More than a decade after it was first proposed, Columbia University’s massive Manhattanville campus has started to take shape in earnest, with two of the biggest buildings now open: the 450,000-square-foot Jerome L. Greene Science Center at 3227 Broadway and the 60,000-square-foot Lenfest Center for the Arts at 615 West 129th Street.

Columbia President Lee Bollinger touted the local benefits of the expansion, which will include about 15 new buildings and an acre of public green space, last summer. He said the new campus would employ about 2,500 people over the next decade and that the school would commit $150 million in benefits to the West Harlem neighborhood, including $20 million for an affordable housing fund.

Despite those windfalls, the campus has faced ongoing community protests and a series of legal battles over the use of eminent domain. But the courts eventually ruled in Columbia’s favor, and the biggest hurdles for the Ivy League school now appear to be in the rearview.

David Carlos, a senior managing director at Savills Studley who specializes in working with nonprofits, described the new campus as a game changer for universities in New York City. “It was very complicated and a bit controversial, but given who they are, they were able to get it done,” he said, adding that Columbia’s new campus has redefined West Harlem and “will allow the university to grow and expand for the next 50 years.”

And that’s one of dozens of higher educational institutions in the city.

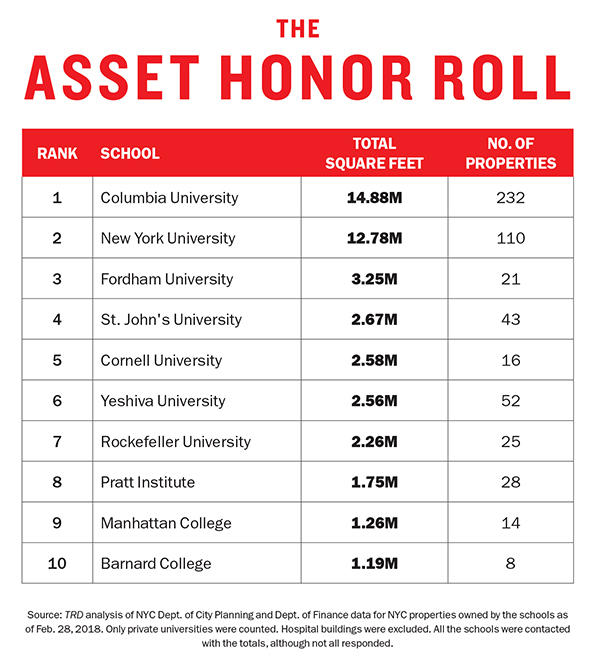

To find out just how much property New York’s biggest schools control in the five boroughs, The Real Deal ranked the leading private colleges and universities by the total volume of their real estate holdings. The top 10 schools combined owned more than 45 million square feet across 549 buildings and lots as of Feb. 28, our analysis of data from the Department of City Planning and the city’s tax assessment roll shows.

Properties held by CUNY and SUNY were not counted since both are public institutions and occupy city- and state-owned properties — making the concept of ownership less meaningful. University-owned hospitals were also excluded since they operate as separate businesses from the schools.

Educational giants

When Seth Pinsky spent his first year at Columbia University in 1989, the school had to work a lot harder to persuade students that its Upper Manhattan location was a safe place.

“Their whole pitch was: We have a real campus, unlike other schools in New York. You can be safe here. We have control of our immediate neighborhood, so we make sure that nothing too scary happens in Morningside Heights,” the RXR Realty executive and adjunct senior research scholar at Columbia recalled.

Fast-forward nearly three decades, and the city is seeing plummeting crime rates and skyrocketing property values. And Columbia — now about halfway through its expansion plan spanning roughly 17 acres — is causing more concerns about gentrification than safety.

NYU is upping its real estate book as well, most notably with plans for a 735,000-square-foot building at 181 Mercer Street in Greenwich Village.

The higher-education giants took the top two spots in TRD’s analysis by notably wide margins. Columbia came in first with roughly 14.9 million square feet across 232 properties, and NYU followed with about 12.8 million square feet across 110 properties. (By comparison, the city’s largest commercial landlords, SL Green Realty and Vornado Realty Trust, reported at the end of last year that they had stakes in Manhattan buildings totaling 29.5 million and 23 million square feet, respectively.)

The two universities essentially bookend Manhattan, with Columbia’s stronghold Uptown in Morningside Heights, and now Harlem, and NYU’s Downtown in and around Greenwich Village. NYU also owns the Tandon School of Engineering in Brooklyn’s MetroTech Center, among other real estate holdings in Brooklyn and the Bronx.

