When Gary Barnett’s Extell Development began building One57 in 2011, he secured a $700 million construction loan from a syndicate led by Bank of America.

In hindsight, the financing deal seems like the end of an era.

In the years since, there’s been a seismic shift in the financing of new residential construction in Manhattan, particularly at the very top of the market.

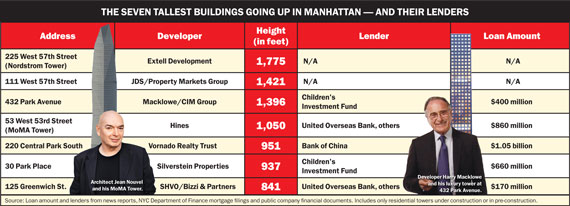

Just as wealthy foreign residential buyers are parking their cash in New York City apartments, foreign lenders are also looking to get their capital into the Manhattan market. And developers have seized on that eagerness: At least five of the seven tallest luxury condo towers under construction, or in the pre-development phase, are financed by a senior construction loan from a foreign lender, according to a review of public documents and news reports conducted by The Real Deal.

Domestic banks “have become a little more restrictive, they don’t really compete with overseas banks,” said Kevin Swill, chief operating officer of the Carlton Group, a real estate investment banking firm that has arranged financing for a number of projects. “The market is definitely very competitive, but the competition right now is coming from these overseas institutions.”

A new lending era

Traditionally, syndicates led by domestic banks such as Wells Fargo and Bank of America financed Manhattan’s major residential construction projects. In recent years, however, more unconventional lenders, many of them foreign, have stepped into the fray.

View from the $90 million penthouse at One57 (Credit: Extell Development Company)

Through an affiliate named Talos Capital Limited, the Children’s Investment Fund, a U.K.-based hedge fund that donates a large share of its profits to its eponymous charity, is financing two of Manhattan’s seven tallest residential towers. The fund ponied up $400 million for Harry Macklowe’s 432 Park Avenue and $600 million for Silverstein Properties’ Robert A.M. Stern-designed condo and hotel at 30 Park Place. (That’s in addition to a $450 million construction loan at the Zeckendorf’s 520 Park, not one of the tallest, but still a high-profile Manhattan condo tower.)

Meanwhile, the construction loans at two of the other tallest towers are coming from Singapore’s United Overseas Bank: the Jean Nouvel-designed MoMA Tower at 53 West 53rd Street, which is being developed by Hines, and 125 Greenwich Street, which is being jointly developed by Michael Shvo, Howard Lorber’s New Valley Group and Bizzi + Partners.

In addition, the Bank of China is financing Vornado Realty Trust’s under-construction 220 Central Park South, with senior and mezzanine loans totaling more than $1 billion.

Extell’s Nordstrom Tower at 225 West 57th Street and JDS Development and Property Markets Group’s 111 West 57th Street, the tallest and second-tallest planned towers in the city, don’t appear to have construction loans in place yet.

A fund with a mission

The Children’s Investment Fund is the most active — and most unconventional — backer of Manhattan’s supertall luxury towers, with $1.7 billion committed to Manhattan condo developers since 2011.

Since launching in 2004, the fund has donated more than $1.9 billion to the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, which fights childhood malnutrition and disease in developing countries and is run by fund founder Christopher Hohn’s ex-wife, Jamie Cooper-Hohn.

Initially, the fund was contractually obligated to donate a large chunk of its profits to the foundation. But the couple split in 2012, and since 2014, the fund hasn’t been required to do so. Still, Hohn remains a foundation trustee and, according to the Daily Telegraph, is expected to remain a major donor.

A rendering of 111 West 57th Street (Credit: Hayes Davidson)

The Children’s Investment Fund’s philanthropic agenda, of course, stands in sharp contrast to the swanky residential projects that it’s bankrolling in New York, which will be occupied by the über-wealthy.

Despite its exposure to the vulnerable ultra-luxury market, experts don’t expect the fund to get burned.

“The construction lending market has been extremely disciplined,” said Shawn Rosenthal, executive vice president in CBRE’s debt and finance group. “I don’t think the Children’s Fund is lending on risky projects. They have modest leverage and a fair level of interest rates.”

