SL Green CEO Marc Holliday

Real estate downturn? Don’t tell SL Green. The New York-based real estate investment trust has been wheeling and dealing like it’s 2007. Since December, the company has done roughly $1 billion worth of deals on property and debt in New York.

It’s a dramatic turnaround for a company that analysts were warning was in trouble just a year ago. Back then the company’s stock had plummeted from a high of $101 in 2008 to just $19 at the end of April. Many warned that its anchor tenant at 388 and 390 Greenwich — Citigroup — was likely to go under, while lease rates continue to drop around the city.

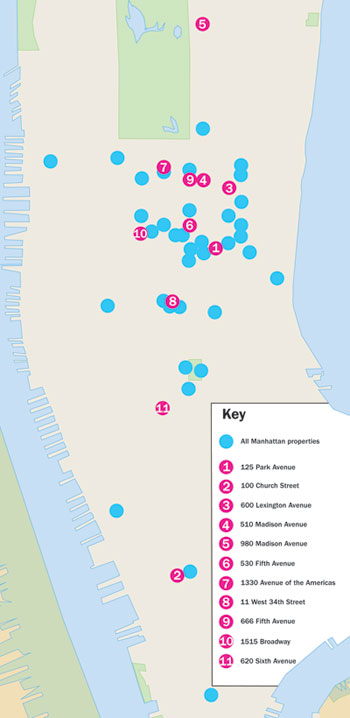

By last month, though, the REIT’s stock had tripled, and it was on the offensive, snapping up 125 Park Avenue at 42nd Street for $330 million, and announcing the sale of a 45 percent stake in 1221 Avenue of the Americans, the McGraw-Hill building, for $576 million. Part of those proceeds are earmarked for future investments.

The transactions come just a few weeks after the company agreed to shell out $193 million for 600 Lexington Avenue. It later sold a 45 percent stake in the property to a Canadian pension fund.

Perhaps more telling, though, is the firm’s willingness to buy up debt and go after desirable properties like Harry Macklowe’s 510 Madison and the Sapir Organization’s 100 Church Street.

By acquiring the debt on those properties, foreclosing, and then defending its actions in court — both Macklowe and Sapir sued — SL Green sent a strong signal that it has confidence the market has bottomed and the properties it’s going after are worth brawling over.

SL Green, which owns 30 properties totaling over 22 million square feet in New York, has operated a separate lending business for 10 years. And representatives of the company steadfastly maintain they only foreclose as a last resort. They wouldn’t comment on 510 Madison, and 100 Church is the only property they have foreclosed on in recent years, they said.

Still, many observers have labeled the Macklowe and Sapir acquisitions as textbook “loan-to-own” gambits — buying up bad debt, forcing foreclosure and taking possession of a trophy property on the cheap.

And even if loan-to-own is not SL Green’s primary goal when acquiring debt, these two cases provide a preview of the fierce battles that can be expected in the coming months, as opportunity funds and other REITs use some of the “dry powder” they’ve been collecting to get bargains any way they can.

“We’ll probably see quite a few [loan-to-own acquisitions] this year,” said Kevin O’Shea, the managing partner of law firm Allen & Overy’s New York office.

O’Shea represented the entities that wrested control of two other trophy towers from their owners in loan-to-own purchases in recent months: Sheffield57 in Manhattan, and the John Hancock Tower in Boston. “About $1.4 trillion of debt is going to be maturing between now and 2012,” he said.

Going on offense

SL Green will be in a good position to buy up some of that debt.

After REIT stocks plummeted about a year ago, restructuring balance sheets became “a question of survival” for SL Green and other REITs, said Hans Nordby, chief strategist at the CoStar Group.

“[REITs] are ahead of the private sector in deleveraging, because they had to be,” Nordby said. “They went out and took their medicine. As a result, many have gone on the offensive. It’s a pretty dramatic turnaround.”

For its part, SL Green has raised between $750 and $800 million since last May, through equity issues and other means. In addition, the firm refinanced $1 billion worth of mortgages on properties it owns, in some cases borrowing at lower rates for higher amounts and taking cash out of their properties. Those actions allowed them to “term out,” or spread out their liabilities on their balance sheet, pay down debt and stockpile capital to go shopping, said Andrew Mathias, SL Green’s president and chief investment officer.

The company began looking for opportunities around December 2009, Mathias said. By the fourth quarter of 2009, he noted, leasing activity had more than doubled from the prior six-month average, with more than a million feet leasing every month in Manhattan.

