Last year, residents began moving into TF Cornerstone’s massive new rental tower at 606 West 57th Street in Hell’s Kitchen, where some units were asking as much as $8,000 a month.

For SLCE Architects, the project with more than 1,000 apartments underscored one of the 150-person firm’s specialties: serving as executive architect alongside a big-name designer — in this case, Miami-based Arquitectonica. The 42-story development, branded the Max, was also part of the thinning wave of new, large-scale residential buildings in Manhattan.

Like 606 West 57th, most of SLCE’s projects that opened in 2018 were in the city’s most densely populated borough. But James Davidson, a partner at SLCE and head of its design department, said that’s likely to change going forward.

With project costs through the roof and a lack of buildable sites in Manhattan, New York’s top architects are adapting to new areas and diversifying the kinds of assignments they take on.

SLCE’s clients, including many of the city’s biggest developers, are increasingly looking to the outer boroughs and other markets outside of the city, Davidson noted. Manhattan sites “are difficult to acquire and augment enough to make for a viable development,” he said. “We’re noticing [that] in our conversations with developers.”

Others in the city’s real estate business have echoed that sentiment. “I can’t do anything in this town today,” developer Steve Witkoff said last month at an industry forum in Lower Manhattan. “The land is too expensive.”

Architects and developers were issued nearly 166,000 construction permits in 2018 — a slight decline from 2017 but the first drop seen since 2009 — according to the city’s Department of Buildings. Although construction volume in the city remains relatively high, architects say the slowdown in the luxury condo market means they are looking to other project types, including mixed-income housing and infrastructure. They’re also increasingly relying on renovations and conversions of existing buildings rather than ground-up projects.

And as construction becomes increasingly complex in the city — from zoning laws to building codes — many architects are becoming increasingly involved in the later stages of projects.

“It’s the architect as quarterback,” said Ariel Aufgang, founder and head of Aufgang Architects, a 44-person design firm based in Suffern, New York, which worked on Joy Construction and Maddd Equities’ mixed-use development at 411 West 35th Street. “We’re much more involved in every stage now.”

Rising by design

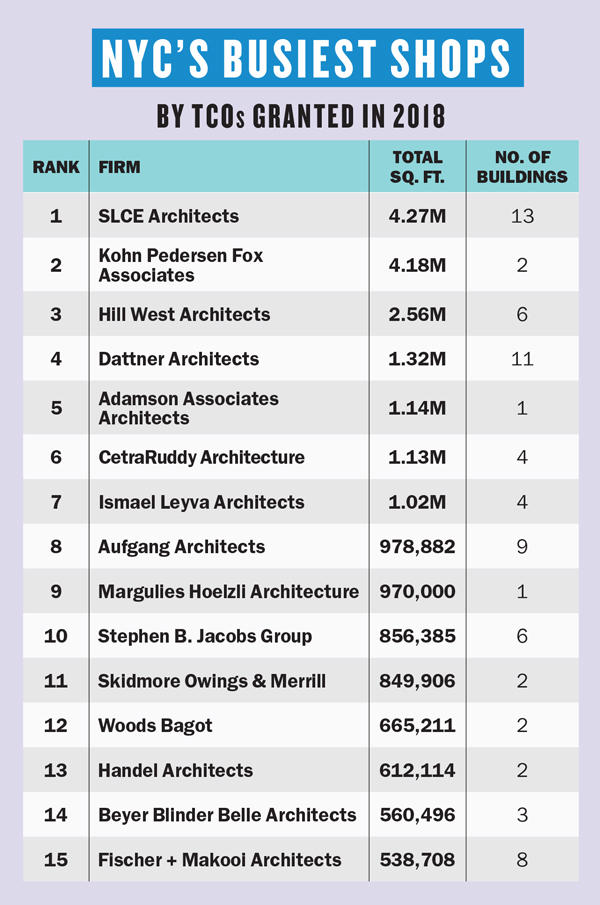

For this year’s ranking of the top architecture shops citywide, The Real Deal tallied companies based on the total square footage of their buildings that received temporary certificates of occupancy in 2018, allowing them to cross the finish line. The top 15 firms completed 21.6 million square feet worth of projects that were granted TCOs last year, which means the city deemed them safe to inhabit.

