In the 1970s, union members had a monopoly on New York City’s skyline. At the time, card-carrying union workers made up a stunning 90 percent of the city’s construction workforce. Not surprisingly, that number is down significantly today. The latest stats peg the non-union market share at 40 percent — and some say it may be as high as 50 percent.

Union contractors’ hold on the industry has been slipping for several years, but their role in NYC development has never been in as much jeopardy as is it now.

This is, indeed, a crucial time for the city’s construction industry: Costs are on the rise, skilled workers are in short supply and one of developers’ most beloved tax benefits, the 421a program, is dead — at least temporarily. And the fight over 421a is a key indication of how developers are digging their heels in on what they’re willing to pay for labor.

In blunt terms, it’s seemingly a perfect storm for a non-union takeover.

As the city continues to see a building boom, sources say non-union contractors have gained an important stronghold, especially in 20-to-25-story residential projects. A majority of residential construction in NYC is open shop — meaning it’s not exclusively union — and experts say the trend won’t stop there if union outfits can’t keep up with the financial perks offered to developers by their non-union rivals.

A big source of the non-union edge is, of course, cost: Non-union construction is 20 to 25 percent cheaper than union labor, said Louis Coletti, CEO of the Building Trades Employers’ Association, which represents union contractors citywide.

“Our ability to get the business model of building with 100 percent building trade members has been shattered, and it isn’t going to go back,” Coletti said. “Unless the business model can affect those cost reductions across the board to get that differential to 10 to 12 percent, then I think the open-shop model is here to stay.”

Over the last few years as construction costs have shot up, some high-profile developers have turned to non-union labor for the first time.

Jordan Barowitz, vice president of communications for the Durst Organization, said his firm only uses open-shop workers for its rental housing projects.

Though even that is a big shift. The company has traditionally used union outfits for major projects. That changed with Hallets Point, which broke ground this year. The project is slated to have seven residential buildings along Astoria’s waterfront, but because of the expiration of 421a, the developer is just constructing one of the buildings — for now.

Rendering of Hallets Point in Astoria (credit: Studio V Architecture)

“Historically, the Durst Organization has used union labor. Unfortunately, it has become cost prohibitive for the construction of rental housing,” Barowitz said in a statement.

JDS’s Michael Stern has been something of a poster child for the shift to open shop, with his 111 West 57th Street held up as a kind of litmus test for the trend. If a 1,418-foot tower can be built with a mostly non-union workforce — an unthinkable prospect 10 years ago — what’s to stop more developers of supertalls from going open shop?

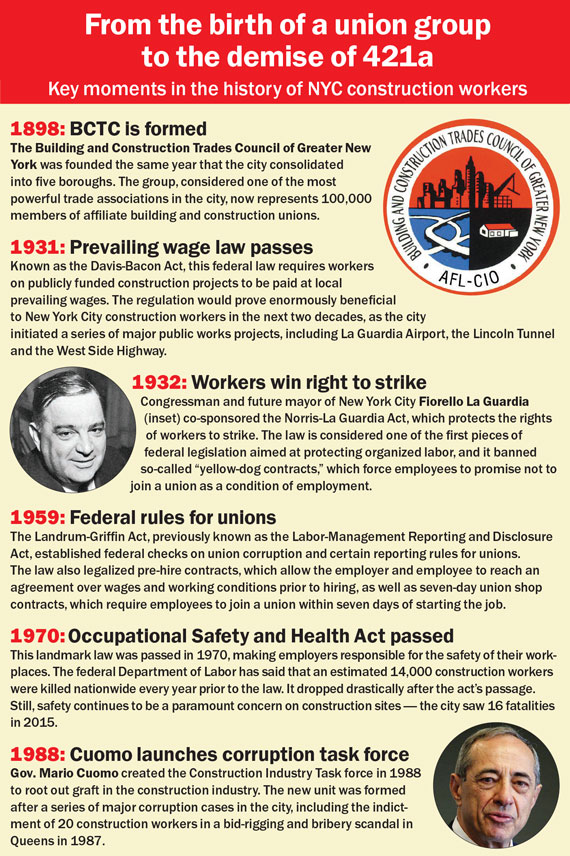

Gary LaBarbera, who represents 100,000 union workers as president of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, told TRD that while non-union labor certainly has a presence here, New York City is still a predominantly union town.

He said non-union encroachment is relegated to the city’s new residential construction. But he pointed out that 75 percent of new construction is non-residential — commercial, institutional and government-related — and completed by union contractors.

He said non-union encroachment is relegated to the city’s new residential construction. But he pointed out that 75 percent of new construction is non-residential — commercial, institutional and government-related — and completed by union contractors.

“There’s been a lot of discussion around non-union contractors, and quite candidly, there are a lot of irresponsible developers who are pushing that model,” said LaBarbera, who has taken a more combative stance than Coletti has on the issue. “The idea that the trend, overall, in the city of New York, is going non-union is factually incorrect.”

Michael Stern (Photo: Studio Scrivo)

Still, like developers, construction companies are also rejiggering their approach to bringing non-union workers into the fray.

Lance Franklin, CEO of Triton Construction, which has worked with a host of developers including HFZ Capital Group and Bluerock Real Estate, said that his company started its first open-shop project in 2005. Now, a majority of the company’s work is open shop — including SR Capital’s luxury condos at 551 West 21st and Ian Schrager’s planned hotel and condo development on Chrystie Street.

“I think the trend is not only continuing, but it’s getting stronger,” Franklin said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if in five years, the city is an open-shop city.”

Industry setbacks

During the housing crisis of 2008, projects nationwide stalled and the pipeline of new work fell to a trickle. The downturn led to some of the most experienced workers permanently dropping out of the workforce, said Manhattan-based construction attorney Barry LePatner.