“As the largest owner of office space in Manhattan, we are able to see with a little bit better visibility than some other market players,” Mathias told The Real Deal during an interview last month at the company’s Midtown office. “We can get a pretty good bead on exactly what the trend is in Manhattan. We came to the conclusion that leasing had likely bottomed and that rental declines were pretty much stopped. And we switched back into acquisitions mode.”

It wasn’t until recently, however, that sellers decided the market had stabilized enough for them to test the waters. So initially, opportunities were scarce.

SL Green’s first acquisition since deciding the market had bottomed was an opportunistic play. It bought a construction mortgage on the 30-story glass tower built by Macklowe at 510 Madison. It paid $170 million for the $267.5 million senior mortgage from the original lender, Union Labor Life Insurance Company, and later acquired a senior mezzanine loan for less than $15 million.

Although foreclosure was not the company’s stated intention when it made the purchase late last year, few observers expected SL Green to simply collect the interest on the Macklowes’ tower. Many noted that in order to generate a significant profit on its investment, it would have to gain possession of the building. The New York Times noted at the time that the buy “suggests that the company is prepared to engage in a bare-knuckles battle with Harry Macklowe, one of the city’s most litigious property owners.”

And that’s exactly what happened. SL Green called in an appraiser, declared the Macklowes underwater and attempted to foreclose. Macklowe sued in state Supreme Court, accusing the company of reneging on prior agreements to extend construction deadlines, and failing to take into account delays caused by a 2009 fire at the property. The case is currently being litigated.

Both SL Green and the Macklowes declined comment.

At the time of the Macklowe buy, SL Green was already showing willingness to play hardball with a number of other distressed property owners.

Also in December 2009, it used its position as holder of $30 million of subordinated mezzanine debt to begin foreclosure proceedings on 620 Avenue of the Americas, a 700,000-square-foot building owned by Yair Levy, Meyer Chetrit and Charles Dayan. Eventually, SL Green agreed to drop the proceedings in exchange for an aggressive capital injection from the owners.

Meanwhile, SL Green was already in the process of assuming the ownership of a 1.1 million-square-foot office tower at 100 Church Street, owned by the Sapir Organization. SL Green had purchased three mezzanine loans for that building, located near Ground Zero, for $41 million in 2007, and seized the building when Sapir failed to meet certain income thresholds required by those loan agreements.

The Sapir Organization filed a suit to block foreclosure, alleging SL Green prevented it from signing leases on the building that would have allowed it to extend its loans. Eventually, however, Sapir withdrew the suit and SL Green emerged with possession. Last month, it signed a 20-year lease for nearly 22,000 square feet of space with the Farber Center for Radiation Oncology.

Downplaying loan-to-own

During an SL Green earnings conference call with analysts in April, CEO Marc Holliday declined to comment on the Macklowe case, dismissed the 100 Church foreclosure as an anomaly, and took pains to downplay any future plans of loan-to-own.

“We have done billions and billions of this kind of originations; we have had one foreclosure and that is 100 Church,” Holliday said. “The vast majority of what we originate… [is] going to be loans that we expect will either fully perform, will be restructured for performance, or that we may sell if we get a good bid. Rarely are they going to result in a foreclosure.”

But the fact that Holliday was even asked about the loan-to-own issue by analysts is telling. And observers say acquiring distressed debt does, in fact, play to SL Green’s strengths.

The company already dabbles in subordinate mezzanine loans, which “by its very nature is a more entrepreneurial investment and is not for the faint of heart,” said Robert Freedman, chairman of Colliers International. The willingness to foreclose is a key exit strategy for any mezz debt holder, the benefits and costs of which are included in the calculus of any deal, he said.

Pursuing a loan-to-own strategy requires significant in-house expertise and a willingness to spend money on legal fees, which SL Green has clearly demonstrated it has and is willing to use.

“There is a lot of legal work around this kind of strategy,” said Craig Gutterplan, an analyst at CreditSights who covers SL Green. “There’s a lot of red tape.”

Loan-to-own “is a common form of real estate investment, and it’s definitely picking up momentum right now,” Gutterplan said. “It’s really the debt holders who are at the steering wheel. They have the power to wrestle the property away. A lot of banks don’t want the property, so they have a different interest than a hedge fund or a private equity fund, or maybe an SL Green, who does want to get the property.”

But so far, only a handful of loan-to-own cases have actually come to fruition in New York.

