Since January, Glenwood Management has been ensnared in scandals involving two of the state’s top politicians. Though not charged with any wrongdoing, the firm has been thrust into a glaring spotlight. Yet sources say the company’s 100-year-old founder and chairman, Leonard Litwin, remains in the shadows.

Litwin, who founded Glenwood in 1961, no longer comes into the firm’s main Long Island office and has very little knowledge about the corruption cases, according to sources familiar with the situation. Executives at Glenwood have avoided discussing matters with him, so as to not upset him, sources said.

While Litwin and Glenwood — which owns 26 Manhattan buildings with roughly 8,700 residential units — have been the most prolific donors to politicians in New York State for more than a decade, until recently they’ve made their mark quietly. More than two-dozen LLCs affiliated with Glenwood and Litwin made the donations, though Litwin did not control the entities alone. Source said others at Glenwood make donations on his behalf.

The firm’s low profile, however, changed when it became clear that Glenwood was “Developer 1” in two blockbuster federal criminal complaints. Those complaints have, of course, taken down two of the state’s most powerful politicians: Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos, who both resigned their leadership positions after coming under fire.

In a nutshell, prosecutors outlined complicated schemes in which both politicians used their powerful roles as ATMs. Silver is accused of directing Glenwood to hire a real estate law firm run by a former aide, which then paid him handsomely for doing no work, while Skelos is charged with directing the developer to pay his son’s title insurance company $20,000 for work it did not do.

The developer allegedly complied with those requests in both cases. The complaint does not say what Glenwood was promised in exchange for hiring the law firm. It notes that, prior to being asked in 2012 to sign a retainer agreement, Glenwood did not know that Silver was getting 25 percent of all of the fees he directed to the firm. But the firm was lobbying for legislation, including 421a tax breaks — a major financial boon to developers.

While sources say Litwin stopped working in 2013, many of the events outlined in the Skelos complaint involving Glenwood occurred between 2010 and 2012.

For example, court documents note that Litwin and Glenwood general counsel Charles Dorego attended a REBNY event in 2011 and met with Gov. Andrew Cuomo and others prior to the vote on the Rent Act of 2011.

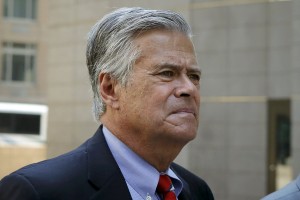

Dean Skelos

But Litwin has since stepped back.

“It’s become increasingly apparent that Mr. Litwin is not as out and about as in the past,” said developer Jeff Levine, who partnered with Glenwood on projects in the early 2000s.

Changing of the guard

Until June 2013, Litwin showed up at Glenwood’s New Hyde Park headquarters at least four days a week, sources said. But he’s since retreated to his Suffolk County home. (The home is not located in the Hamptons, in contrast to many top New York City real estate figures.) His wife Ruth, who reportedly suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, died in August.

The state of his health is unclear. “Old age is old age,” said a source close to Litwin.

The Litwin family also owns Woodbourne Cultural Nurseries in Melville, Long Island, though it’s unclear if Litwin, who according to Forbes had a net worth of $1.1 billion as of 2008, goes there either.

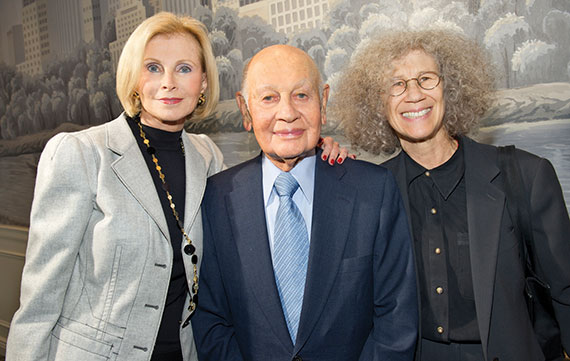

The firm is now being run by Litwin’s daughter Carole Litwin Pittelman, the company president, along with Jacob and Dorego.

Litwin, center, with daughter Carole Litwin Pittelman, right, and an unidentified woman on the far left. (Photo: Steve Friedman)

Dorego has reportedly been cooperating with prosecutors in the cases against Silver and Skelos.

But some sources told TRD that despite the fact that Glenwood has not been charged with any wrongdoing, they expect a changing of the guard at the firm, with longtime executives exiting. The question is whether that will happen before or after Litwin’s death.

“It’s hard to see how Charles Dorego could continue to function in his current job in New York, with everyone in the world thinking he was wearing a wire,” said John Kaehny, executive director of Reinvent Albany, a group that advocates for more government transparency.

Nevertheless, sources told TRD that Glenwood’s leadership has surprisingly carried on business as usual and held no company-wide meetings to discuss the Silver and Skelos cases. Glenwood referred requests for comment on the two cases to the firm’s attorneys, Alan Levine and William Schwartz of Cooley, who declined to comment on the matters.

