UPDATED, Oct. 1, 11:50 a.m.: As Bank of the Ozarks’ private jet lifted off from Little Rock, Arkansas, Dan Thomas geared up for another day of dealmaking. As vice chair of the bank, he oversaw one of the country’s largest construction lending operations and had become a financial messiah for major condo developers in New York, Los Angeles and Miami.

Seated shoulder to shoulder with him that morning was his boss, George Gleason. Over 14 years, the duo had built a unique lending operation that transformed the bank from a regional minnow into a national powerhouse that beat out JPMorgan and Wells Fargo in development deals. But as the Washington, D.C.-bound jet hit cruising altitude, Gleason gave Thomas an ultimatum: Step back as the bank’s lead dealmaker or lose $5 million in accrued compensation.

Miles above Texas, Thomas quit. “The plane turned around and we landed in Dallas,” he recalled in an interview with The Real Deal. “That was my last moment at Bank of the Ozarks.”

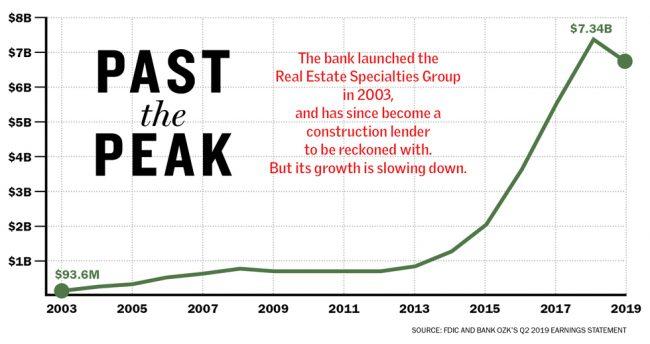

The July 2017 episode, which hasn’t previously been reported, coincided with the end of a decade of steep profits and rapid growth at the lender, which rebranded last year as Bank OZK. Its shares dropped 12 percent right after Thomas — who was seen as the driving force behind the bank’s real estate lending — left and have fallen further as the bank has struggled to maintain growth.

The July 2017 episode, which hasn’t previously been reported, coincided with the end of a decade of steep profits and rapid growth at the lender, which rebranded last year as Bank OZK. Its shares dropped 12 percent right after Thomas — who was seen as the driving force behind the bank’s real estate lending — left and have fallen further as the bank has struggled to maintain growth.

