Just after 5 p.m. on a recent Wednesday, Linda and Harry Macklowe packed up to leave the Tribeca courtroom where, for the previous seven hours, paid experts had testified in their $2 billion divorce.

Linda exited first. Steeling herself for the tabloid photographer lying in wait, she stretched her lips into a wide, static smile. Harry — known to regale reporters with “take my wife”-style jokes — hung back, tapping away on his phone.

“Asshole,” Linda muttered as she walked by him.

Incensed, his mouth agape, Harry said: “Did the press hear that?”

The following day, he struck back from the stand. In his telling, the storied 13-million-square-foot Macklowe property empire was a product of one person’s chutzpah and vision: his.

“Your wife testified that she helped you find architects. Is that true?” Peter Bronstein, his lead attorney, asked.

“I couldn’t connect that at all,” Harry replied.

Did she entertain clients?

“I searched my mind for that one, and I didn’t have any recollection.”

Did she contribute design ideas?

“Husbands and wives talk, but as far as ideas, I don’t know what that means.”

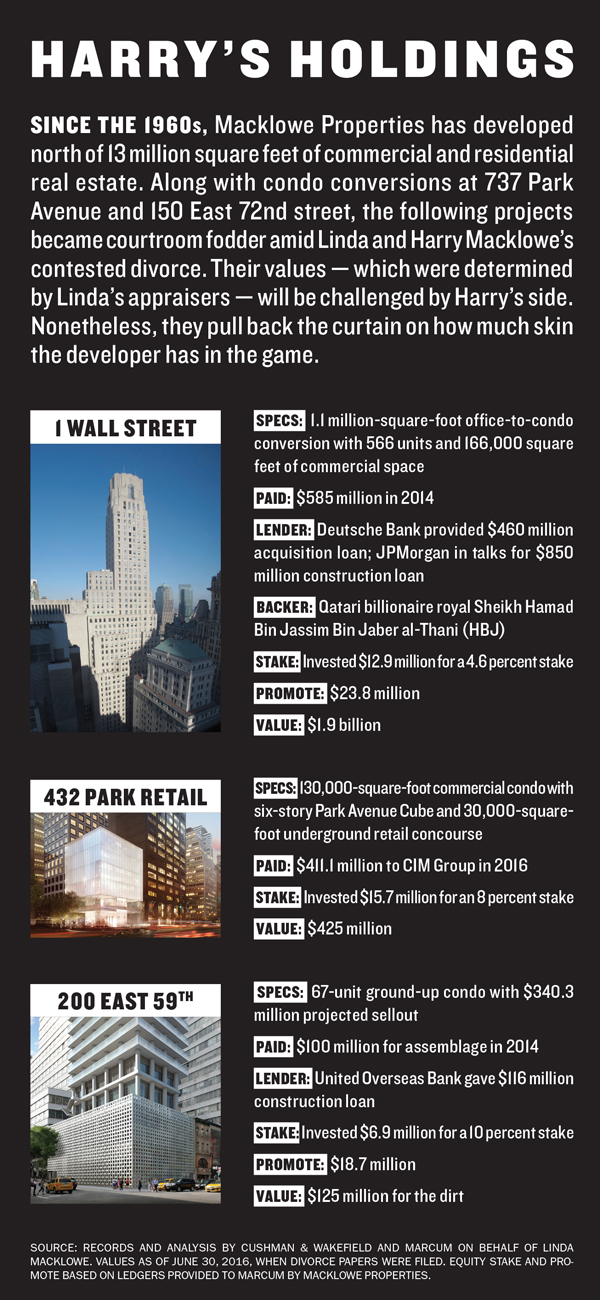

Harry Macklowe has played dice with the Manhattan skyline for decades. It’s a well-worn narrative by now: The pigheaded developer who infamously razed Times Square dwellings in the dead of night, the gambler who lost his beloved GM Building along with a $7 billion office portfolio yet clawed his way back into the pantheon, the aesthete with a Helmsley-esque devotion to his properties. With 432 Park Avenue, his legacy was secure, and with 1 Wall Street and a new mystery office project, the 80-year-old was set to end his career with a flourish. But the divorce, set off at least in part by Harry’s affair with a much younger woman, threatens to slash a fortune built over half a century. And since Harry remains active in the market, his liquidity and net worth are of interest to his lenders and partners, and to anyone looking to buy in a Macklowe project.

Justice Laura Drager, the judge handling the ongoing trial, has promised to split the Macklowes’ holdings 50-50. But what Harry is worth, and what Linda is owed, is a matter of fiery debate. It’s Solomon splitting the baby, real estate edition.

