It was a Sunday evening in September 2008, and David Levinson was leaning over the balcony at a hotel in Paris. He and his wife, Simone, were on a romantic trip to the City of Lights, and Levinson had stepped out to digest some worrying news: Lehman Brothers, the financial behemoth backing two of his most important projects, might file for bankruptcy.

Surveying the lights of the French capital, Levinson took solace.

“I remember looking out at the Eiffel Tower and saying to my wife, ‘They’ll figure it out, there’s no way,’” he told The Real Deal during an interview at his 18th-floor, West 57th Street office last month. “I had a great night’s sleep thinking that. But then I woke up, and the world was different.”

The very next day, on September 15, Lehman filed for Chapter 11. The filing remains the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history. Chief among the investment bank’s $600 billion in assets were several that belonged to Levinson’s company, L&L Holding, including its most ambitious project: 425 Park Avenue.

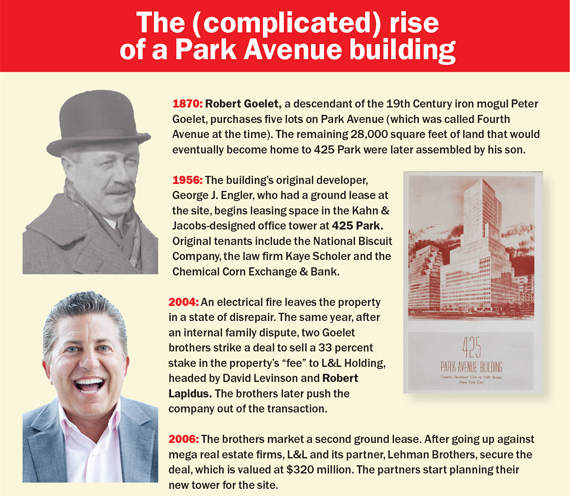

Levinson, the company’s chairman and CEO, and his partner Robert Lapidus, the firm’s president and chief investment officer, had already spent four years and millions of dollars securing the Park Avenue site, a dilapidated office building at the corner of East 56th Street. With Lehman as their majority equity partner, the duo had planned to tear it down to make way for the first new office building on Park Avenue in nearly 50 years.

It had been a messy deal even before Lehman collapsed, and Levinson wasn’t about to let it go now. “It was a near-death experience,” he said of the bankruptcy.

Fast forward to 2016, and 425 Park, which is still under construction and scheduled for completion in 2018, now holds the record for the highest price per square foot, at $300, ever paid for a Manhattan office space. The lease with asset management firm and hedge fund Citadel clocks in at more than three times what tenants are paying on average at the World Trade Center and Hudson Yards, and even exceeds prices at the notoriously pricey GM Building.

The 47-story, 670,000-square-foot building is expected to draw some of the wealthiest firms on the planet — from high-end family investment offices to private equity firms to sovereign wealth funds. Billionaire hedge fund manager Ken Griffin’s personal office will top the tower, while restaurateurs Daniel Humm and Will Guidara, of Eleven Madison Park fame, are planning an eatery on the ground floor.

Video marketing materials for the property play like scenes from modern-day “Batman” films. And Levinson called the tower a “Seagram Building for the 21st Century.”

Others seem to agree. “I’m a huge believer that there is Park Avenue and then there is everything else, but the product on Park Avenue is old,” said commercial broker Bill Montana of Savills Studley, who is not involved in the project. “You can put a lot of money into these old buildings, but they still have old bones. What L&L is doing is taking it to a whole new level. It is going to be an iconic addition to the skyline. It is going to lift up the rest of the avenue.”

But the reimagined 425 Park Avenue almost never got off (or out of) the ground.

Lehman’s demise was actually only one of a slew of major obstacles — from beating out NYC mega developers to securing the ground lease to navigating bizarre zoning restrictions to dealing with a partner’s family drama. And the building has proved to be one of the city’s most complicated construction jobs.

Levinson, meanwhile, has documented the roller coaster ride in a diary complete with sketches of the building and notes on the deal.

