CBRE, the world’s largest commercial brokerage, leased up more office space, by far, than any other firm in Manhattan last year.

CBRE, the world’s largest commercial brokerage, leased up more office space, by far, than any other firm in Manhattan last year.

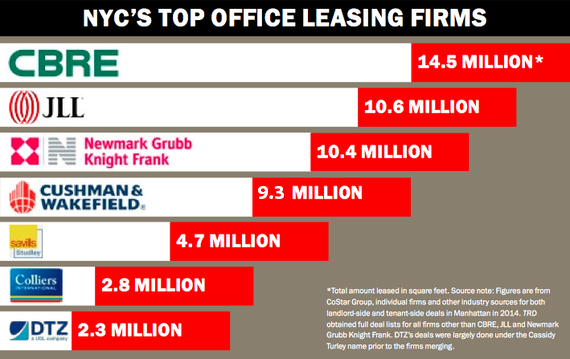

The firm unloaded about 14.5 million square feet for both landlords and tenants — or roughly a third of the 42 million square feet of new and renewal deals inked in Manhattan last year, according to a ranking by The Real Deal.

Chicago-based JLL, which notched about 10.6 million feet, ranked second, followed by Midtown-based Newmark Grubb Knight Frank, a division of the publicly traded BGC Partners, which racked up 10.4 million square feet.

The global brokerage Cushman & Wakefield took the No. 4 spot with 9.3 million feet, according to the ranking, which was compiled using industry databases, including the CoStar Group, and information from some of the firms, as well as other industry sources.

Savills Studley, which knocked out 4.7 million square feet, rounded out TRD’s top five.

Despite the fact that the Manhattan office leasing market has grown over the last year, with about 5 percent more space leased in 2014 than in 2013, most of the top leasing firms kept about the same basic market share as they had two years ago, the last time TRD ranked firms on the office-leasing front.

Still, two firms — CBRE and JLL — gained ground. JLL jumped two places in the ranking, increasing its leasing business by about 3.6 million square feet. CBRE, meanwhile, upped its total by about 1.3 million square feet. (While TRD was able to obtain the deals that made up all of the other firms tallies, it was not able to do so for JLL and CBRE.)

On the flip side, Colliers International, No. 6 on the ranking, and DTZ, No. 7, both saw their square footage drop — Colliers by nearly 300,000 square feet and DTZ by more than 100,000.

No deal is too small

To get to the top of the leasing food chain, there appears to be one cardinal rule: Don’t reject any business, no matter how small the deal.

At least that was the motto that most firms, including CBRE and Cushman, took to the bank. Indeed, TRD’s analysis found that about 70 percent of Cushman’s 562 leases were less than 10,000 square feet — a ratio that was on par with most of the other firms on the list.

And the companies that made TRD’s cut all handled an array of transactions, from simple lease extensions that brokers likely could have executed in their sleep, to billion-dollar deals that commanded an army of agents.

While the small deals pay a lower fee and do not come with the same kind of sex appeal, they can be relatively lucrative on a per-square-foot basis.

That system of juggling both large and small deals runs counter to how things work in the investment sales world, where the biggest firms largely go after the big business.

When it comes to office leasing, the firms that dominate in the Manhattan market south of 59th Street broker an extremely wide range of deals.

For example, CBRE’s Lewis Miller, a former investment banker, represented Credit Suisse in its massive 1.1-million-square-foot renewal at 11 Madison Avenue in the Flatiron District. The landlords, the Sapir Organization and CIM Group, have not revealed how much they shelled out in commissions, but using standard commission rates (including discounts for big deals), CBRE could have pocketed more than $30 million for Miller’s work alone. Another group from CBRE, along with a NGKF team, represented the landlords.

That giant transaction was one of a slew of large deals last year. In fact, 2014 saw 58 leases of 100,000 square feet or more, compared with only 43 in 2013.

“The number of large leases that were signed [in 2014] was dramatically larger,” said Steven Durels, director of leasing for the city’s largest office landlord, SL Green Realty, during the firm’s fourth quarter earnings call.

Yet while there were more mega deals to get done, CBRE also took on tiny deals, representing Lloyd Goldman’s 362 Fifth Avenue, for instance, where fashion designer By Chance inked a five-year, 1,141-square-foot deal. If a typical commission scale was used, CBRE’s commission on that transaction may have been as low at $5,000, according to TRD’s calculations.

Dana Moskowitz, president of EVO Real Estate Group, which did not make TRD’s ranking, said “small space goes quickly and we have multiple bids.”

