and Sports Management. “It has all created appeal for the nontraditional investor.”

With tourists and business travelers now back in force in Manhattan for more than a year, investors and developers have taken notice, Hanson said. Sure, room rates aren’t back up to their pre-recession levels yet, but in a city that by many measures still has a limited supply of hotels, occupancy rates have remained strong.

Indeed, hotel occupancy in Manhattan is projected by analysts to be as high as 85 percent for 2011, versus the low 70s in the depth of the recession. And, that’s close to the peak levels experienced in the 12 months before September 2008, when Lehman Brothers imploded.

More important, though, may be the economics of hotel deals: The spread between asks and bids has narrowed, analysts said. That, they noted, is a sign of greater activity and interest, and is like chum in the water for deal-hungry investors.

Plus, observers noted, with the now-seesawing stock market, there’s a sense that REIT stock prices may be vulnerable to drops, making it potentially difficult for those entities to use future public offerings as a way to drum up capital. So, with their competitors’ hands tied, private investors can now afford to play.

“The cost-of-capital advantage that public companies have is waning,” said David Loeb, a hotel analyst with Milwaukee-based private equity firm Baird. “Private capital has gotten more competitive” because bank-issued debt is becoming comparatively more affordable, he added.

The numbers are expected to begin bearing out this point soon.

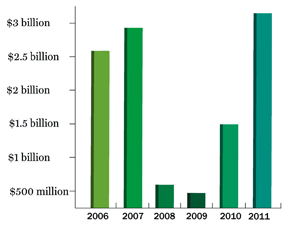

Total dollar volume of Manhattan hotel sales (Data from Real Capital Analytics. Only deals of $20 million and above were included. Data only includes existing hotel sales. The 2011 total is year-to-date.) In 2010, the buyers in six of the 12 biggest hotels that traded for over $50 million in Manhattan were REITs, according to data from the research firm Real Capital Analytics.

So far this year, REITs were also buyers in approximately half of the 13 deals to date, but analysts say that the second half of the year will tip the scales in favor of private investors.

Indeed, fashion mogul Tommy Hilfiger signed a contract to buy the MetLife clock tower building on the edge of Madison Square Park in May for $170 million, with plans to turn it into a hotel. And in July, Tribeca Associates, the group behind the Smyth Hotel Tribeca, purchased the former Donnell Library on West 53rd Street, in a partnership with Starwood, for $59 million, Tribeca Associates partner Mark Gordon confirmed.

Gordon’s company — which seems to be showing proportionally greater interest in hotel deals than other types of investments lately — is also looking to convert 170 Broadway from an office to hotel, according to news reports, though Gordon declined to comment on that deal.

Meanwhile, Aby Rosen’s company RFR Holdings has also been keen on hotel investments recently.

In June, RFR, which has been struggling at several of its projects, surprised many in the industry when it picked up the Paramount Hotel at West 46th Street for $275 million (see “Midtown hotel mania”). Though Rosen does already own a pair of hotels outside the city (and, of course, bought out partner Ian Schrager at Gramercy Park Hotel), this seems to represent a local push in a new direction for RFR, whose portfolio historically has featured offices and retail. In addition, in April, the Chetrit Group, known for office and rental addresses, bought the legendary Hotel Chelsea for $80 million, perhaps signifying a new focus for that company, too.

Even ground-up development deals are attracting new faces, like Gary Barnett’s Extell Development Company, which is including a massive Park Hyatt at its One 57 project on West 57th Street (see “Is One 57 the new 30 Rock?”). The 90-story tower, which will also include condos, is slated to become New York’s tallest residential tower.

In addition, Dune Capital Management, a hedge fund spun off from Goldman Sachs, bought the Upper East Side’s Mark Hotel in March for $190 million. Plus, the Kuwaiti IFA Hotels & Resorts joined investment agencies from Kuwait and Portugal to buy Yotel, developed by Related Companies, in June for $315 million.

Total number of hotel rooms in Manhattan by year (Data from PKF Consulting. Number of hotel rooms is as of Jan. 1 of each year.)And in June, grocery-store magnate Ron Burkle invested in the upcoming 168-room NoMad Hotel, in the gentrifying area at Broadway at West 28th Street. Burkle, who owns a stake in the Morgans Hotel Group, joined forces on this deal with the Sydell Group, a part-owner of the nearby Ace Hotel. Other Burkle-Sydell hotel investments should follow, Sydell executives say.

Meanwhile, last month Parkview Developers announced that a new hotel called the Out NYC, which will cater to the gay community, is under construction at 510 West 42nd Street, between 10th and 11th avenues. The project, which will also include a nightclub and lounge, will have 105 rooms. No completion date has been set for the hotel, but the lounge is scheduled to open this fall.

Whether developers are turning to hotels at the expense of other deals is unclear. Comparing lodgings to other assets, like offices, is hardly an apples-to-apples proposition, many analysts caution.

“Sometimes that kind of investing is not mutually exclusive,” said Cheryl Boyer, president of Lodging Advisors, a seven-year-old Manhattan-based consulting group.

In other words, it would be somewhat unusual for, say, Cornerstone Real Estate Advisers, the private firm that bought the Algonquin Hotel in June for $79 million, to have passed on the chance to buy a similarly priced office building, analysts said. For one thing, offices often require decade-long leases, where the rents are locked in, while the nightly room rates at hotels have lots of leeway to float, so the business models are hard to compare.

But it is worth noting that capitalization rates, which are a reliable way of determining the value of buildings, show that there may be better bargains to be had in the hotel market these days, said Baird’s Loeb.

To wit: For the last 10 months, the average cap rate, or ratio between the annual net operating income of the asset and the price paid for it, was about 5.4 percent for 16 of the 50 office building deals in Manhattan where the cap rate was calculated by RCA.

In contrast, the average cap rate for Manhattan hotel transactions over the same time frame was 6.7 percent.

To be fair, hotels normally have higher cap rates than office buildings. The inherent unpredictability of the hotel business means that they’re always a riskier real estate asset. Hence, the higher cap rate.

And while the cap rates of New York hotels have been dropping for the last three years, as the city’s tourism industry recovered and the hotel sales market heated up, they are still high compared to offices, which may be tempting to investors, analysts say.

“It’s a difference worth noting,” Loeb said.

The fever for hotels appears to be affecting smaller-bore investors, too. David Schechtman, a broker with Eastern Consolidated, is listing a new 43-room hotel on Allen Street in Chinatown for $19 million; it’s being marketed as a Howard Johnson’s, though the buyers could go with a different operator, he said.

In addition to the usual REITs, other investors have also been nosing around, including Extell, private equity firms, and one man who owns auto dealerships in the boroughs who has never owned a hotel before, Schechtman said. “He has watched neighborhoods grow up around hotels and is interested,” Schechtman said.

Does all this interest suggest that a bubble may be forming? Far from it, he said. “I think the market for hotels will be robust for another 36 months,” he predicted.