“I knew that we should record this,” Levinson said. “It will be a good read for my children and for Robert’s.”

Getting to know the Goelets

Before there was Levinson and Lapidus, there were the Goelets.

The family that owned the land beneath 425 Park included three brothers descended from Peter Goelet, an ultra-wealthy 19th Century ironmonger and merchant who used profits from the Revolutionary War to buy up Manhattan real estate. According to historical news reports, the family fortune was valued in excess of $60 million as early as 1902. That’s roughly $1.5 billion in today’s dollars.

But behind closed doors, there was drama unfolding in the Goelet clan. In 2004, a family dispute forced out one of the three brothers and put the land beneath the building (or the “fee”) in play.

L&L, which had caught wind that an off-market deal was brewing, wanted in.

The company — which launched in 2000 and owns and manages a 6 million-square-foot New York City office portfolio, including 390 Madison Avenue and 195 Broadway — viewed it as a once-in-a-lifetime chance to get a piece of prime Park Avenue.

But the office building was not in good shape. Its electrical system was severely damaged in a fire, according to news reports, and sources said a giant extension cord was snaked up the stairs to provide power to the upper floors.

The property was home to longtime tenants such as the law firm Kaye Scholer, which had been there since 1957 and employed famed lawyers such as the late Milton Handler, a nationally recognized anti-trust expert, and Stanley Fuld, who served as the chief justice on the New York State Court of Appeals.

L&L inked a contract to buy the 33 percent stake in the fee that once belonged to the third Goelet brother. The plan was for L&L to partner with the two remaining brothers to rebuild the site in 2015 — once an existing ground lease expired with the building’s original developer.

Michael Gigliotti, the HFF broker who helped arrange $556 million in construction financing for the deal, said the circumstances were unusually favorable for L&L because leases at office buildings are generally staggered over many years. But since the building was subject to a land lease, all the tenants shared the same lease expiration date.

425 Park Avenue before construction started

“The fact that this all lined up to a specific date where you could actually knock down a Park Avenue building and build a new one?” Gigliotti said. “It’s almost unprecedented. There’s been nothing like it.”

But the deal didn’t go exactly as planned.

Once L&L signed a contract for its 33 percent stake, the brothers squeezed the firm out and bought its position — a move sources suggested was part of the Goelets’ grander plot to remove their brother all along.

The Goelets did not return multiple requests for comment.

But two years later, in 2006, the brothers put a second ground lease on the market, forcing L&L to compete against a cast of major New York real estate players such as Boston Properties, Tishman Speyer and Beacon Capital to acquire it and finally secure its chance to develop the property.

Still, L&L had a weapon up its sleeve because it already knew the family — and its quirks.

Going against the advice of attorneys and confidantes, Levinson and Lapidus made an unusual offer that included a hefty upfront payment. Despite the Goelets’ wealth, Levinson said he knew the family would want to get back the cash they paid for L&L’s 33 percent stake quickly.

The move worked and L&L won the ground lease. It signed an 84-year deal valued at $320 million that included fixed rent for the first 39 years and then a rate based on an agreed formula for the remaining 45.

But for nine years, until 2015, its lease would run alongside the original ground lease, meaning that L&L came into the deal in a so-called “sandwich position,” collecting rent from the existing tenant and then paying rent to the Goelets.

Then in 2015, L&L emerged as the only lessee and was finally free to tear down the building.

But even then it wasn’t smooth sailing.

Despite repeatedly telling Levinson that they had no desire to sell their investment, the Goelets turned around and sold their fee to TIAA-CREF for $315 million in 2011, effectively making the pension fund L&L’s landlord.

L&L has made it clear it would like to buy that position in the future.

Lehman woes

The process of building 425 Park was never going to be cheap and quick.

Lehman and L&L, who’d partnered on the site way back in 2006, began the predevelopment phase of the project early on — even though they knew they could never put shovels in the ground until after 2015. But they were actually losing money with every year they waited because the rent they were collecting on the original ground lease wasn’t enough to cover their payments to the Goelets.

