The first time David Kramer visited Roosevelt Island, it was to run a 5K race. The route looped around the thin, nearly two-mile-long stretch of land, which is sandwiched between Midtown Manhattan and Long Island City on the East River.

That was 1996, a year after Kramer joined Hudson Companies. In 1998, Hudson and Related Companies struck a deal with the city to build Riverwalk, a nine-building residential complex that would mark the beginning of the island’s redevelopment (two of the buildings have yet to be constructed).

“It’s been a very methodical evolution,” said Kramer, president of Hudson.

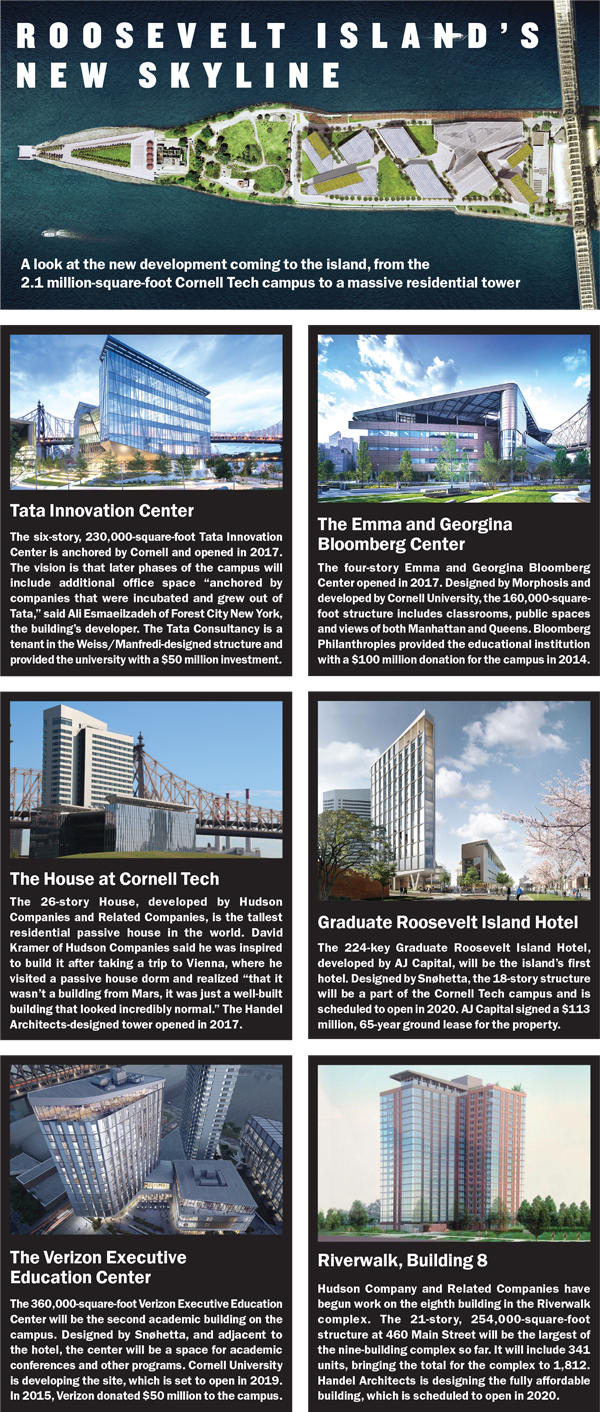

In the last few years especially, Roosevelt Island has been rapidly transforming from a suburban oasis into what some hope will be the “nucleus of all things tech.” In addition to Hudson and Related’s residential development, changes include the makeover of a retail strip on Main Street, the opening of Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park in 2012 and the introduction of ferry service to the area last summer. Most significantly, the first phase of the 2.1 million-square-foot Cornell Tech campus opened in the fall of 2017.

Real estate values have risen in kind. Last fall, a condominium at Related and Hudson’s 415 Main Street sold for $1.87 million, setting a record for the area. “The rents and condo prices that we’re getting today are well beyond our wildest expectations a couple of years ago,” Kramer said.

And between Cornell Tech and Hudson and Related’s eighth residential tower at Riverwalk, Roosevelt Island is slated to see nearly 1 million square feet of development by 2020.

“There’s been a lot of stuff brewing,” said Adelaide Polsinelli, a real estate broker with Eastern Consolidated who is marketing two commercial condo units on Roosevelt Island. “And now it’s coming to fruition.”

From sanatorium to school

In 1828, the City of New York paid $32,000 to buy what was then Blackwell’s Island, which

had been owned by the Blackwell family for several generations. There, the city operated a small pox hospital, sanatorium, prison and other facilities for nearly a century. It wasn’t until 1921 that the city began to breathe new life into the island. It was renamed Welfare Island, and new hospitals were built. The prison was eventually relocated to Rikers Island.