With financing scarce, the developers who were actually building increasingly began turning to non-union contractors to save on costs, LePatner said. Union employees who were laid off soon began taking jobs at non-union construction companies in order to make ends meet.

A rendering of 111 West 57th Street (Credit: Hayes Davidson)

When the economy improved, these workers returned to their union jobs, but the non-union construction companies gained crucial experience that has allowed them to take on bigger projects, LePatner said.

“It’s a question of adaptation. If unions can keep their hold on larger, more complicated buildings, they are going to have one major area where they are preferred by more major developers,” he said. “There’s going to be a market force if the non-union groups get more experience to be the preferred workers for the major buildings.”

Traditionally, the appeal of union labor has boiled down to standardization: Developers believe they are signing on for efficient and quality work when they go union, arguing that organized labor brings training, experience and safety to a project. One challenge for non-union groups is that they sometimes require more supervision because training is less formal and organized, said Robert Barone, senior managing director of CBRE’s valuation and advisory services construction management group.

“In most every case, more times than not, there’s more oversight that is needed to get the quality you’re looking for,” he said. “There’s a tradeoff. When you go non-union, you’re working harder on management, harder on diligence, and you’ll probably have to fund it more fluidly to keep the project moving.”

Safety is often cited as a deterrent from opting for non-union labor, as well.

LaBarbera, for one, argues that it’s no coincidence that 15 of the 16 construction fatalities in the past year were at non-union work sites.

But safety lapses can happen anywhere, as proven by last month’s crane accident, in which a 38-year-old pedestrian was killed. The crane operator, a member of the International Union of Engineers Local 14, was following procedure and trying to secure a mobile crane due to high winds when the boom came crashing down on a Tribeca street.

In December, city officials announced legislation that would require all construction work involving buildings 10 stories or taller to be completed by workers who have gone through mandatory apprenticeship programs, which are run by unions. The proposed measure was billed as a way to increase safety at work sites, but developers criticized it as a union-friendly maneuver to assure more construction projects were union-led.

Brian Sampson, president of the New York State chapter of the Associated Builders and Contractors, an open-shop advocacy group, said claims about open-shop construction being unsafe are “asinine.”

“Their objective is to vilify honest, hard-working, safe contractors and try to convince elected officials and others that we are not safe because they know that they have out-priced themselves,” said Sampson, who prefers the term “merit shop.” “They simply want to politicize safety for their own financial windfall.”

The 421a factor

The battle between union and non-union construction came to a head in January in the heated debate over the future of 421a. In fact, the dispute is largely responsible for the lapse in the program, which offers developers tax abatements in exchange for building affordable housing.

In July, officials passed state legislation that required labor leaders and developers to reach an agreement by January 2016 on the wages developers would pay construction workers on projects that benefit from the program. The tax abatement program expired when the parties failed to strike a deal.

An agreement hinged on whether 421a projects with 15 or more units should be required to pay at these higher rates. It was a crucial moment for union members to possibly regain lost market share of residential projects.

Mayor Bill de Blasio opposed the requirement, arguing that it would stymie the city’s efforts to construct 80,000 new affordable housing units over the next decade.

The New York City Independent Budget Office, a nonpartisan watchdog, released a report last month that estimated that prevailing wages would increase total construction costs by 23 percent and increase per-unit cost by $80,000. That, the report noted, means that an additional $4.2 billion in financing would be necessary to meet the mayor’s 10-year affordable housing plan. The report, however, did not take into account how features of prevailing wages, like job site rules, government monitoring and project schedules might control construction costs and offset higher wages.

Blended workforce

To cut down on costs without dipping into workers’ pockets, experts have said unions should create a “blended-rate” workforce — one that has more manpower with a lower budget. This would mean adding more union workers who are at a lower pay grade than highly skilled journeymen.

A 2011 report by the Regional Plan Association, the urban research and advocacy group, suggested that unions need to make a series of concessions in order to remain viable players in New York City.

It estimated that non-union workers make up 40 percent of the construction market and suggested eliminating certain fringe benefits, featherbedding — the practice of hiring more workers than needed for a particular job —and time-consuming work rules to shift the scale back to union favor. When asked by TRD, representatives for the association last month declined to comment on the report, saying an updated version will be released sometime next year.

Jay Badame, president and chief operating officer of Tishman Construction Corporation, an exclusively union company that served as construction manager at One World Trade Center, said that on a “good day,” the price difference between using non-union labor and union is 10 to 15 percent — in favor of non-union — and on a “bad day,” that gap jumps to 20 to 30 percent.

Tishman has the benefit of being a well-established company with deep pockets and attractive insurance rates — qualities it hopes will hold up against their cheaper non-union counterparts.

“We will never be in a position where, on a trade-by-trade basis, we can compete with non-union companies,” Badame said at the Urban Land Institute New York’s annual Real Estate Outlook event in January. “So, I have to do some things below the line to make it more attractive for that developer to say, ‘I’m going to go with Tishman, I understand that they are going to be here for the next 50 years as opposed to the next five.’”

Jeffrey Dvorett, executive vice president and head of development at Kuafu Properties, said during the same event that safety and availability are a big consideration as his company deliberates whether to employ union or non-union labor. He said it’s still an active discussion.

“We look at it and we say, ‘Yes, there’s the price of what it looks like on paper to save the money, but at the same time, we’re a sophisticated development company,’” he said. “We care a lot about our reputation. We care about the quality of what we produce. We care about safety a lot. We also care about the schedule, so these are things that we have to weigh carefully to make decisions.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the status of legislation pertaining to mandatory apprenticeship programs. The legislation was announced and has not been formally introduced in the city.