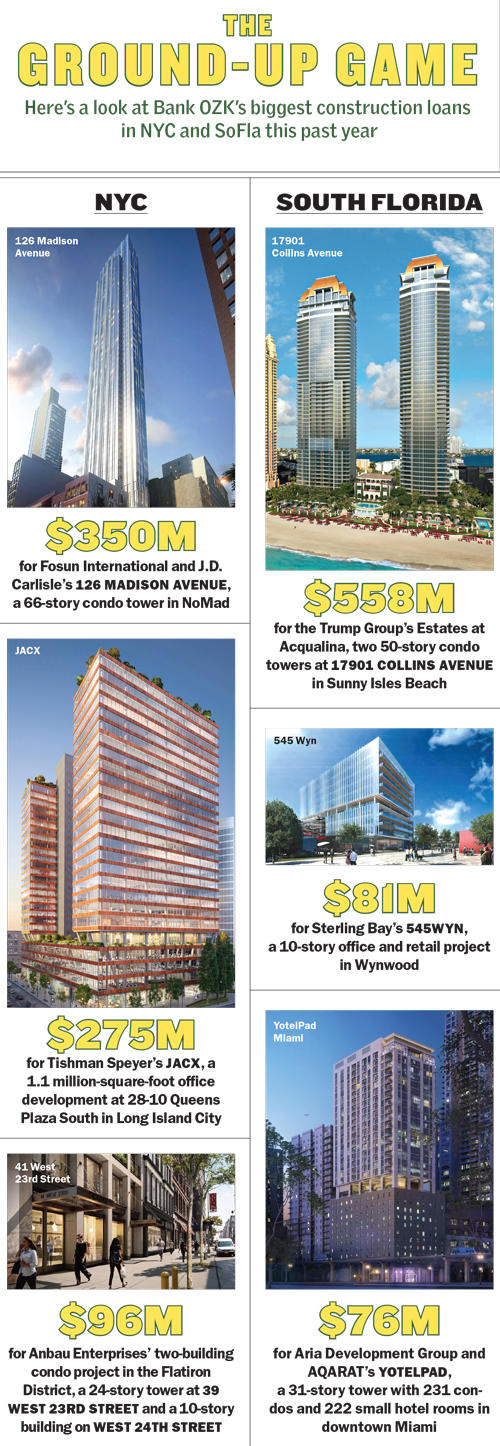

Gleason promised investors he would step into the void left by Thomas, but current and former employees say this hasn’t panned out. And as the bank’s deals get bigger and more complex — it closed about $1.37 billion in New York construction lending over the past year with developers such as Tishman Speyer, Extell Development and Lightstone Group — the real estate lending group has been hit by infighting and allegations of sexual misconduct and age discrimination.

Meanwhile, the environment in which the bank is doing its deals has changed. Congress has slashed stress-testing regulations on midsized lenders, and Bank OZK itself has taken an innovative approach to avoiding scrutiny: It engineered a change to Arkansas banking laws, allowing it to stop reporting to the Securities and Exchange Commission and answer to what experts believe is a far more lax regulator.

“Banks don’t willy-nilly switch regulators,” said Ken Thomas, a veteran banking consultant and longtime lecturer at the Wharton School. “This is a red flag.”

The looser regulatory environment, taken together with the tumult inside the lending group and increased competition for fewer deals, could potentially lead the bank to make riskier deals. Gleason, however, is adamant that won’t happen. He said that the bank is now seeing less opportunity for construction lending in New York City because of a drop in new projects and more gung-ho rivals.

“Lenders in certain markets are very aggressive on price,” he said on the company’s July 19 earnings call. “We’ve been just clear without exception that we are not going to sacrifice our credit standards.”

Small bank, big checks

Gleason was just 25 years old when he purchased the Little Rock-based Bank of the Ozarks in 1979, putting down $10,000 in cash and taking a $3.6 million loan. He took the lender public in 1997 and in 2003 was introduced to Thomas, an accountant and real estate attorney, whom he hired to lead a new Dallas-based lending operation known as the Real Estate Specialties Group.

Together, they crafted an aggressive real estate lending strategy around two core principles: The bank would always be the sole secured lender, ensuring it would be the first to be repaid. And the development team would have to cough up at least 50 percent of equity in a given deal before the bank made a loan, guaranteeing serious skin in the game.

To fuel this lending, Gleason figured he could build deposits by acquiring other community banks, envisioning a whole new business model for banking. Since the financial crisis, Bank OZK has acquired more than a dozen community banks in Florida, Arkansas, Texas and Georgia.

Emboldened by these acquisitions, the bank entered New York City in 2013, and by the end of 2014 its construction loan volume doubled to $1.5 billion. By 2017, with a mere $20 billion in assets, it became the alpha dog in its niche — large, nonrecourse construction loans for ground-up projects — often beating out the likes of JPMorgan and Wells Fargo, which together manage over $4 trillion in assets. It became the largest construction lender in L.A. County, the largest condo construction lender in Miami-Dade County and the third-largest construction lender in New York.

And it revved up just as developers saw other crucial sources of money, such as debt raised through the EB-5 visa program and Chinese institutional capital, fading away. Thomas landed on the Commercial Observer’s list of the top figures in real estate finance, and capital markets broker Simon Ziff told Bloomberg he considered Gleason “one of the most important real estate bankers in America today.”

And it revved up just as developers saw other crucial sources of money, such as debt raised through the EB-5 visa program and Chinese institutional capital, fading away. Thomas landed on the Commercial Observer’s list of the top figures in real estate finance, and capital markets broker Simon Ziff told Bloomberg he considered Gleason “one of the most important real estate bankers in America today.”

Ask me no questions

But all that growth and attention — the press dubbed Gleason “the Wizard of Ozarks” — came with some unwanted scrutiny.

In September 2011, auditors from the SEC asked questions about the bank’s accounting methods. In 2014, the agency raised concerns about its real estate lending, asking why its provisions for loans that could go into default jumped from 168 percent in 2008 to 492 percent in 2013. And in 2016, the SEC directed the bank to explain its underwriting process and how it tracked its real estate projects.

Others began to raise questions. Carson Block, founder of Muddy Waters Research and a prominent short-seller who exposed fraudulent Chinese companies, said in 2016 that Bank OZK’s high concentration of construction loans was susceptible to a downturn, and that to sustain itself it would need to keep buying more banks. In shorting its stock, he said the bank had an “ass-backward business model.”

