Stellar Management has kept a notably low profile for most of its roughly 35-year existence, especially compared to some other New York landlords like Blackstone, LeFrak and the Related Companies. But the investment and management firm has become increasingly hard to ignore.

The company has its hands in everything from the multifamily market to ground-up development to Opportunity Zones.

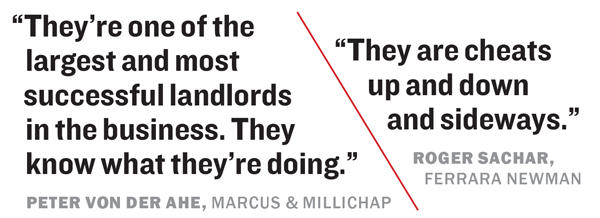

But views on Stellar vary widely — to the point that the one company can sound like two entirely different firms, depending on who you’re talking to.

To its industry peers, Stellar is a well-managed landlord that’s successfully navigated New York’s constantly changing real estate landscape while maintaining good relationships with its business partners.

“I have always found them to be on the cutting edge of creativity,” said Mitch Konsker, a JLL vice chair. “They have always dealt with the brokerage community in the most professional manner.”

But tenants’ groups and housing advocates have an entirely different take. They consider the firm one of the city’s most egregious violators of rent regulations and have made it a frequent legal target over the years.

“They are cheats up and down and sideways,” said Roger Sachar, an attorney at the law firm Newman Ferrara who’s representing tenants in a class-action lawsuit against Stellar that accuses the company of multiple rent-law infractions.

One thing both sides acknowledge: Stellar is as busy as ever.

The company — which owns about 100 multifamily buildings across 12 million square feet in New York City, as well as more than 2 million square feet of office space — is continuing to aggressively build and invest in new properties. And the firm hasn’t slowed down in the face of changes to New York’s new rent law.

It recently announced plans to construct a new office and retail building in Astoria. That’s in addition to its new two-building office redevelopment dubbed One Soho Square — which it refinanced with a $900 million five-year CMBS loan from Goldman Sachs in May — and the nearly 200-unit rental OTTO Greenpoint that it recently developed at 211 McGuinness Boulevard in Brooklyn.

It recently announced plans to construct a new office and retail building in Astoria. That’s in addition to its new two-building office redevelopment dubbed One Soho Square — which it refinanced with a $900 million five-year CMBS loan from Goldman Sachs in May — and the nearly 200-unit rental OTTO Greenpoint that it recently developed at 211 McGuinness Boulevard in Brooklyn.

The company has more than 600 employees, and several sources say that co-founder Larry Gluck — who is in his mid-60s — has largely stepped away from day-to-day business due to health issues but still signs off on major business decisions. (Several sources explained his health issues more specifically, but since the firm did not confirm it, TRD is not including it.)

A spokeswoman for Stellar said that Gluck “is still actively involved in the company, including the day-to-day operations and larger strategy.”

Either way, principal and chief operating officer Adam Roman, along with principal and chief investment officer Matthew Lembo — who joined the firm in 2008 after a three-year stint at Cushman & Wakefield — are very much involved and have both assumed more responsibility in running the company, sources say.

And competitors say the firm very much has its foot on the gas.

Steven Vegh, president of the multifamily sales brokerage Westwood Realty Associates, said Stellar is not one to let the political environment stop it from doing new deals.

“Stellar is a company that will find new opportunities in any market,” he said.

Opportunistic plays

One area the company is doubling down on is Opportunity Zones, the federal program that gives developers tax breaks and deferments in exchange for investments in what are supposed to be struggling areas.

Stellar is partnering with AKI Development on a planned 55,000-square-foot, 10-story mixed-use building — including office, retail and community space — at 35-01 36th Avenue in a designated OZ in Astoria. The duo bought the site for $5 million in October.

But unlike many other real estate players — Brookfield, RXR Realty and Silverstein Properties, to name a few — Stellar is not raising outside capital for its OZ investments. Instead, the firm will deploy money it already has on hand.

