It’s been a sort of parlor game in New York’s real estate community for some time: speculating on whether peak-market buyers will hold on to their highly leveraged properties.

Then, in a move that shook the industry last month, Tishman Speyer Properties and BlackRock Realty decided to turn over the keys to the $5.4 billion Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village.

But not everyone has gone this route. Other overextended borrowers have kept control of their properties following a debt restructuring, including developers Lev Leviev and Joseph Moinian.

As part of a workout — the complex process that’s often decided by the leverage each party has in the development — the bank or private equity firm must weigh its options. The choices generally include walking away, taking pennies on the dollar, foreclosing or even lending more and staying put.

“Lenders will often consider loan extensions and modifications when the borrower is willing to invest new capital, which will add value to the collateral,” said Steven Kohn, president of financial advisors Cushman & Wakefield Sonnenblick Goldman.

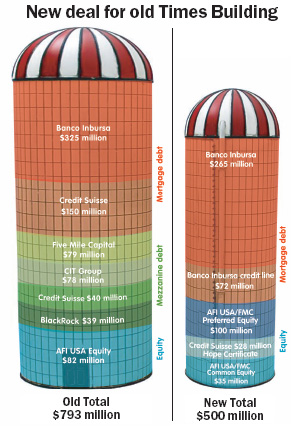

The Real Dealtook an exclusive look at how the debt was restructured in the largest of the completed deals: the former New York Times Building at 229 West 43rd Street. The building, purchased by Leviev’s Africa Israel Group in 2007, just recently cut its debt by more than half to $337 million.

The CEO of Africa Israel USA, as well as an anonymous source close to the deal, explained the restructuring with new details, including how $386 million in mezzanine and subordinate debt was retired with $30 million and a possible share in a future sale of the building, known as a hope certificate.

The case could be an important model for other workouts in the city.

Mexico trip secures millions

The central problem Africa Israel had with the New York Times Building was simple but painful. Purchased in June 2007 for $525 million, the 750,000-square-foot building was, because of the downturn, suddenly worth far less than the $793 million that had been invested in it through debt and equity since then, Africa Israel USA CEO Richard Marin said in an interview.

So much so that by December 2008, the economic downturn led Africa Israel, a public company based in Israel, to report the building’s value at only $315 million, court documents showed. And a subsequent Cushman & Wakefield analysis valued it even lower, at $220 million, Marin said.

Marin, a former CEO of Bear Stearns asset management, said a counterintuitive feature of the restructuring was that its extremely low valuation as an office building made it easier to restructure the debt.

Instead, Africa Israel decided last year to abandon the office building plan, double the retail space and add a hotel and condos. Under that new development plan, with about half the retail space already leased, the source said the building is now valued at about $500 million.

“There is a funny schizophrenia in it, because on the one hand you have to say how bad this is as an office building, and on the other hand you have to say how great this could be,” Marin said.

To hold on to the building, Africa Israel needed to get the support of the senior lender, Banco Inbursa, because with the loan in default and so severely underwater, it could foreclose and wipe out Africa Israel and all the other junior lenders.

Marin traveled to Mexico City, where he secured the support of the bank, which is owned by one of the world’s richest men, billionaire Carlos Slim Helu, for the new plan. He left Mexico with a pledge from Banco Inbursa that it would provide more than $70 million in a revolving line of credit, slightly increasing its exposure by $13 million to $337 million.

New money equals power

But winning the backing of the top lender was just a start. The four subordinate lenders, who owed a combined $386 million, needed to be satisfied as well. While the low valuation on the building suggested that their investments were now worthless, they still had the ability to gum up the process with lawsuits.

In fact, in July 2009 mezzanine lender Five Mile Capital sued, alleging Banco Inbursa and Africa Israel were working out a secret deal to cut the debt and squeeze out the junior lenders.

Marin said that as they negotiated a reworking of the debt, the players used their financial and legal rights as bargaining chips. “The art of doing a restructuring like this is understanding everybody’s agenda — in the context of your legal situation and the context of your economic situation — and it makes a difference who in that capital stack has money and who doesn’t have money. Who in that capital stack has a sense of urgency and who will sit until the end of their lives if they have to,” Marin said.

As part of the deal, Five Mile joined with Africa Israel, and paid the other mezzanine lenders, CIT Group, BlackRock and Credit Suisse, a total of about $30 million to relinquish $157 million in mezzanine loans and a $150 million subordinate portion of the mortgage debt held by Credit Suisse, a source close to the deal said. Credit Suisse also received a hope certificate valued at $28 million, the source said.

The deal source said CIT Group, under pressure in bankruptcy proceedings, was not in a position to invest more money in the project.

And Five Mile Capital, instead of taking a payout of pennies on the dollar, converted its $79 million mezzanine loan — and paid a smaller portion of the $30 million in new equity — for a 50 percent ownership through common and preferred equity with Africa Israel.

It was fortuitous that Five Mile had unspent dollars available in the fund that made the initial investment in the building to make the new payments, as several experts said it would be unusual to use money from one fund to support an investment from another fund.

“You could be looked at as trying to bail your own investment out in the first fund … but I don’t know, everybody is a little bit different,” said Jonathan Estreich, a founding partner of investment firm RCG Longview, who was not involved in the deal.

“New money is what has the power,” Marin said.

Predicting the next restructuring along these lines isn’t easy, but there’s at least one incentive for lenders.

James Houlihan, a sales broker and partner with commercial firm Houlihan-Parnes Realtors, said lenders are wary of taking back properties.

“There is no guarantee if they take it over … it increases in value. And with the wrong ownership it could lose value,” he said.