Faced with mounting pressure, Bank OZK pulled off a regulatory sleight of hand that got the SEC off its back.

At the time, the bank had a holding company, a corporate structure used by major U.S. banks that requires them to report to the SEC and be regulated by the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and a state bank regulator.

But by shedding its holding company, Bank OZK would only be overseen by two regulators — the FDIC and the Arkansas State Bank Department — and would no longer have to answer to the Federal Reserve and the SEC.

The FDIC, which monitors the risk to a bank’s customers, would become the bank’s new primary regulator. But experts believe it has less rigid auditing standards and requires less risk disclosure than the SEC.

The FDIC, which monitors the risk to a bank’s customers, would become the bank’s new primary regulator. But experts believe it has less rigid auditing standards and requires less risk disclosure than the SEC.

The SEC “clearly flagged some concerns it had,” said Thomas Hazen, a securities professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. “As an investor, this clearly makes [Bank OZK] a much more risky proposition than an SEC-regulated bank.”

As the plan came together, Gleason faced a hurdle: In order to rid itself of its holding company, Bank OZK had to merge its holding company into its bank subsidiary, but Arkansas law complicated this merger. So in February 2017, the bank lobbied the legislature to introduce a bill that it said would “modernize” Arkansas banking laws, state filings show. The proposed bill included a clause that allowed the bank to complete the merger.

“We weren’t using our holding company, and we saw no reason to keep it,” Helen Brown, the bank’s corporate finance general counsel, told legal trade publication Modern Counsel.

Weeks later, an emergency clause pushed the bill forward to do just that. To complete the regulator swap, the final step amounted to a mere technicality: persuade the state Bank Department’s board, which is chaired by industry leaders, to approve the change. The bank shed its holding company — thus removing oversight by the SEC and Federal Reserve — in June.

Bank OZK’s tactic amounted to “regulatory shopping,” said Jeff C. Gerrish, a former FDIC attorney who is now a consultant and attorney to community banks across the country.

But Gleason characterized the move differently: “If you own a lake house but you never go there,” he later said in an interview with S&P Global, “and you’re paying taxes and insurance and maintenance on it every year but you don’t use it, it’s not much fun.” (The bank’s chief administrative officer, Tim Hicks, said the bank would not quantify the cost savings from the move.)

Jason Rapert, the Republican state senator who sponsored the bill, said in an interview that “Mr. Gleason has been regarded as one of the most intelligent men in the banking business in the country.”

“I’ve heard nothing but good things about Mr. Gleason,” Rapert added, “and the way he does business.”

The tussle

While Gleason was the poster child for the bank’s meteoric rise — his home, a 19th-century French-style mansion on a 105-acre property complete with a private chapel and fountains, is one of the largest in the state — Thomas, the head of the real estate lending group, shied away from publicity. Instead, he established himself as the point person for institutional landlords and developers, including Starwood Capital, JDS Development Group and Square Mile Capital. He was paid $4.7 million in 2016, behind only Gleason, who made $6.2 million.

Gleason was able to convince the Arkansas legislature to rewrite banking laws

“Basically, [Thomas] is the guy who made [Bank OZK] who they are today,” said JDS chief Michael Stern, who has borrowed from the bank for multiple projects, including 9 DeKalb Avenue, Brooklyn’s future tallest tower.

But in mid-2017, around the time the bank dropped the SEC, Gleason increasingly pushed for meetings with Thomas’ clients and told him to take a backseat, according to Thomas, who added that when he refused, Gleason told him not to attend board meetings, even though Thomas was vice chair. And in multiple phone calls, he said, Gleason threatened to withhold some $5 million in accrued benefits, including stock options, owed to him if he didn’t fall in line.

“The way I could protect that money is if I chose to take a different role: to discuss with my clients that I was tired and burnt out and to actually make introductions of those clients to George during my remaining tenure with the bank,” Thomas said. “And that obviously was not acceptable.”

“While you hate to lose any important, high-performing individual from your company, the fact of the matter is, we got a very deep team there,” Gleason said when Thomas’ exit was announced. “I don’t expect it to have a significant impact on our volume.” He did not comment publicly on the reason for Thomas’ departure, but according to one analyst, Gleason did indicate that Thomas was “burned out.”