The Children’s Fund made its first widely publicized foray into Manhattan’s luxury condo market in 2011, when it lent Macklowe and CIM Group $250 million for their conversion of 737 Park Avenue.

Financing condo construction is undoubtedly attractive to hedge funds because of the high returns their investors expect.

The fund’s 432 Park loan to Macklowe and co-developer CIM has an interest rate of around 10 percent, according to sources. The rates on loans for 520 Park and 30 Park Place are not far behind.

Unlike most banks, hedge funds are under pressure to regularly produce double-digit returns, which limits them to riskier real estate loans. A spokesperson for the Children’s Investment Fund declined to comment. Michael Barker, an attorney at Fried Frank who has represented the fund in its Manhattan financing deals, would only cite the attractiveness of the New York market.

Getting money out

Other foreign construction lenders are satisfied with far lower returns than the Children’s Investment Fund.

For example, the Bank of China’s $600 million senior construction loan to Vornado for 220 Central Park South comes with a floating interest rate of 2.92 percent, according to Vornado’s most recent public financial statement.

The bank, which could not be reached for comment, also issued the real estate investment trust a mezzanine loan for the project with an even lower interest rate of 2.5 percent.

Vornado declined to comment, but sources said the loans are most likely cheaper because they are secured against the REIT’s sizable balance sheet.

Lenders like the Bank of China are drawn to construction financing in Manhattan not because of high returns, but because it’s perceived as safe.

“International banks look for lower yields on their loans,” said Swill, whose firm has arranged financing for 432 Park and 125 Greenwich. “They have so much capital that they need to deploy and they really want to get the money out.”

432 Park Avenue (Photo: DBOX for CIM Group/Macklowe Properties)

Sources say this influx of foreign capital has also created more competition among lenders, making construction financing cheaper for developers.

Ayush Kapahi of the real estate capital advisory firm HKS Capital Partners said the firm is “doing deals in exactly the same [interest rate] range” as the Bank of China’s loans for 220 Central Park South.

“The interest rate is a function of the magnitude of the borrower in terms of real estate holdings,” Kapahi said. “Pricing can be as cheap as what Vornado is borrowing and sometimes even cheaper. You can’t imagine.”

High risk, high return

So are foreign financiers inflating the next lending bubble?

Most experts don’t think so.

In 2008, many lenders got burned because their loans sometimes covered as much as 80 percent of a construction project’s cost, leaving them vulnerable when property values plummeted. But in the current lending cycle, this doesn’t appear to be the case.

At 432 Park, CIM has raised 60 percent of the project’s cost in equity. Since senior lenders get paid first in the event of a default, the building’s value would have to drop dramatically for the fund to lose money.

At 220 Central Park South, the Bank of China’s loans cover a much higher share of the project’s total cost, around two-thirds. But last month, Vornado announced that it has already sold $1.1 billion worth of condos in the building, meaning the bank can consider its $1.05 billion loans repaid.

There is no doubt that condo construction lending is risky and some developers may well default. But experts say that lenders, both domestic and foreign, are becoming more cautious as the luxury market slows.

“The Children’s Fund on a new loan today would be just as conservative” as domestic lenders, CBRE’s Rosenthal said.

Developers rejoice

For developers, the influx of foreign lenders is a boon.

Not only do foreign lenders often offer lower rates, but they also tend to provide simpler loan structures. Domestic banks typically lower their risk on major construction loans by bringing on other lenders in a syndicate. Involving multiple parties, of course, can complicate things when loans need to be renegotiated.

In contrast, the Bank of China and the Children’s Investment Fund keep entire loans on their books, according to sources. This can offer developers much-needed flexibility.

Perhaps most importantly, these alternative lenders offered developers funds at a time when large domestic banks were still recovering from the financial crisis and adjusting to new regulatory requirements. That goes a long way in explaining why so many of today’s high-profile towers are bankrolled by these lenders.

Harry Macklowe is the quintessential example. The developer and CIM secured their construction loan for 432 Park in 2012, a mere four years after Macklowe’s spectacular multibillion-dollar default.

Foreign lenders see that the “residential market is booming,” said the Carlton Group’s Swill.

“It’s still the safest of all real estate markets when it comes to new development,” he said.