The real change started in 1969, when the state entered a ground lease for the sliver (today a state agency called Roosevelt Island Operating Company oversees its development). Two years later, the island was renamed again, this time for Franklin D. Roosevelt. The first residential buildings came in the 1970s and were designed as middle-income housing under the Mitchell-Lama program. The tram began connecting Roosevelt Island residents to the city in 1976. In 1989, the 22-story, 884-unit Manhattan Park apartment tower opened, as did the island’s sole subway stop.

After that, there was little development until the 2000s, when construction on Riverwalk began, and the Octagon, a former insane asylum, was converted to rentals. The island’s first four residential towers began exiting the Mitchell-Lama program after the recession, and two of them have since been privatized.

Then, in 2011, with the goal of boosting the city’s tech sector, the Bloomberg administration put out a request for proposals to develop a 12-acre swath of the island as an engineering school. Out of seven bids, the administration selected a joint venture by Cornell University and Technion-Israel Institute of Technology.

The campus, located south of the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge, already has 300 students and three buildings. Those new structures are sleek, airy and sustainable, and they stand in stark contrast to the prosaic, red-brick apartment buildings to the north of the bridge.

“The campus has generated a lot more positive energy,” said Ali Esmaeilzadeh, a senior vice president at Forest City New York, the developer of the Tata Innovation Center. He said the hope is that with time, startup tenants housed at the facility will eventually take on more space, and that Roosevelt Island will “become a nucleus of all things tech.”

A population in flux

Soon, it’ll be more than just energy that changes on the island.

Although Roosevelt Island still maintains a relatively large stock of rent-stabilized housing, both incomes and real estate values are on the rise. The median income had increased significantly since 2000, rising from $49,976 at the turn of the century to $86,483 in 2016, according to the most recent American Community Survey data. That’s compared to $55,191 across the entire city.

Meanwhile, the median home sale price crossed the $1 million threshold in 2016, according to data from real estate information provider Attom Data Solutions. And while rents citywide have fallen, the median on Roosevelt Island increased to $2,990 in 2017, up 3 percent from the previous year.

Margie Smith, a longtime resident and Community Board 8 member until April, said affordability was important to the island’s residents.

“We want development, we want green space,” she said. “And we want it to remain affordable.”

Joshua Eisenberg, an executive vice president at property management firm Urban American, which took over the residential tower Roosevelt Landing in 2014, said he expects reasonable but not excessive rent growth over time.

“The Cornell Tech campus is only half built, so you are going to see more jobs and more students,” he said, but the proximity to Manhattan and Riverwalk’s last buildings will take care of some of the absorption. “I don’t see a massive push” onto the island, he said.

With the additional housing built, RIOC estimates that the population has grown to 14,000 from 12,000 since 2010. And one apparent demographic trend is the change in the racial makeup of the neighborhood. The African-American and black population was cut by nearly a third between 2010 and 2016, dropping from 27 percent of the population to 15 percent, according to ACS data. In that same period, the Asian population more than doubled, hitting 25 percent, up from 10.

Suzanne Wolfe, a broker with the Corcoran Group who has listings at Rivercross and Riverwalk Court, said that most of her clients are Roosevelt Islanders looking to relocate nearby.

“The vast majority of buyers are young families already living on the island,” she said.

Though it’s too early to feel the effects of the campus, which is slated for completion in 2043, Polsinelli said the demographics are changing. “There’s a different kind of demographic now; younger, more mobile people,” she said. “They kind of feel like they’re in suburbia.”

Indeed, the island still feels like a bedroom community and is hardly a destination for most Manhattanites. Even with the revamped retail, it’s still a one-of-everything town: one pizza shop, one Thai restaurant, one grocery store and one public school. There are some efforts to make the island more attractive to visitors, including plans to rebrand it as an arts destination, according to Smith.

However, unlike other parts of New York, Roosevelt Island isn’t overcrowded or overdeveloped, which gives developers a certain freedom to innovate. Polsinelli is marketing two commercial spaces at Island House (which recently converted from co-ops into condos), one of which includes a pool. She said her potential clients have included an Olympic swimming team, a rehabilitative therapist and a gallery space, but she has a couple ideas herself.

“It could be a drone station, a cube, a hologram,” she said. “Something fun.”

Correction: A previous version of this article mistakenly reported that Eastern Consolidated‘s Adelaide Polsinelli is a long-time resident of Roosevelt Island. She is not.