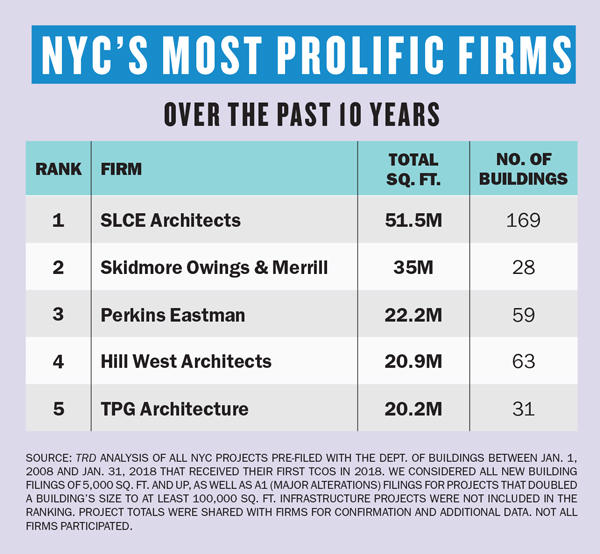

Our most recent analysis gives a snapshot of the kinds of projects that kept some of New York’s leading architecture firms busy in the past decade. During the lead-up to a project receiving safety approval, architects see their designs become reality — in some cases after more than 10 years.

SLCE once again topped TRD’s ranking. The Midtown-based firm worked on 4.3 million square feet across 13 projects that were granted TCOs for the first time in 2018. SLCE was also the most prolific architecture shop in the city over the past decade.

Kohn Pedersen Fox (KPF), an international firm also based in Midtown, followed closely with 4.2 million square feet between two buildings: Related Companies’ office towers at 30 and 55 Hudson Yards. Both are slated to open on March 15 as part of a grand-opening ceremony planned for Related’s $25 billion megaproject.

Hill West Architects, headquartered in the Financial District, ranked third with 2.6 million square feet across six projects, and Midtown-based Dattner Architects came in fourth with 1.3 million square feet across 11 projects. Rounding out the top five was Toronto-based Adamson Associates Architects, known as AAI Architects in New York, with just one building that spanned more than 1.1 million square feet.

Because this year’s ranking is based on DOB filings, it zeros in on executive architects and doesn’t count developments that don’t need to be recorded with the agency, such as projects owned by the Port Authority. As a result, 3 World Trade Center, which was designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners and opened in 2018, is not included.

T.J. Gottesdiener, a managing partner at Skidmore Owings & Merrill, which took the No. 11 spot this year, said his firm often serves as both architect of record and designer on its projects and shies away from serving as just the former.

“We want to implement what we conceive,” he said. “And we turn down many opportunities to be the architect of record for someone else.”

Movin’ out

SLCE’s Davidson said that about two-thirds of his firm’s work is full commission — including design — and the remainder is shepherding projects through the grueling planning and regulatory process as the architect of record. The latter assignments have included projects designed by starchitects Bjarke Ingels, Norman Foster and Robert A.M. Stern.

The bulk of SLCE’s projects to receive TCOs last year were in Manhattan, but Davidson said he sees the firm shifting to Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx in the next few years. He said that some of his firm’s clients have started looking at Opportunity Zones — which give developers and investors tax breaks for investing in historically distressed areas. Working on such projects could lead to even more large-scale design work outside of Manhattan, he noted.

Following TF Cornerstone’s Hell’s Kitchen rental project, spanning just under 1 million square feet, SLCE’s second-largest project was Rockrose Development’s 55-story rental building at 43-22 Queens Street in Long Island City, which the architecture firm designed in-house. (TF Cornerstone and Rockrose are both run by members of the Elghanayan family.)

Following TF Cornerstone’s Hell’s Kitchen rental project, spanning just under 1 million square feet, SLCE’s second-largest project was Rockrose Development’s 55-story rental building at 43-22 Queens Street in Long Island City, which the architecture firm designed in-house. (TF Cornerstone and Rockrose are both run by members of the Elghanayan family.)

Davidson said he had expected far more work in Long Island City to pour in after Amazon announced its plans to move to the Queens neighborhood, but the e-commerce giant’s subsequent decision to pull out could impact his clients’ next moves.

“I would’ve thought that the revitalization of a commercial element would’ve created a viable 24/7 neighborhood,” he said, noting that the area is largely overrun by large-scale residential projects. “This latest news will likely cause our developers to recalibrate their business plans.”