“The only way these folks can possibly work out getting those items that are near and dear to their heart is by them working it out,” Drager said from the bench. “You want this court to approach things with a scalpel, and this court doesn’t have the time and resources to do that.”

Michael Stutman, a divorce attorney who’s not involved in the case, agreed. “The judge doesn’t have a scalpel,” he said. “She has a chainsaw.”

II: The crucible

Around 8:30 each morning, a phalanx of lawyers heads into 71 Thomas Street, a limestone-and-brick building at the corner of West Broadway.

Clerks from Linda’s team lug over 30 boxes of case files that are loaded onto dollies and wheeled into Room 305.

Linda waits in a small conference room for the clerk’s announcement: “All parties for Macklowe!”

Harry is typically among the last to arrive. Impeccably dressed in a dark suit and noiseless loafers, he carries an orange-and-white Macklowe Properties tote and a Starbucks shopping bag with three large coffees. Husband and wife sit on opposite ends of a long wooden table.

Drager used to preside over criminal cases, and once ran the rackets bureau at the Brooklyn district attorney’s office.

“She knows what kind of crucible the courtroom is,” said Stutman, who’s argued before Drager. “She knows how to expedite cases through the system.”

In 2014, Drager was assigned another high-profile split: former governor Eliot Spitzer and Silda Wall.

In that case, she took pains to keep the proceedings out of the tabloids. Spitzer and Wall reportedly never had to show up in court.

The Macklowes, however, received no special treatment, no veil from public view. “Your personal lives, your business, your assets, everything will be displayed for everyone to see,” Drager said in late August. The trial, she warned, was “not going to be a pleasant experience.”

According to Harry, the couple’s assets are valued at $1.3 billion. He’s pegged his personal net worth, however, at negative $400 million, largely as a result of deferred capital gains from the $2.8 billion sale of the GM Building in 2008.

John Teitler, Linda’s lead lawyer, towers over his client, a diminutive figure even in kitten heels. “This is a case study in divorce accounting 101,” he said during opening remarks on Sept. 6, pacing in clunky loafers. “Mr. Macklowe himself knows these types of [capital] gains are never actually realized by real estate developers.”

Harry’s lawyer, Bronstein — who also represented the Macklowes’ daughter, Liz, in her split from real estate scion Kent Swig — dismissed Teitler’s remarks as “divorced from reality.”

Later, Harry testified that after selling the GM Building, he was subject to getting taxed on gains of roughly $900 million. Though he negotiated a “tax protection plan” with buyer Boston Properties, the shield lifts this year, he said.

“I tried with my attorneys to get a written document extending the protection, but I wasn’t able to.”

If Linda takes half the assets, it’s only fair that she take on some of the liability, argued Bronstein, a portly 70-something with curly gray hair. “Mr. Macklowe is trying to get his business back on its feet,” he said. “He’s had to borrow money, get pieces of deals.”

III: Matrimonial math

Since 1980, New York state has treated marriage as an economic partnership. In contested divorces, marital assets — defined as any property acquired during the marriage — are divvied up based on each spouse’s contribution to the union. Even when both sides agree to a 50-50 split, the court has a good bit of discretion, tasked with valuing each asset and ensuring both parties get their fair share.

“It’s really mathematics; it’s a numbers game,” said Ira Garr, a lawyer who represented Rupert Murdoch in his 2013 divorce from Wendi Deng. “If you’re on the giver side, you want [the discount on those values] to be as high as possible. If you’re the wife, you say, ‘No, no, no, he controls the whole building.”

In the case of the Macklowes — who have no prenup — many of the marital assets are in Linda’s name. After losing the GM Building, Harry reportedly transferred several properties to her to stave off creditors. Before the divorce trial kicked off, the developer’s camp signaled a desire to settle out of court. “It’s not a case that should be tried,” one of Harry’s lawyers, Dan Rottenstreich, said in June to the New York Post, which reported that the developer had offered Linda $1 billion to walk away. Linda disputed that claim.

“I have not seen that offer nor anything else like it,” she said. “If that is the offer, I will take it and we will be done tomorrow.”

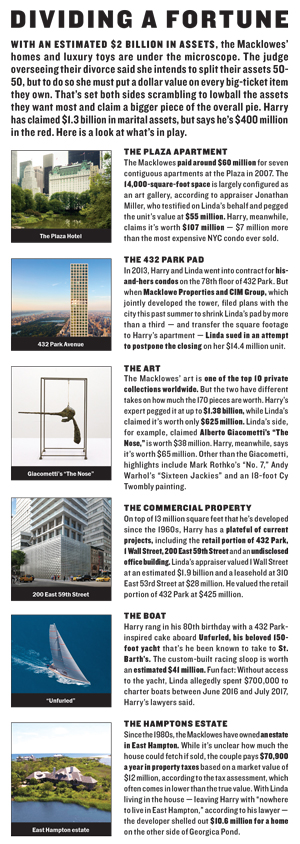

It’s hard to parse fact from fiction in the trial. Is the couple’s renowned art collection worth $625 million, or $1.4 billion? The lavish Plaza spread they shared worth $55 million, or $107 million?