But Stellar took an unusually strong interest in trying to impact which census tracts in the city landed these controversial OZ designations, according to multiple developers and documents TRD obtained through a Freedom of Information Law request.

In April 2018, for example, the company contacted the Empire State Development Corporation — one of the government entities helping oversee the program — with detailed suggestions about census tracts to include. It also noted that it was “ready and willing to swiftly deploy at least $100 million of equity capital” into those areas.

Some of Stellar’s suggestions were for areas not generally considered low-income, including a roughly 16-block tract on Manhattan’s Far West Side between West 50th and 58th streets.

“The list that we have put forth simply represents crucial census tracts to this program, which, if nominated, we believe will receive widespread and immediate investment,” Stellar’s Lembo wrote to ESD Regional Director Joseph Tazewell in an email.

RXR President Michael Maturo, whose company launched its own $500 million OZ fund last year, said it was strange for a developer to push aggressively to ensure that certain areas received the OZ designation.

“I don’t think that’s how the program was intended,” Maturo said. “I haven’t heard of anybody doing that, so it strikes me as odd just on that basis.”

The state ultimately bestowed the OZ designation on the Far West Side, but officials told TRD it had been part of its plans for years and that Stellar’s recommendation did not play a role in the decision.

ESD spokesperson Kristin Devoe said the state “worked within federal guidelines,” which included factoring in guidance from the state’s Regional Economic Development Councils as well as gathering local and public input.

“This was a data-rich, regionally focused process, and all nominated tracts were subject to federal approval,” she said in a statement.

Stellar’s other OZ recommendations included tracts in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Washington Heights, Bushwick and the area surrounding Penn Station as well as on the Lower East Side.

“While Opportunity Zone regulations do provide tax benefits, they also bring permanent jobs and increased commerce to designated neighborhoods,” Roman said about the firm’s interest in the program.

Who’s the boss?

Stellar Management has been active in New York since Gluck and developer Steve Witkoff founded the firm in 1985.

The name Stellar came from combining the first three letters of Steve and Larry — with an extra “L” thrown for good measure (and accurate spelling) — as the firm focused on buying and building low-income rental properties in Washington Heights.

Witkoff — who left the firm in 1997 to launch his namesake Witkoff Group — declined to comment apart from describing Gluck as a friend he greatly respects.

While several sources acknowledged Gluck’s health issues, one broker familiar with the company, who asked not to be named, said: “I don’t think he has missed a beat on what questions he asks, what he looks for.”

Cushman’s Doug Harmon described Gluck as still “thriving” and “hungry” in today’s market.

“I have for many years bet on Larry Gluck,” Harmon said. “He is a perennial favorite to win in most New York City offerings he sets his sights on.”

There has, however, been some internal rejiggering recently.

Former co-owner Paula Katz no longer works there, a spokesperson for the firm confirmed. Katz — who had been with the company since its founding — stepped back about a year ago, but she remains a minority partner in many of its investments.

She and Gluck worked together at the law firm Dreyer & Traub and then struck out on their own to create Gluck & Katz, which later became Stellar’s legal arm.

Stellar’s recently opened, nearly 200-unit OTTO Greenpoint

Greenberg Traurig’s Robert Ivanhoe, chair of the global real estate practice — who overlapped with Katz, Gluck and Witkoff at Dreyer & Traub — said Lembo and Roman have both stepped up at Stellar recently.

And within roughly the past year, the firm bought a 32-unit apartment building on Bedford Avenue in Williamsburg for $12 million and sold its Highbridge House rental building on Ogden Avenue in the Bronx for $76 million.

Roman said the firm’s investment strategy of “maintaining a diverse portfolio” remains the same under the new rent regulations.

At One Soho Square, where it’s partnering with Imperium Capital, it has signed on Warby Parker and Trader Joe’s. And this spring it locked in its largest office lease there — a 10-year, roughly 122,000-square-foot expansion with Flatiron Health that brings the healthcare tech firm’s total footprint in the building to more than 220,000 square feet.

Marcus & Millichap’s Peter Von Der Ahe said even if Stellar could no longer rely on the multifamily space as much, its muscle would allow it to pivot.