While half of Hill West’s assignments that were issued TCOs last year were located in Manhattan, the firm’s largest project was Tishman Speyer’s rental tower at 28-02 Jackson Avenue in LIC. David West, a founding partner of the 120-person firm, said that with the sluggish luxury condo market, Hill West is now working on more rental projects in the outer boroughs.

“We have a lot of buildings now in places where there hasn’t been much development for some time,” he noted.

Those neighborhoods include Jamaica, East New York, Coney Island and the South Bronx. West said one major difference between projects in these locales and those in Manhattan is the expectation to have a built-in parking garage.

“The buildings in these areas include substantial amenities that allow [them] to be self-contained,” while the apartments tend to be “smaller yet space efficient,” allowing for more units per building, he added.

In addition to heading outside of Manhattan for ground-up projects, more clients are opting to reposition existing buildings, said KPF’s president and design principal, James von Klemperer.

Along with 30 and 55 Hudson Yards, KPF worked on designs for SL Green and Hines’ One Vanderbilt office tower in Midtown — which is expected to be completed in 2024. But the firm is also working on the modernization of SL Green’s One Madison, which will include adding 18 column-free floors to the 13-story office tower.

“We’re a firm that has largely thrived at designing some very large ground-up buildings,” von Klemperer said, noting that it’s a sign of a city’s maturity and the industry’s responsibility “to make the best of its older buildings.”

Construction monitors

Before construction on a project begins, the bulk of an architect’s job is done. But a firm’s involvement in day-to-day site operations on the way to a TCO can vary.

“Most developers have their own methodology,” said Hill West’s other co-founding partner, Stephen Hill. “Some developers don’t need the ‘boots on the ground.’”

Gene Kaufman, head of his eponymous firm, which didn’t make this year’s top 15, said the years-long construction process can be a source of friction between architects and contractors.

Gene Kaufman, head of his eponymous firm, which didn’t make this year’s top 15, said the years-long construction process can be a source of friction between architects and contractors.

“The reality is, the contractor controls what happens. The architect is reacting and reviewing,” he said. “I think that’s something that architects have always struggled with. Contractors and architects often see things differently.”

John Woelfling, a principal at Dattner, said he and his colleagues often attend construction meetings on a weekly basis and get regular updates from construction managers on the site. Doing so helps them respond to unexpected changes, such as swapping materials to cut costs or a site condition that prevents finishes from being installed properly. Woelfling said, “a lot of discretion is left up to the individual subcontractor,” which could mean an approach to installation doesn’t jibe with what the architect envisioned.

“Construction is very complex,” Woelfling said. “No matter how good a set of drawings is, things come up … It’s the best way to get the designs we’ve documented on paper actually built.”

Aside from encountering surprises during the construction process, Woelfling said other unforeseen obstacles can halt a project. Dattner — which mostly focuses on large-scale affordable and mixed-income housing projects — had a few clients last year that temporarily stopped developments due to lack of available financing.

He said construction on more than 1,000 units of affordable housing didn’t start as planned in December due to the clients’ inability to secure Low-Income Housing Tax Credits from city and state agencies. The Trump administration’s changes to the federal tax law in 2017 — which reduced the corporate tax rate from 35 to 21 percent — reduced the value of these credits, since they are used to offset tax liability.

Changes in the tax code mean more than 16,000 units of affordable housing won’t be built in the U.S. each year, according to some estimates.

“New York State and New York City had to be more selective for what they were providing financing for,” Woelfling said. “It’s one of the consequences of the tax code changing.”

Another hurdle for architects on some projects is the lack of available expertise and materials.

Nancy Ruddy, co-founder of CetraRuddy, which ranked sixth this year, said the high volume of construction in the city can make it difficult to find the necessary manpower. And manufacturers often require licensed installers to handle their materials, as is the case with a large porcelain panel being used at Delshah Capital’s 22 Chapel Street rental tower in Downtown Brooklyn.

“It’s always better to have someone who understands the material and the system and has worked with it before,” Ruddy said.

Kaufman noted that the TCO for Sam Chang and Marriott’s dual-branded hotel on West 36th Street was held up last year because it wasn’t possible to find one company that could single-handedly manufacture the stone-framed windows.

“It never would’ve occurred to us that we’d need two guys to create two windows,” he said.