The numbers drop significantly after that.

Fordham University in the Bronx came in third with about 3.3 million square feet across 21 properties, followed by St. John’s University in Queens with roughly 2.7 million square feet across 43 properties. Cornell University, based in Ithaca, New York, rounded out the top five with roughly 2.6 million square feet across 16 properties in the city.

Fordham owns the largest single New York City real estate asset among all the private universities — an academic building at 441 East Fordham Road that spans about 1.7 million square feet. Columbia and NYU’s biggest properties are both 1.5 million square feet each.

Spokespeople for Columbia and NYU provided information for this story. Representatives for Fordham and Cornell declined to comment, while a representative for St. John’s did not respond to multiple requests.

On average, the city’s biggest universities have seen their property holdings grow by more than 150 percent over the past 15 years, according to TRD’s analysis of city records. That’s a notable increase for any industry outside of the core real estate business.

“The schools are going to fluctuate with population trends, and population trends in the city are very, very positive,” said Bob Knakal, who chairs Cushman & Wakefield’s New York investment sales division.

Building for prestige

Even as U.S. student debt reportedly swells to an estimated $1.4 trillion and the college experience continues to migrate online, having a large physical footprint — from academic and office space to rental housing and even condominiums — remains a huge incentive for private universities in New York.

In addition to giving faculty and students more space to work, study and live in, expanding a campus (and acquiring properties outside of it) has become one of the clearest ways to demonstrate that a school is doing well.

And while brokers and developers say direct competition between schools and real estate firms is rare, the ongoing expansion of educational institutions increases the chances of rivalries over buildings and development sites going forward. The shrinking supply of buildable land in and around Manhattan doesn’t help.

“The more schools expand away from their campuses, the more they’re competing with developers who are looking to do residential projects,” said David Falk, president of the New York tri-state region at Newmark Knight Frank and a frequent broker for Pace University.

What a developer sees as the best use of land, in many cases, “may not match with what the university is looking to do,” he added.

The main advantage that developers have over schools when looking for a new site is the ability to act fast, while the main advantage that schools have over developers is the ability to pay top dollar, according to industry sources.

Carlos noted that universities also generally have more options for financing projects than developers, since their nonprofit status enables them to use tax-exempt bonds and they are far more likely to receive private donations.

“Unfortunately for developers, nobody is writing them a check and donating to their cause,” the Savills Studley broker said.

He contrasted that with sites owned by Columbia and NYU, where “many buildings go up with naming rights that trade for tens of millions if not hundreds of millions of dollars.”

A contentious expansion

Columbia unveiled its Manhattanville project — which will run for the most part between West 125th and West 134th Streets and from Broadway to 12th Avenue — back in 2003. The university received approval from the city to rezone the area for academic mixed-use development in 2007 and began pre-construction work in 2008.

The massive project also involved a roughly two-year battle over eminent domain, which the Empire State Development Corporation used to seize buildings and allow the entire campus to run uninterrupted.

The massive project also involved a roughly two-year battle over eminent domain, which the Empire State Development Corporation used to seize buildings and allow the entire campus to run uninterrupted.

The Singh and Sprayregen families, who owned storage warehouses and gas stations in West Harlem (totaling about 9 percent of the 17 acres) sued the state in 2009, claiming the use of eminent domain was not relevant because Columbia is a private institution. A state appellate court sided with the families, but the New York Court of Appeals reversed its decision the following year, allowing the expansion plan to move forward.

The Jerome L. Greene Science Center and Lenfest Center for the Arts were completed in October 2016 and April 2017, respectively. Other buildings on their way include the University Forum and Academic Conference Center on the busy corner of 125th and Broadway and a new home for Columbia Business School on Broadway between 130th and 131st streets.

The total cost of the Manhattanville campus, which is expected to be completed by 2030, is pegged at about $7 billion, and Columbia is financing it through a combination of donations and university funds. The school’s endowment is currently valued at just under $10 billion.

Columbia faced virtually no competition from developers as it purchased the land for the expansion, according to sources. But the school began to face competition from smaller buyers once property owners in the neighborhood realized it was putting an assemblage together and put their land on the open market in hopes of increasing the price, said Shimon Shkury, president of Ariel Property Advisors.

“Let’s say you have a parcel that’s 100 by 100 [feet],” he said. “You’d put it on the market because other people outside of that area would have an interest in the lot as a standalone, whereas Columbia had further interest because it was part of their puzzle.”

