Rather like the fabled (and fabulous) 15 Central Park West, but designed for a somewhat different clientele, Annabelle Selldorf’s 200 Eleventh Avenue has assumed a nearly mythic stature among those happy souls who take an almost libidinous interest in Manhattan real estate. Even before its completion, its soaring ceilings, its varied amenities and its location in Chelsea, overlooking the Hudson River, made it seem like some fantastic apparition to the majority of New Yorkers, who could only look into its massive windows in amazement.

Few instances of conspicuous consumption have so caught the imagination of New Yorkers in recent years as the fact that this new project, developed by Gaia House, a partnership of YoungWoo & Associates and Urban Muse, includes something called an “en suite sky garage.” Apparently the idea is to liberate the inhabitants of the building from having to deposit their car in a basement garage or — oh, the horror! — parking it on the street. Instead, the car enters a dedicated elevator and rises with you to your floor. And as if that weren’t fabulous enough, it has been reported in The Real Deal that Domenico Dolce, of Dolce and Gabbana fame, has bought two penthouse apartments in the building and that one of his neighbors is Nicole Kidman. The project is expected to be completed in the next few months.

This building, however, is only the latest in a series of high-profile projects with which the German-born Selldorf has been associated over the past few years. She is, for example, a member of that very select club of architects whose creations have recently forgathered at 19th Street between 10th and 11th avenues: Frank Gehry’s the Sails, which stands on 11th Avenue, directly across the street from Jean Nouvel’s nearly completed 100 Eleventh; just to the east of the Sails is Shigeru Ban’s Metal Shutter House; and, next to that, Selldorf’s own 520 West Chelsea.

But no one, of late, has been more consistently associated with this part of Manhattan than Selldorf herself. She played a major role in the design of what is still being called Philip Johnson’s Urban Glass House, about ten blocks south on Hudson Street (even though the degree of his authorship is by no means certain); the Gladstone Gallery at 515 West 24th Street (not to mention galleries for Michael Werner and David Zwirner); and now 200 Eleventh Avenue. That’s not to mention numerous interiors that she has designed in this part of the city.

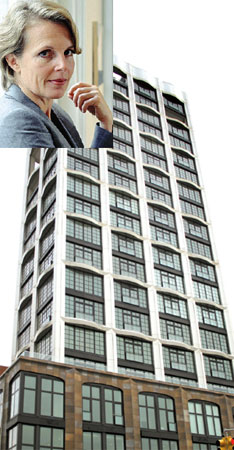

200 Eleventh Avenue and architect Annabelle Selldorf

Put all of these projects together and there emerges a sort of undogmatic pluralism to Selldorf’s approach to design. Indeed, she designed Ron Lauder’s Neue Galerie on 86th Street and Fifth Avenue, which, with its sumptuous Beaux Arts aesthetic, feels as though it were a world away, both in spirit and in formal terms, from what she has accomplished more recently in Chelsea. If I had to hazard a generalization about Selldorf’s designs, however, I would say they are characterized by a tentative historicism, which certainly distinguishes Selldorf Architects’ contribution on West 19th Street from the hardcore modernism of Shigeru Ban, and the Deconstructivist style of Frank Gehry and Jean Nouvel. That is to say that Selldorf tends to favor a gridlike structure over which she spins textured surfaces which — both in their materials and in their vocabulary — recall an earlier age. And so, at 520 West Chelsea, she has recreated a grid of ribbon windows, sharply defined along their horizontal axis, which suggests the early Modernist functionalism of the 1930s, with a nod to the lofts and factories that once defined much of this part of Manhattan.

At 200 Eleventh Avenue, however, Selldorf has changed her aesthetic again. There is an improvised quality to the building’s design, a pluralistic amalgam of motifs. Although some of the motifs along the surface look slightly familiar within the context of Postmodern contextualism, they have in fact no canonical authority, within either the context of Modernism or of Postmodernism. Properly understood in this connection, 200 Eleventh Avenue is one of the strangest buildings to rise in Manhattan in some years: That is, it is far stranger than all those gooey, molting, mutating and collapsing Deconstructivist structures that have so noisily sought to define New York starchitecture over the past decade.

What makes this building so strange is that it is trying to appear centered, and even perhaps a little conservative, and yet so many things have been thrown into the design that the result seems to owe as much to a series of coin tosses as to any premeditated plan.

The first three floors, with lofty ceilings, are clad in cast gunmetal-glazed terra-cotta. Above these, on one side, are prolonged passages of nearly unrelieved concrete, while the front façade, facing the Hudson, is whipped up into a sculptural froth of stainless steel, hand-cast (according to the building’s website) by A. Zahner Company. The result is hardly an eyesore, but it does seem somewhat less distinguished than one might have wished for from this renowned architect. And once you start to pay closer attention, its many arbitrary inconsistencies — like the wayward shift from textured to flattened surfaces — feel like an affront to formal logic.

The late art historian Michael Baxandall famously spoke about the “period eye,” the way in which one generation of humanity saw reality, in opposition to all earlier and later generations. Well, apparently many of our contemporaries will pay exorbitant sums to find beauty by looking out the windows of 200 Eleventh Avenue. As for the rest of us, I am not sure that we will find much of it by looking in.

At least in her residential work in Manhattan to date, the results are not yet sufficiently accomplished to justify the exalted reputation that Selldorf enjoys among admirers of contemporary architecture.