Meanwhile, according to the New York Times, in exchange for his cooperation since April, federal prosecutors granted Dorego a “non-prosecution agreement.”

The agreement has not been publicly released, the Times said. Dorego’s lawyer, Kevin Downey of Williams & Connolly, did not return calls seeking comment.

But as one lobbyist told Capital New York: “If Dorego is involved, then you can bet more trees are going to fall.”

In the meantime, if the cases proceed to trial, Glenwood’s purported role will likely be laid bare.

“It’s not like Glenwood was wearing a white hat in a room full of black hats,” Kaehny said. “The whole real estate industry was actively lobbying for 421a and rent-regulation issues.”

Real estate players who talked to TRD said Dorego is well known and respected by his peers, and that he’s a regular at industry events.

Leonard Boxer (Photo: STUDIO SCRIVO)

Leonard Boxer, who heads law firm Stroock & Stroock & Lavan’s real estate practice, worked with Dorego at the law firm for about 14 years.

“Charlie was very congenial and smart when he worked for us,” Boxer said. “He was very close with people at Glenwood and that led to his next opportunity” as the firm’s general counsel. At the same time, the Times quoted an anonymous real estate executive as saying, “Charlie likes access. He likes to talk about access to politicians.”

Saving cash

Of Glenwood’s 26 New York properties, about a third received tax breaks and special financing under the 421a program, according to news reports and public records.

On four Manhattan rental buildings alone — the 173-unit Liberty Plaza in Lower Manhattan, the 466-unit Paramount Tower on East 39th Street, the 272-unit Brittany on the Upper East Side and the 230-unit Hampton Court in Harlem — Glenwood has saved more than $181 million in property taxes, according to the New York Daily News.

Suri Kasirer, a top real estate lobbyist who has not worked for Glenwood, said the 421a program fuels New York’s economic engine.

“Extending 421a does at least two things,” said Kasirer, a top real estate lobbyist. “It ensures continued robust development and the ability to build affordable housing to meet the needs of all of the city’s residents.”

Housing advocates dispute that, saying that the abatement is nothing but a giveaway to developers and that they would not stop constructing housing without it.

Mayor Bill de Blasio has called for overhauling the program, but aims to keep it in an altered form as part of his plans to build more affordable housing.

At the moment, Glenwood executives are focused on developing two Manhattan properties, Jacob told TRD last month: A 48-story, 257-unit rental building at 175 West 60th Street and a 19-story, 15-unit condo building at 60 East 86th Street are under construction.

The latter building is being designed by architect Thomas Juul-Hansen and is not an official Glenwood project, Jacob said. He, Litwin and Howard Swarzman, one of Litwin’s grandsons, are partnering to construct condos there — a departure from Glenwood’s rental-heavy portfolio. Although Litwin is an investor, he is not actively involved in the development of the condos.

“The site was too small for a normal rental project, and too good to pass up,” Jacob said.

The firm is steadily taking on new projects without Litwin at the helm, including Hawthorn Park, a 54-story, 338-unit rental tower at 160 West 62nd Street, which opened last year.

Big spenders

In last year’s New York gubernatorial election, LLCs tied to Glenwood outspent all other donors, according to data from the good government nonprofit New York Public Interest Research Group. In 2013, Glenwood and its affiliates were the second-biggest political donor to state-level candidates, NYPIRG data showed.

In the complaint against Silver, prosecutors peg contributions from “Developer 1” to candidates for state office and state political committees at more than $10 million between 2005 and about 2014.

Meanwhile, a report from good government group Common Cause/New York found that since 2005, Glenwood and related LLCs donated a total of $12.8 million to state politicians, including $1.2 million to Cuomo.

Since June 2013, Litwin himself made contributions to the Suffolk County Democratic Committee and Manhattan borough president candidates Melinda Katz and Gale Brewer, according to the New York State Board of Elections.

In the real estate industry’s eyes, Litwin has always been an icon. In 2012, the industry’s largest trade group, the Real Estate Board of New York, named Litwin its first honorary chairman.

Bob Knakal

And those feelings don’t seem to have subsided in the midst of the scandals. Many real estate players including Levine, Newmark Grubb Knight Frank chairman Jeffrey Gural and Robert Knakal, who earlier this year sold his company to Cushman & Wakefield, said Litwin remains revered.

“Mr. Litwin is an icon in the industry and one of the preeminent developers in the world,” Knakal said.

But Blair Horner, legislative director at NYPIRG, said he wasn’t surprised that a major New York developer was entangled in the scandal.

“From a Glenwood perspective, given they’re a major player, the fact that their name came up [in two federal complaints] didn’t surprise me,” he said.

Horner, however, said that the case paints the firm in a new light. “What surprised me is that they’re allegedly deep into illegal schemes,” he said, noting the departure from Glenwood’s industry reputation.

“The state’s system of influence peddling is designed for the highest rollers,” Horner said, “and Glenwood is a high roller.”