Lingering opposition to the plan these days mostly comes from small businesses and local officials.

Ana Diaz, operations manager at the auto repair company 2000 Auto Service Corporation at 2315 12th Avenue — which Columbia purchased for $8 million in 2007 — said the school’s aggressive push into the neighborhood has put a major crimp in small businesses like hers. Her shop is now on a month-to-month lease, and nobody knows how much longer it will stay there, she noted. “At any point in time, they could easily say, ‘Hey, you have 30 days to relocate,’” Diaz said.

And City Council member Mark Levine, who represents the district, said the expansion has already started to drive up rents for local residents. He predicted that would become more of a problem as the project moves closer to completion, “putting the neighborhood out of reach of low-income families and even some middle-income families as more people connected to the new campus move in.”

Columbia spokesperson Victoria Benitez, who noted that gentrification had been occurring in Harlem and throughout the city long before the school started its expansion plans, said the university has not turned a blind eye to that. “As part of our community benefits agreement, we are committed to support affordable housing and support tenants’ rights in our community,” she told TRD in an emailed statement.

A downhill battle

NYU’s Mercer Street project — which will contain about 60 classrooms, a 350-seat theater, dining space, a gym and student and faculty housing — has faced community opposition as well. The concerns range from population density to the university cutting down cherry trees to make way for construction.

The ground-up development is part of NYU’s Core Plan initiative, which launched in 2007 and allows the college to develop new facilities on a pair of “superblocks” between West Third and West Houston streets. The City Council approved the plan in the summer of 2012, and pre-construction on 181 Mercer began in February 2016. The sprawling property is due for completion in late 2021.

Like Manhattanville, NYU’s Mercer Street project has faced a court battle as well, with locals arguing that the development site was designated as parkland. In 2015, the New York State Court of Appeals ruled in NYU’s favor, and the university agreed to build one building at a time to avoid overwhelming the neighborhood.

NYU acquired the Mercer site from the state’s Dormitory Authority in 1993, property records show. The total project cost is pegged at about $1.3 billion, and NYU intends to pay for it with a $947 million loan, a $300 million fundraising campaign and $38 million from university funds, according to a 2016 presentation from the school. As of last August, NYU had an endowment of roughly $4.1 billion.

Local resident Beth von Benz has been a vocal critic of the university’s plan for years, arguing that it embodies NYU’s mentality that it essentially owns Greenwich Village. “What do they really give back to the neighborhood?” she said. “Or what are they planning other than building this monstrosity?”

But Pinsky said it’s important for institutions like NYU and Columbia to expand, given the contributions they make to the city’s economy and well-being. “We have to make sure that in taking community sentiment into account, we’re not allowing narrower interests to overwhelm the greater good,” he maintained.

An NYU spokesman said the school was committed to working with its neighbors and provides information about its construction projects online for the public to see.

Real estate’s best friend?

For the city’s real estate industry, most university expansion projects are a welcome change, since they provide more potential tenants and shoppers and almost always have a positive impact on property values. And while New York real estate can be notoriously cutthroat, multiple developers said they prefer to collaborate with schools rather than compete with them for land.

The Brodsky Organization, for instance, has a luxury rental apartment building called Enclave at the Cathedral located right by Columbia at 400 West 113th Street. Company partner Thomas Brodsky said the university’s presence was one of the main reasons the firm was interested in Morningside Heights, since it helps ensure that there will be an almost permanent demand for housing there.

“We don’t have a formalized relationship with Columbia, but I think that we advertise in the Columbia Spectator,” he said, referring to the school’s student newspaper. “About 75 percent of our market-rate [tenants] are from the Columbia community, whether it be undergrads, graduate students or professors. So we kind of offer a nonofficial off-campus housing option.”

The Durst Organization’s Jordan Barowitz noted that the universities can also serve as potential clients for developers, citing a building that his firm developed for the New School at 65 Fifth Avenue in 2014. The property contains the school’s University Center along with its dorm Kerrey Hall, which houses more than 600 students.

Barowitz said it was conceivable that Durst had competed with a private university at some point, given its long history, but he was unaware of any recent instances where the company was going after the same site as an educational institution.

“I think there’s more opportunity for collaboration than competition with schools,” he said. “Like, they oftentimes own large pieces of property that have zoning that’s unfulfilled.”

But rivalries between the two industries still occur from time to time.