“They can move fast if they like something,” he said. “They’re one of the largest and most successful landlords in the business. They know what they’re doing.”

Legal matters

Despite the praise Stellar gets from some in the industry, it has been embroiled in several lawsuits over the past few years.

Multiple tenants and attorneys have accused it of exaggerating the amount — and cost — of work it’s done under the state’s Individual Apartment Improvement program to justify destabilizing rental units. And those accusations are now colliding with the state’s new rent law, which has put greater restrictions on the use of IAIs to flip units to market rate.

“What we’ve seen through prior cases is that they have a pattern and practice of pretending that they did a whole bunch of work that would justify deregulation,” said Jennifer Rozen, an attorney representing a group of tenants at 50 West 97th Street who accuse the landlord of wrongfully deregulating apartments. “They falsify documents and itemize work that’s never been done.”

The tenants — who are demanding money to make up for years of what they say are excessive rent payments — found that Stellar would have had to spend an “astronomical” amount to justify the deregulation when going through rent histories at the building, Rozen said.

Justin Hebenstreit, the lead plaintiff in the lawsuit, said he requested his apartment’s rent history and found out that the unit was going for just $385 per month about 10 years ago. Stellar, he said, would have needed to do about $60,000 worth of work to get it out of rent stabilization.

“Immediately, that got me pretty skeptical that they had done that,” he said, “especially given their recent track record.”

Hebenstreit added that his main concern is Stellar’s alleged rent-law violations. Outside of that and some occasional building issues, he said the company has been a good landlord.

Stellar has filed a motion to dismiss the case and remove it to the state’s Division of Housing and Community Renewal, but the judge has yet to rule on that, according to Rozen.

Housing Court Judge Sabrina Kraus ruled in favor of the tenants in a similar case this year at Stellar’s 171 West 81st Street. She found that the company gave the impression it had paid a contractor $71,000 to make IAI improvements, despite actually using an in-house employee to do the work. Her decision required Stellar to pay tenants more than $123,000 in damages.

Meanwhile, almost 60 tenants are joining forces in a class-action suit against the firm at buildings throughout the city, claiming Stellar misrepresented IAI costs and received J-51 tax breaks that it was not entitled to. (Landing those tax abatements requires landlords to provide their tenants with rent-stabilized leases.)

“Their IAIs are so bad and so lacking,” said Sachar, one of the attorneys spearheading the case. “They were operating as if the rent laws were never going to apply to them.”

Attorney Lucas Ferrara, who is working with Sachar on the case, echoed that point and said Stellar’s alleged violations were “the most extreme examples of sidestepping the rent laws that I’ve seen in 30 years.”

Stellar declined to comment on the lawsuits, noting that they are ongoing legal matters.

Meanwhile, back in 2017 — before the rent law was passed — former Stellar investor Rob Rosania claimed Gluck had made secret arrangements with contractors doing work in Upper West Side buildings as part of a scheme to inflate the prices charged for renovations.

Rosania said apartment improvements were jacked up by $40,000 in two buildings he invested in, allowing Stellar to charge an extra $667 per month per unit.

The case was settled under confidential terms, according to Stellar. Rosania’s attorneys declined to comment.

New realities

The new rent reforms include dramatic limits on the IAI program, capping the total renovation cost at $15,000 over a 15-year period.

Ferrara said Stellar and other landlords are still refusing to accept that they have to operate under these new rules.

“They’re still in denial,” he said. “They all think there’s some white knight that is going to save them from these terrible rent laws, and it isn’t happening.”

Greenberg Traurig’s Ivanhoe maintained that Stellar is unlikely to dramatically alter its business plan in the face of the new law.

“If they wanted to get out of stabilized properties, they’d be selling, and Larry is not the kind of person who, just in general, is a seller,” he said. “He’s just not a seller, and he believes once he buys something, make it better, improve it, get the property performing better, looking better, and then hold onto it forever.”

“That’s just kind of his general philosophy,” Ivanhoe added. “So if he has to deal with the new rent laws, I think he’s just going to deal with the rent laws the best he can.”