What L&L hadn’t accounted for was that Lehman — which was founded in 1850 — would go belly-up. Levinson said the chances of that seemed so remote that when the firm penciled out its joint-venture agreement with the investment bank it accepted terms that were unusually favorable to a defaulting partner.

“Our lawyer looked at us and said, ‘How’d you let them get such a good provision?’” Levinson recalled. “I said, ‘Do you think we thought they were the ones more likely to go bankrupt?’”

So Lehman’s bankruptcy had the potential to leave L&L financially vulnerable.

But Levinson and Lapidus were resolved to keep the project funded. And in a strange twist, Lehman opted to continue paying its financial obligations to the project even after its bankruptcy — betting that its own creditors would see a greater return as the project got closer to the finish line.

The investment was one of only two in New York that Lehman continued to fund. The other was L&L’s 200 Fifth Avenue. Lehman’s other New York development partners were left to fend for themselves, and many defaulted on their loans and ultimately gave up their projects.

“It wasn’t like they were trying to rip our faces off by trying to buy us out at a steep discount,” said one former Lehman executive, who asked to remain anonymous, noting that L&L’s approach to the bankruptcy played into the decision to fund the project. “That routinely happened with other partners, and we rejected most, if not all, of those offers.”

Ultimately, L&L — along with Sonny Kalsi of GreenOak Real Estate and a group of wealthy investors — bought Lehman’s 90 percent stake in the property for $140 million, or about $240 per square foot. With GreenOak, L&L later brought in Tokyu Land Corporation, an affiliate of Japanese real estate firm Tokyu Fudosan Holdings, as its new equity partner.

The design conundrum

In the three years leading up to the expiration of the ground lease, L&L commissioned some of the most revered architecture firms in the world to compete to design its trophy tower. Among the finalists were starchitects such as Lord Norman Foster, the now-late Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas and Lord Richard Rogers. Meanwhile, urban designer Vishaan Chakrabarti, CBRE power broker Mary Ann Tighe, former Municipal Art Society chief Vin Cipolla and Hunter College President Jennifer Raab were all brought in to consult.

For Levinson, ensuring the perfect design became an obsession.

“He put a lot of pressure on himself,” Raab said. “He took his responsibility very seriously in creating a building that he thought could be landmarked in 30 years’ time. … He wasn’t regulated by the city, but he almost created his own mini municipal design competition, funded it and came up with an extraordinary results.”

After nine months, Foster ultimately prevailed.

Nigel Dancey of Foster & Partners said Levinson and his wife visited the firm’s London office and that he dove right in.

“He was particularly taken with our model shop,” Dancey said. “Simone said he still made models in his home. He still has a model of something he made when he was 13 years old in his office.”

With neighbors such as the Seagram Building and the newly constructed 432 Park Avenue — designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Rafael Viñoly, respectively — there was undoubtedly pressure to deliver.

Also looming was the fact that when the original building debuted, it was panned by critics who singled out its “deformed ziggurats,” attributing them to flawed zoning regulations, and likened its setbacks to an “unfortunate layer cake.”

Ironically, implementing Foster’s vision ran into more complications — also in the form of zoning codes in Midtown East.

L&L had initially placed its hopes in the proposed rezoning of the area that was being pushed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg in 2012, which would have allowed developers to build 60 percent more space without a lengthy approval process.

But when that proposal died in the City Council in 2013, L&L came up with a more innovative — and risky — solution. It found a loophole in the city’s 1961 zoning rules that allowed it to rebuild the site as it wished, without a special permit, as long as it retained at least 25 percent of the old building’s original structure.

The workaround effectively cut out the city’s Department of Planning — much to the chagrin of the then-Chair Amanda Burden.

“There was not much I could do with the building,” she told TRD. “I would have preferred they have more of an open plaza with no overhang. I’m not a fan of overhangs.”