Early last year, for example, the New School paid $153 million to buy a five-story office building at 34-42 West 14th Street in the heart of Greenwich Village from Samson Associates. A team from Meridian Capital Group led by Helen Hwang and Karen Wiedenmann represented Samson, and while Hwang declined to name the other parties interested in the site, she said the deal pitted the school against several investor groups and generational family owners.

The broker said her client ultimately chose the New School because of the price it was willing to pay and how quickly it was able to move on the building. That came with one additional perk.

“When you sell to a not-for-profit, there is an economic benefit to the seller, because you don’t have to pay the transfer tax,” Hwang said.

But she emphasized it’s important to remember that universities and other nonprofits are not always just thinking about finances. “You have to be really cognizant of the fact that their mission is not all economic,” she said.

Seeing the bigger picture

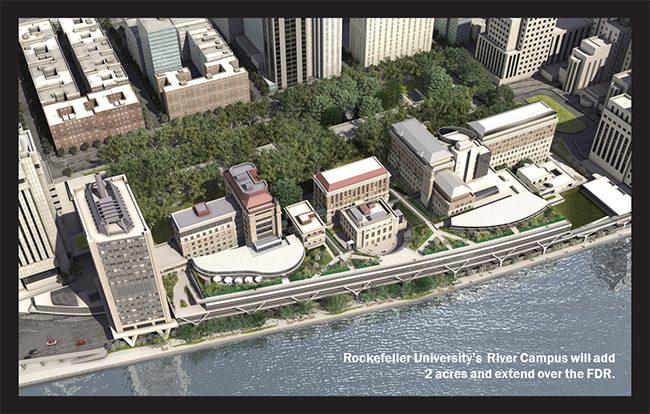

Take Rockefeller University, which focuses on research in the biological and medical sciences. The school, located on the Upper East Side, is working on its Niarchos Foundation-Rockefeller River Campus initiative, which will add 2 acres and several buildings to the school’s campus — extending it over the FDR Drive. Rockefeller took the No. 7 spot on TRD’s ranking with 2.3 million square feet across 25 buildings.

But the 117-year-old university, with an endowment of about $2 billion, has made it clear that the expansion is not a standard real estate play. Rockefeller’s associate vice president of planning and construction, George Candler, said the goal is to upgrade the school’s labs and noted that the school secured air rights for the space in the 1970s.

“To compete with other top-flight universities, you have to provide really good facilities,” he said. “And with some of these old buildings, you could throw as much money as you can think of at them, and you’d still come out with a mediocre lab just because the floor-to-floor heights are too low and the buildings are too narrow. … So it made more sense to develop a new, more adaptable, flexible building.”

Over the years, Candler said, the university has found that horizontal space is more valuable for research labs, since it works better at promoting the types of interactions between scientists that can spur discoveries. For that reason, Rockefeller — which has little interest in the high-flying real estate game — doesn’t try to make its projects as tall as possible.

“Even though most people in New York City would say maximize your land use and build high, a tall building with a small footprint is not good for research,” he said. “We’re not in the development business. We only build facilities that we need for our mission.”

The New School’s chief operating officer, Tokumbo Shobowale, echoed that sentiment when asked about the university’s real estate strategy.

“We are mainly about our academic mission,” Shobawale said. “If that mission requires that we develop something, we do that, but our goal is to educate.”

The New School, which was founded in 1919, has pursued a strategy of consolidation over the past decade. The university now owns just over 1 million square feet across 14 buildings, according to city records. That puts it below Barnard College, the No. 10 school on our ranking by square footage. The New School’s purchase of 34-42 West 14th Street was part of a plan to bring its various departments closer together and provide students with more opportunities to collaborate. Its administrators also wanted to give the university more of a campus feel.

“The world in 1970 was a different world. Things were much more Balkanized,” Shobowale said. “You could be just a fashion designer and not really relate to anything else. You could just be a political scientist. Now all these things are really coming together.”

Pinsky said the mentality of universities has changed over the years as well — with more schools thinking about the greater role they play in the city (and with some investing in real estate for profit.)

And as New York continues to attract large-scale development, educational institutions and traditional real estate firms could start to face off against one another more often, the RXR executive added. He said he hopes that leads to increased collaboration rather than increased competition.

“Traditionally, many of the schools were located in places that were less likely to see big institutional private developers investing,” Pinksy noted. “But I think as more and more of the city has become desirable, it’s likely that private developers and institutions will be running into each other more frequently.”