Among those cited by industry observers who declined to be identified: Rockpoint, a private equity firm, acquired the debt and appears poised to execute a loan-to-own strategy on Park Central Hotel and the Hotel Lexington.

Allen & Overy’s O’Shea has been at the center of two of the most high-profile loan-to-own battles in recent months. He represented Fortress Investment Group, the Manhattan-based investment fund, which successfully wrestled control of the Sheffiled57 from developer Kent Swig last August. The company reportedly acquired $32 million in senior mortgages and a $72 million senior mezzanine loan at an undisclosed discount, then acquired the entire project for just $20 million at a foreclosure sale (O’Shea would not confirm the numbers).

O’Shea also represented Normandy Real Estate Partners, the New Jersey-based private equity firm that bought a $725 million mezzanine loan for an undisclosed sum from Lehman Brothers and RBS in March 2009. The debt was secured by seven properties owned by Broadway Partners. In the end, Broadway paid off the debts on five of the properties. Normandy foreclosed on and won possession of the other two: Boston’s John Hancock Tower and 10 Universal City Plaza outside Los Angeles.

Though O’Shea wouldn’t reveal the specific finances of the Hancock or Sheffield57 deals, he offered an overview of how a typical loan-to-own deal unfolds.

For instance, if a borrower on a building defaults on any of the loans in the capital stack, no matter how junior, the entity holding that loan can foreclose under the Uniform Commercial Code. The key for any investor looking to step in is to identify what is known as “the fulcrum loan,” O’Shea said.

If, for example, the capital stack on a $100 million building consists of a $50 million first mortgage, a $20 million first mezzanine loan, a $20 million second mezzanine loan and $10 million in equity, when the building’s value falls to $65 million, the first mezzanine loan is the fulcrum loan. That’s because if the building were then sold, the top of the stack — the owner’s equity and the second mezzanine loan — would be wiped out, while the first mezzanine loan would retain some value.

If the debtor stops servicing the first mezzanine debt, the owner of that loan has the right to foreclose. When he does, he has a number of advantages over rival bidders, O’Shea said.

Even though the loan is worth only $5 million if the building were sold — and the investor might have paid just $2 million for it — in a foreclosure auction, the investor would receive a $20 million credit for the value of the original loan towards the purchase of the building. He could therefore bid $70 million for the $65 million building, but only have to pay $50 million to complete the sale.

In addition, many current mezzanine debt agreements have the right to purchase the senior debt in front of them — which is critically important in the current market, said O’Shea, because credit is so tight, and it would likely be extremely difficult to replace a $50 million loan by borrowing.

“There are a number of other deals around the country, where people are currently executing this type of strategy,” said O’Shea, who expects to see at least 20 to 30 such scenarios play out in the next year alone.

Active pipeline

Whether SL Green decides to engage in future loan-to-own strategies or not, its recent building buys will likely affect the calculus of others dabbling in this specialized field, O’Shea said.

SL Green purchased 600 Lexington for $636 a square foot, a premium that surprised some observers. That will raise the valuation of some of the underwater properties, and change which loan in the capital stack investors consider the “fulcrum loan,” O’Shea said.

Isaac Zion, an SL Green managing director who oversees property acquisitions, said the company believes it got good value for its money. Even at $636 a square foot, the cost of the building was still about 40 percent below replacement costs. He added that lease rollover in the next two to three years will allow it to increase income as lease rates rise.

“This is a building that easily would have traded for over $1,000 a square foot when the market was at its peak,” Zion noted. “The window of opportunity” for buying quality office buildings “has opened, and we would rather be the first movers than the last movers,” he said.

The tower SL Green acquired at 125 Park was available at about 50 percent below replacement costs, Zion said. The building is approximately 99 percent leased, and contains about $35 million in recent upgrades.

The kinds of properties now entering the market have “definitely changed in the last few months,” Zion said. “It’s only now that you have straightforward real estate deals getting done.”

David Schonbraun, an SL Green managing director, said the company has also been busy on the debt front. They bought bonds and other assets in recent months attached to 980 Madison, and acquired a B note on 530 Fifth Avenue where they already own mezzanine debt.

And SL Green is not the only firm buying.

Among the other recent deals: 417 Fifth Avenue, an 11-story tower sold to Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim Helu for $140 million from Joseph Moinian, and 340 Madison, a 23-story office tower purchased by RXR Realty for $570 million from Broadway Partners.

Zion said a number of other properties are “about to hit the market.” Expect SL Green to be busy in the months ahead.