Bank OZK rebuts Thomas’ account. “Many of the statements you attribute to Mr. Thomas are inaccurate or untrue,” it said in a statement to TRD. “Mr. Thomas voluntarily resigned.”

With the rainmaker gone, Gleason told investors he would spend 75 percent of his time overseeing the team in Dallas and keep the real estate deals flowing. But three current and former employees disputed this in interviews, including one who said Gleason “probably shows up once a month, for two to three days at a time.”

Gleason’s absence isn’t the only issue dogging the lending group. Current and former executives are facing allegations of sexual misconduct and age discrimination, according to an ongoing lawsuit in U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas. The plaintiff, Anna Carrillo, who led the loan closing division, claims she was fired in October 2017 days after complaining that a junior paralegal in the department was underperforming. That paralegal, Carrillo alleges, was being protected because she was engaged in an inappropriate sexual relationship with another executive in the group, Wes Hardin. The bank has denied all allegations in the suit.

Carrillo, who is 54 and oversaw the closing of over 250 transactions, claimed that while the company framed her termination in October 2017 as part of a “restructuring,” many of her duties were assigned to the paralegal, who is in her 20s. (See sidebar for more on the complaint.)

Carrillo, who is 54 and oversaw the closing of over 250 transactions, claimed that while the company framed her termination in October 2017 as part of a “restructuring,” many of her duties were assigned to the paralegal, who is in her 20s. (See sidebar for more on the complaint.)

Fault lines

Last year, the bank underwent a multimillion-dollar rebranding as Bank OZK, a move it said would free it from “the limitations of a name tied to a specific geographic region.” But with its new name and under the new leadership at the real estate lending group, the bank has struggled to keep up its rapid growth.

Between the second quarter of 2015 and the second quarter of 2017, construction lending at the bank grew 180 percent to $5.5 billion. But in the second quarter of 2019, construction lending totaled $6.6 billion, just a 20 percent increase over a two-year period.

Gleason has said this is in part because there are fewer deals available and more competition from debt funds and other alternative lenders.

“Our lenders are doing a very good job of generating positive loan growth in a crazy, competitive environment,” Gleason said on the July 19 earnings call. “Our new originations in New York are not as large as they were a year ago — there’s less new product being created.”

But current and former employees in the bank’s real estate group said that part of this drop is due to a decline in big-ticket business with the largest players, including Brookfield Property Partners, Blackstone Group and Starwood. Those firms did not return a request for comment.

Bank OZK’s slowing growth comes amid a drop in activity in its primary markets. In Miami, the bank’s second-largest market, there were only four groundbreakings for condo projects in 2018 amid an estimated six-year oversupply of luxury condos, according to the consulting firm Condo Vultures.

A slump in the real estate market would impact Bank OZK more than most of its rivals because commercial real estate loans represent more than three-quarters of its loan portfolio, according to its 2018 annual report. The bank could face pressure to finance more questionable deals.

“Construction lending is a high-risk business; it tends to do well when the economy is doing well and tends to be painful during a recession,” said Raj Singh, the CEO of BankUnited, which has branches in New York and South Florida. “If there is a bump in the road, [Bank OZK] will feel it.”

But believers in the bank say concerns about its health are unfounded. Stern noted that the bank provided only 38 percent of the total $135 million loan at his 9 DeKalb Avenue, a leverage point that would shield it from default.

“There is a perception that they take more risk than they do,” he said. “That’s a complete misunderstanding. You are looking at their financial health in a vacuum.”

Even so, Bank OZK last year wrote off two loans made a decade ago by a total of $46 million, prompting its stock price to drop 24 percent. Another loan in California could be written off in the future. And this year in Manhattan, it was forced to reduce a $108 million loan to Xinyuan Real Estate by $20 million after the Chinese developer dismantled its local team, hit multiple delays on the project and brought on another firm to oversee its developments.

Those disclosures have come in the two years since the bank stopped filing annual reports to the SEC. And under its new primary federal regulator, the FDIC, the bank has acknowledged that its construction lending activity relative to its capital levels far exceeds the agency’s guidelines.

Hicks, Bank OZK’s chief administrative officer, said the bank has processes in place to keep that lending in check.

“We’ve been above the guidelines for 12 years,” he said. “And as I mentioned before, they are guidelines.”

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that the state of Arkansas required banks to keep their holding companies.

—Ashley McHugh-Chiappone contributed research.