From left to right: Kent Swig, Yair Levy, Harry Macklowe and Aby Rosen could be personally liable to lenders.

Contrary to popular belief, commercial lenders did not throw out all of their standards in the recent cycle of easy credit.

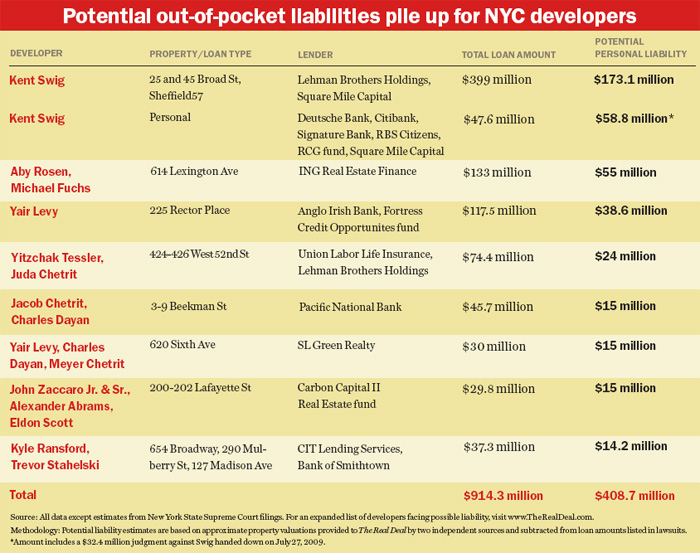

When developer Aby Rosen structured his $133 million loan for the acquisition and development of the Shangri-La hotel at 614 Lexington Avenue in April 2007, the mortgage document included a personal guaranty to cover losses in the event of a default.

Similarly, when Kent Swig negotiated $49 million in loans with Lehman Brothers Holdings to develop a hotel and condo project at 45 Broad Street in the Financial District in 2006 and 2007, the bank demanded a similar guaranty in the mortgage documents.

And other big-time borrowers such as developer Yair Levy and investor Steven Elghanayan have made the same types of commitments to convince banks to make loans on their projects.

Now, with the economy still hurting and construction stalled, lenders are looking to collect on those guarantees and are suing those borrowers to do so.

“The lenders realize they need to commence the actions because there is a risk the borrowers will go bankrupt,” said real estate attorney Terrence Oved, partner in law firm Oved & Oved. He is representing about a dozen borrowers either negotiating with or being sued by their banks.

“Lenders see everyone is underwater,” he said.

The filings are putting additional pressure on borrowers who may have to sell assets to cover their loans — or file for bankruptcy.

Personal guarantees, also known as “recourse” guarantees, are most frequently included in construction loans, but may also be part of a lease contract or a personal loan.

They are promises to pay back debt using a guarantor’s personal assets, or to pay back any shortfall should a loan be foreclosed on and the property sold.

The Real Deal reviewed nearly 30 lawsuits filed in New York State Supreme Court over the last 14 months, in which lenders from banks to private equity funds claim 30 developers are liable for a cumulative debt estimated to exceed $400 million.

The personal guarantees in question provide security to lenders at different levels. Some require the developer to pay the entire debt back, while others cover only a prescribed amount. For example, lenders claim developer Harry Macklowe is liable only for shortfalls in the predevelopment budget on the Drake Hotel site on Park Avenue — a debt they value at $849,877 — on a $482 million loan.

But most are deficit guarantees to pay the lender the difference between the loan value and the sale price after a foreclosure, which can easily climb into the millions of dollars.

At the height of the market, many borrowers were able to include provisions in their mortgage documents that limited their liability. Banks attempted to carve out protections within otherwise nonrecourse loans, but could often only win inclusion of so-called bad-boy guarantees that gave them rights only if the borrower did something wrong.

However, as borrowers took on more projects, or banks tightened lending standards, they occasionally won more lender-friendly recourse provisions.

In New York State, when a lender goes after a borrower, it must make a choice between suing to foreclose or pursuing the personal guaranty. (The two options can be pursued sequentially, but not at the same time.)

In the majority of the construction loan lawsuits analyzed by The Real Deal, the lenders sued to foreclose first, while also laying out their demands for the personal guarantees.

Lenders are claiming deficit guarantees against a pair of young developers, Kyle Ransford and Trevor Stahelski, principals at Cardinal Real Estate Investments. They are being sued in foreclosure actions totaling $37.2 million by two lenders on three Manhattan projects.

Commercial lender CIT Group is after them for a project their California-based firm developed in Soho at 290 Mulberry Street, and another in Noho at 654 Broadway, for a total of $29 million. The Bank of Smithtown, meanwhile, sued to recover $8.2 million on a construction project at 127 Madison Avenue.

In the cases against the pair, the lenders state in court filings that they want a sale of the properties, and then demand the developers make up any loss on the loan, which could climb above $14 million, as values have declined by as much as 50 percent.

Occasionally, however, rather than suing to foreclose, the lender sues for the money first.

In Long Island City, a developer borrowed $17 million from U.S. Bank to purchase a parcel for an Aloft hotel. The development stalled, and the bank sued the developer for the $17 million, but also sued four guarantors seeking an estimated $5.2 million.

The demands by lenders often come at the end of a long negotiation process that has broken down. Oved said in many cases, the suits are brought to put additional pressure on borrowers. “It is not uncommon for a lender to commence an action as a way to telegraph to the borrower” that it is serious about its claims, he said.

Most seek to resolve the situation before a judgment is awarded. “It is a death knell for a developer to have a judgment against them,” Oved noted.

Although borrowers have been known to squirrel away their assets or transfer them to family members to keep them from creditors, Oved said that once a legal action begins, a judge can bring those properties back into court.

One way out for the borrower is if the lender takes the property back at the loan’s face value at a foreclosure auction. “If the auction produces a successful bid for the full amount of the loan, the guarantor is off the hook,” said Scott Tross, a partner with law firm Herrick, Feinstein.

Many loans could be tied up in litigation for years, said David Schechtman, a senior director at Eastern Consolidated, who worked as a litigating attorney on recourse cases for six years. “More often than not, the rule of thumb is that banks will recover less on the personal guaranty than the contracts provide,” he said.

And lenders can negotiate the amount of liability. Schechtman said solvent, good-intentioned borrowers are likely to reach a resolution with the lender. Less established borrowers, he said, would “be better served cooperating at all times with their lenders.”

Swig, whose firm Swig Equities has stumbled in a number of developments, including Sheffield57, is facing the greatest number of suits. He’s battling Lehman Brothers Holdings at two buildings, and a half-dozen lenders are seeking repayment from him of $58.8 million in personal loans. He’s said he may have to file for bankruptcy, if a $32.4 million judgment is enforced on a loan tied to Sheffield57.

Judgments on personal or commercial loan guarantees are generally easy to win, but getting paid can be far more difficult, real estate attorney Luigi Rosabianca said.

“Personal guarantees are a slam dunk,” he said. “[But] you will spend far more resources post-judgment finding the assets.”