“What we have seen in the brokerage business this year is a lot of competition for quality spaces, especially 5,000 square feet and under,” said Moskowitz, whose firm joined the NAI Global network in November.

Macho broker

The most obvious driver of Manhattan leasing activity in the last few years has been the growth of the so-called TAMI sector — technology, advertising, media and information — particularly in the hot Midtown South tech corridor.

Vornado Realty Trust’s CEO Steven Roth said last month that TAMI tenants made up nearly half of his firm’s leasing total, but a slightly smaller percent for Manhattan overall.

“TAMI tenants committed to more than 13.4 million square feet in 2014, close to 34 percent of total leasing activity,” Roth said on an earnings call last month, referring to overall Manhattan activity.

Still, while that sector is growing, many of the largest leases that the top brokerages handled involved more traditional tenants in the finance, insurance and legal worlds.

In addition to Credit Suisse, other traditional companies were responsible for gobbling up large chunks of Manhattan’s office space last year. For example, NGKF’s Neil Goldmacher led a group representing the hedge fund Taconic Capital Advisors, which signed a 39,850-square-foot deal at 280 Park Avenue.

Durels recently told company investors that the building, which is owned jointly by SL Green and Vornado, has seen significant activity from financial services.

In addition, while landlord-rep brokers (those who work for the property owners) are often more visible, tenant-rep brokers have the upper hand in the macho world of office leasing. And the tenants’ brokers are compensated accordingly, with much larger fees.

While brokers differed on exactly why tenant reps are paid more, most said that it’s simply harder to deal with the tenant. Unlike landlords, which understand all of the ins-and-outs of office leasing and have exclusive agreements with brokers, working for a tenant is a different beast. Not only do tenants often require hand-holding, they can easily switch brokers and change the scope of their requirements whenever they want.

“Tenant reps spend countless hours working on potential leads, at times without an exclusive relationship. They bring the tenants to fill space and therefore should be paid appropriately for their efforts and services,” said Robert Kaplan, managing director of leasing at Hidrock Realty, a property owner.

And different firms obviously bring different specialties to the table. A close-up on two of the firms, Cushman and Savills Studley, drives that point home.

Savills Studley — which was formed last year when the London-based Savills, a public company, purchased long-established New York firm Studley — handled media, apparel and legal clients in its 10 biggest deals. The firm, which specializes in tenant-side deals, tapped top brass Mitchell Steir and Michael Colacino to represent the media powerhouse Time Inc. in a 669,142-square-foot deal at 225 Liberty Street in Lower Manhattan and to represent Time Warner in a short-term, 943,438-square-foot renewal at 60 Columbus Circle, so that the company could stay there before decamping to its new headquarters at the under-construction Hudson Yards site. Savills Studley also handled the roughly 97,000-square-foot renewal deal that Warner Brothers inked at 1325 Sixth Avenue, and a roughly 70,000-square-foot-deal talent firm William Morris Agency signed at 11 Madison Avenue.

In contrast, the bulk of Cushman’s top deals were in finance, with companies including Mitsubishi MUFG Union Bank, Carlyle Investment Management, Jane Street Capital and the Paris-based bank BNP Paribas.

But Cushman is in flux. Late last year, the company dropped $100 million on the purchase of the investment sales brokerage Massey Knakal Realty Services, which dominates small building sales in the outer boroughs. And last month, officials announced that Cushman itself is on the block and could fetch $2 billion.

Colliers International, which ranked No. 6 on TRD’s list with 2.8 million square feet, is also in the midst of a structural revamp. Its parent firm, the Canadian FirstService, is splitting Colliers off into a new public commercial brokerage, to be named Colliers International Group.

Further evidence of change in the industry, the global DTZ, which ranked No. 7 on the list with 2.3 million square feet, and Cassidy Turley merged late last year and are now owned by a joint venture headed by private equity firm TPG Capital.

As TRD has reported, the wave of commercial brokerage mergers has led to a slew of agent reshuffling in the industry.

And insiders expect to see more of that in 2015.

“There are now a bunch of companies newly formed or newly capitalized, and everyone is making the same bold statement: We are a global brand,” Michael T. Cohen, president of Colliers tri-state region, said.

“But,” Cohen added, “everyone is going after the same limited number of slots to be a top five global firm.”

Correction: The original version of this story did not include a large deal Cushman & Wakefield brokered last year. That deal has been added to the firm’s total, which has been revised to 9.3 million square feet.