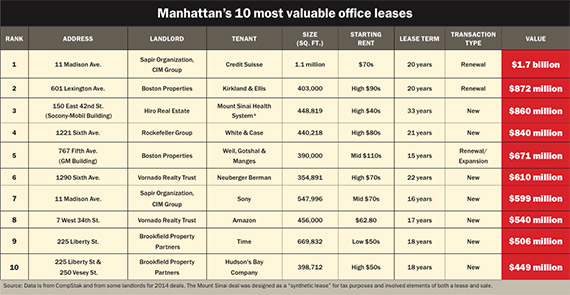

The most valuable office lease inked in Manhattan last year will bring nearly $1.7 billion in cash to the owners of 11 Madison Avenue over 20 years.

The eye-popping 1.1 million-square-foot renewal by the global bank Credit Suisse starts at roughly $84 million a year for the building’s owners, the Sapir Organization and the CIM Group. The deal blows away all other Manhattan leases signed last year in both size and price.

This month, with help from the leasing data firm CompStak, The Real Deal looked at the most valuable Manhattan office leases signed in 2014. (CompStak determined the value by adding up all of the rent payments and then subtracting free rent and tenant improvement dollars paid by the landlord.)

The top 10 leases ranged in length from 15 to 33 years and from $449 million to $1.7 billion. They included seven new deals and three expansions or renewals. And they will rake in $7.6 billion for their building owners.

Meanwhile, four property owners — Sapir, Boston Properties, Vornado Realty Trust and Brookfield Property Partners — each laid claim to two deals.

The global law firm Kirkland & Ellis, which signed an $872 million expansion deal at Boston Properties’ 601 Lexington Avenue, had the second most valuable lease. In addition, Mount Sinai Health Systems’ 33-year “synthetic” lease at the Socony-Mobil Building at 150 East 42nd Street, clocked in at No. 3. The Mount Sinai deal — a complicated rearrangement in which Mt. Sinai purchased the condo units for 33 years, after which they will revert back to the previous owner — was valued at $860 million.

Rounding out the top five were renewals by two prominent law firms: White & Case’s $840 million deal at Rockefeller Group’s 1221 Sixth Avenue and Weil, Gotshal & Manges’ $671 million deal at Boston Properties’ famed General Motors Building.

Despite Weil, Gotshal’s pricey starting rent of about $110 per square foot, the white-shoe firm chose to stay put, a fact insiders attributed to the disruptive (and expensive) nature of moving.

All of these mega deals took place against the backdrop of a strong office leasing market that has gained serious steam in the last year. Overall Manhattan leasing activity jumped to 36.7 million square feet in 2014, from 33.9 million square feet the year before, while average office asking rents jumped to about $66.50 per foot, from about $60.50, data from the commercial firm Colliers International showed.

Brokers expect another strong year for property owners.

“I think 2015 will be a good year for landlords and a tough year for tenants in Manhattan,” said Michael Cohen, president of the tri-state region of Colliers.

But beyond 2015, he predicted some market changes when it comes to chasing down value in the leasing market.

“The seeds of the next cycle are being sown as we see these migrations out of Midtown to the newly anointed more desirable areas — the West Side, Hudson Yards, [Brookfield’s] Manhattan West. The Midtown core will be the value play.”

A rendering of Manhattan West

In addition to generating big money for the building owners, these mega leases also mean multi-million-dollar commissions for the brokers and their firms.

Although big leases often come with sharply discounted cuts for brokers, all of these deals likely came with minimum commissions of $5 million for the tenant-rep firms and $2.5 million minimums for the landlord’s broker. And many of the deals likely had commissions way more than that.

CBRE took the lion’s share of the business, representing tenants on four deals and landlords on another four. Cushman & Wakefield, which had four deals in total, was right behind that. Both firms declined to comment.

While the city’s biggest offices leases have more upside than downside, they do have some baked-in risk — for both landlords and tenants. That’s because they lock both sides into a rent rate for years.

Dennis Sughrue, a real estate attorney and partner at the law firm Pryor Cashman, said a lease with a credit-worthy tenant makes the building more valuable “because you have the rental stream.” That income, of course, can also be leveraged to borrow cash, or simply help to sell the building.

But as in any bet, each side can take a hit if the market swings in an unpredicted direction.

“Who knows what the market is going to be in 15 years? [Landlords] run the risk of carrying a lease at below-market rents during the latter period of the term,” Sughrue said.

Of course, the fate of a building and lease can depend on the location.

“Nobody anticipated the steep run up in values in Midtown South,” Cohen said.

A rendering of Brookfield Place

Financial firms diluted

The 10 most valuable deals illustrate a broader market trend: Some key Manhattan office buildings that were once dominated by financial tenants have been diversifying. Indeed, only two of the top 10 deals involved financial firms.

“We have grown accustomed to seeing the tech sector absorb space that the financial sector once did,” said Cohen.

Brookfield Place is the prime Downtown example. Until recently, the office building complex was known as the World Financial Center. But it rebranded as finance companies moved out and it looked to attract non-Wall Street tenants. Both Hudson’s Bay, the parent company of Saks’ department store, and the publishing giant Time Inc. signed off on big deals there last year.

In Midtown South, 11 Madison has seen its own transformation from a one-time financial hub to a new type of powerhouse with a broader mix of tech, media and finance tenants.

While Credit Suisse, a financial firm, had the biggest lease, the company actually shrank its footprint there. That scaling back paved the way for other types of companies, like Sony and the website Yelp, to sign on.

Credit Suisse’s starting rent is in the $70-per-square-foot range — far more then the $28 per square foot it had been paying in a lease inked in the mid-1990s. In fact, when Credit Suisse first came to the building in 1995, its initial lease was for 1.1 million square feet and was pegged at “only” $500 million by the New York Times. (The lease was inked by an affiliate of the bank and the firm later expanded in the building.)

7 West 34th Street

The income factor

There’s no doubt that giant office leases impact the entire value of a building.

For example, in 2000, Vornado purchased the 480,000-square-foot 7 West 34th Street for $128 million. Today, the building is likely worth three times that.

Much of the increase in value is, of course, due to the building’s stronger revenue stream.

In 2002, Vornado raked in about $12 million per year there, according to filings from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Today that total has tripled to nearly $35 million, with about $28 million of that coming from the 456,000-square-foot office lease signed by the online retail giant Amazon late last year. The Amazon lease ranked No. 8 on TRD’s list.

Big deals also drive leasing in surrounding buildings, because smaller firms want to be near their clients, said James Caseley, executive managing director of ABS Partners Real Estate.

“They will tend to cluster around a mothership,” Caseley said.