Both sides are trying to water down their own assets in order to claim a bigger slice of the other’s. In Harry’s case, that means painting his real estate empire as fragile and at risk.

The developer’s 65-unit condo at 200 East 59th Street has sold just three units after nearly a year, Bronstein said. His office-to-condo conversion at 1 Wall may be a dud, as heavy security at the nearby New York Stock Exchange could hinder easy access. And 432 Park’s underground retail concourse is a victim of the soft market.

1 Wall — where Harry is still negotiating a construction loan with JPMorgan Chase — may be the most vulnerable. Sources said other developers passed on the site after failing to see how the numbers worked. In May, Harry scrapped plans for a rental component at the tower, which will instead have nearly 600 condos. His backer on the project, and on 432 Park’s retail, is Sheikh Hamad Bin Jassim Bin Jaber al-Thani, a billionaire Qatari royal.

“I’d be super nervous,” one brokerage head said of 1 Wall. “You’ll see sponsor units sitting in the Macklowe sales gallery for a decade.”

In mid-September, Cushman & Wakefield’s John Feeney, hired by Linda’s team, testified that Harry is doing just fine. According to Feeney, when the divorce papers were filed last June, 432 Park was worth $2.4 billion, and 200 East 59th was on track to see gross proceeds of $414.5 million.

Harry sat expressionless throughout the testimony, occasionally sketching in a notepad but never looking at Linda.

It’s notoriously difficult to know how much of a project a developer actually owns, but the divorce is laying bare Harry’s stakes.

According to testimony by Mark Harrison, an accountant at Marcum hired by Linda, Harry invested $15.7 million for an 8 percent stake in 432 Park’s retail, which he bought from CIM Group for $411.1 million in 2016. At 200 East 59th, Harry invested $6.9 million for a 10 percent stake, and his gross proceeds are estimated to be $18.7 million. At 1 Wall, he has a 4.6 percent stake and is expected to earn a $23.8 million promote.

Harrison, whose firm earned $1.3 million for its work in the case, said the couple’s joint tax write-off between 2009 and 2015 was “over $460 million.” The “net operating loss” on Harry’s personal tax returns averaged $64 million during that time, Harrison said. He projected Harry’s income at $55 million a year between 2017 and 2021.

Drager’s frustration has grown throughout the trial. In October, she lashed out after Bronstein introduced a summary of Linda’s bank account, which the other side said it had just received. The summary showed $102 million in deposits between 2007 and 2016 — including nearly $68 million from the sale of art that Harry claimed he was unaware of.

“Okay, we’ll spend more time and money,” Drager said. “I know you folks have a lot of money. It’s your money to spend, and you’re choosing to spend it on this litigation. I’m taking a short break.”

IV: Shaken, not stirred

A few weeks into the trial, Harry complained about The Real Deal’s coverage of the divorce. It’s tabloid fodder, he said, not a real estate story.

It’s true the city’s tabloids have been all over it. The Post termed Harry a “lusty long-in-the-tooth Lothario.” The paper revealed that Patricia Landeau, the 62-year-old Frenchwoman who Harry has said he intends to marry, has quietly lived for the past two years at Harry’s luxury condo conversion at 737 Park Avenue.

“I am not a French kept girlfriend,” Landeau, president of the French Friends of the Israel Museum, told the outlet.

But as a developer with several ongoing projects, Harry’s liquidity along with his net worth — which is now in jeopardy of being halved — are very much tied to his loan covenants. And those in the business are closely watching to see how it all unfolds.

On June 7, Bloomberg reported that JPMorgan agreed to lend Harry $850 million to move forward with 1 Wall, a coup in a tight construction lending market. Days later, his divorce hit Page Six.

“To the extent that [Linda’s] able to get business assets, or vacuum up all his cash, he has a problem,” said Joshua Stein, a real estate attorney who is not involved in the case. “Even if he doesn’t trip up the financial standards and guarantees [in loan documents], certainly the construction lenders are relying on him to cover cost overruns. He’s going to emerge from this weaker than he was before.”

Others don’t see the divorce as posing much of a problem.

Dealing with Harry, they said, has always come with a side serving of drama — Eastern Consolidated Chairman Peter Hauspurg once said, “it can be a charming experience, and it can be like a trip to the dentist without anesthesia” — and lenders and partners are likely to look the other way.