For his part, Levinson claimed that Burden never responded to Foster’s attempts to contact her about the plaza. “Put that on the record,” he quipped.

But retaining the original structure has added yet another layer of complexity.

L&L executive vice president Bill Potts, who’s overseeing the project, said it would have been at least six months faster to build without the original steel.

Taking advantage of the loophole means that construction crews are demolishing only 75 percent of the core structure and that they need to refer to the building’s original (but not entirely accurate) plans from the 1950s. That has made it especially difficult for workers who need to preserve the original steel while demolishing around it.

“Even if a column is an inch away from where the drawings say it is, it throws everything off,” Potts said. “Every subcontractor on this job is saying that this is the most complicated job they’ve ever worked on.”

Levinson remains undeterred: “There were times when our construction engineers came to us and said, ‘We can’t do this,”’ he said. “The first time they said it, it was pretty frightening. Now it doesn’t bother me at all. I know they’ll figure it out.”

But Potts said that retaining the original steel has likely added more than $50 million to the project and put pressure on the company’s bottom line.

“It’s always a concern,” he said. “These types of things, we weren’t ready for some of it. The further we got along with the project the more we found out.”

Balancing the books

When L&L broke ground on the project in June, it toasted the event with a “traditional Japanese sake barrel ceremony.”

The ceremony — which was inspired by Tokyu — dates back hundreds of years to when Samurai needed strength and courage going into battle. Today it is used to mark important occasions and offer wishes of safety and success.

But Levinson does not seem to need ceremonial well-wishes. He said he’s confident the building will be profitable, despite all the snags.

According to the Lehman source, initial projections for the project assumed the rezoning would fail.

“That was always our base case,” said the source, who added that the company had enough financing to withstand construction setbacks. “We did all of our pro formas under the assumption that we would have to retain 25 percent of the leasable square footage area. Getting the rezoning would just have been an additional benefit.”

Levinson was so confident in the rents the property would command that when the developers inked a construction financing deal with Cornerstone Real Estate Advisers last year, he pushed for terms that allowed L&L to wait to market the building until construction was finished.

HFF’s Gigliotti called the request “unusual,” saying that most lenders demand some pre-leasing.

“We felt that when the building was built, that’s when we would get the highest rents,” Levinson said. “You can look at a picture, you can look at what you’re seeing on Park Avenue today, but there’s no way you can get a sense of how much of a game changer this is going to be.”

He even suggested that he would have preferred to lease Citadel less than the 200,000 square feet it took so that L&L could get higher rents.

In its renderings, the building certainly looks state-of-the-art, with its column-free offices, soaring glass common spaces and green spaces.

The property will also be the first accredited “wellness” office building in the city, with air and light quality monitored to promote better health, Levinson said. On the upper floors, ceiling heights go as high as 38 feet.

But L&L must get record-breaking rents to justify costs. Levinson declined to comment on the rents he’s expecting to achieve.

Brokers say the building will join a small cadre of ultra-luxury office towers, including the GM Building and 9 West 57th Street. But since it’s basically new it could have an edge over its competitors.

Still, not all top-echelon buildings are fully occupied.

According to a Fitch ratings report, 9 West 57th Street was just 63.5 percent full in September. That’s well below the Plaza District’s 90.1 percent occupancy.

But the report noted that the landlord, Sheldon Solow, is “very discerning” in selecting tenants.

“The sponsor prefers to leave space vacant and wait for the preferred type of tenant at the rent level the property has been able to maintain,” the report said.

Savills Montana said, however, that even in a shifting office market that is seeing an uptick in supply, top-shelf buildings still see strong demand. Plus, he said, Levinson cannot be counted out.

“David is a difficult guy to bet against because he has been successful so many times,” Montana said. “This will be the pinnacle of everything that David has ever learned.”

Additional reporting by Gabrielle Paluch

Correction: In a previous version of this story, The Real Deal in correctly identified the date of the 425 Park Avenue ground breaking. It was June 2015. The design competition for the building also took place over three years.