“Banks lend money to people who have way less than what Harry will have,” one top finance broker said.

“I would think a lender would have to be very reluctant to claim a technical breach or try and create a default,” said the Carlton Group’s Howard Michaels, who helped Harry raise equity for the GM Building deal. “Because frankly, there aren’t that many people who can do what he does.”

The success of 432 Park bought Harry a lot of get-out-of-jail-free cards, sources said.

“How many developers in town can say they built a 432 Park?” said a broker who’s worked with him but requested anonymity.

In late 2016, Singapore’s United Overseas Bank — which had already provided a $65 million acquisition loan — gave Harry a $116 million construction loan for 200 East 59th.

Joseph Sarcinella, an attorney who represents UOB on non-Macklowe deals, acknowledged that the divorce has become fodder for elevator chitchat. But he said he doubts it will impact future loans.

“The deal itself needs to stand on its own. His liquidity is only a backstop for any guarantee,” Sarcinella said. “If there are cost overruns and he needs the cash, he’ll be able to draw credit lines to satisfy liquidity or any obligations under the guarantee.”

V: Apartment therapy

After a forensic analysis of Macklowe Properties’ holdings, the court turned to Linda’s apartment at the Plaza. Harry’s appraiser, Metropolitan Valuation Services, claimed that it’s worth $107 million. But Jonathan Miller, hired by Linda’s team, argued it’s closer to $55 million.

The Macklowes paid around $60 million in 2007 for the spread, seven contiguous units spanning a combined 14,000 square feet. The corner unit has 54 windows and “the largest master bedroom I’ve ever seen,” testified Miller, who has done 8,000 appraisals since 1986. “It’s a wide open, almost loft-like space that looks to me like an art gallery.”

Values at the Plaza, Miller argued, haven’t stood the test of time, particularly in a market where there’s a perceived oversupply of apartments priced at $5 million and up. Harry’s appraiser, he said, is “plussing up” numbers to get to the $107 million tag.

“Their assumption is about $7 million more than the all-time record at One57 on the [90th] floor versus a seventh-floor apartment,” he said.

In his cross-examination, Rottenstreich, who also represented the estranged wife of Anthony Scaramucci in a paternity dispute, pointed out a clerical error in Miller’s appraisal. Drager interrupted to ask where Metropolitan obtained certain statistics.

The data, it turns out, came from Miller’s monthly market reports.

There’s another pricey piece of real estate the Macklowes are fighting over — his-and-hers apartments at 432 Park.

In September, Linda filed a suit accusing Harry of quietly submitting plans to downsize her apartment to a one-bedroom, and then trying to force her to close on the $14.4 million unit. According to the suit, Harry’s adjacent apartment would eat up the square footage lopped off of Linda’s pad.

“We shouldn’t have to close when they’re playing dirty,” said another of Linda’s lawyers, Adam Leitman Bailey, who tore his navy pinstriped suit during his animated courtroom performance. But Ronald Greenberg, a lawyer for the 432 Park developers, said Linda was using the apartment as a pawn in the divorce. The condo is ready except for a few “punch list” items, he said.

As part of the trial, Linda’s expenses were also scrutinized: She started with $37 million in cash in June 2016 and withdrew $10 million by July 2017, spending $7 million on legal fees, $2.7 million on a painting and $700,000 to charter yachts over the summer.

“That’s my personal life,” she testified. “I don’t think it’s any of your business.”

Linda brought up the $10 million East Hampton estate that Harry and Landeau purchased over the summer. “He bought a country house!”

“He had nowhere to live,” Bronstein replied.

“What do you mean, nowhere to live?” Linda snapped.

“Well, nowhere to live in East Hampton.”

VI: Harry takes the stand

Harry Macklowe was ready to tell his story.

It was shortly after 3 p.m. on Oct. 19 — six weeks since the trial started. He stated his name and date of birth in a quiet voice — so quiet, in fact, that Drager asked him to speak up. Linda remarked that she’s never heard him so soft-spoken.

“There are very few firsts left,” he responded, flashing a smile.

Linda Burg and Harry Macklowe were married on Jan. 4, 1959, at the Savoy-Plaza Hotel, which was razed in 1965 to make way for the GM Building.

Neither came from money. Linda, the daughter of an internist in the Bronx, was 20 and an editorial assistant at Doubleday. Harry, the son of a garment executive, was a 21-year-old college dropout from New Rochelle, N.Y., working as a trainee at a Madison Avenue advertising firm.

He got interested in real estate when the newlyweds rented their first apartment, a duplex garden unit in Brooklyn. After a stint working for Julien Studley, he launched his own commercial leasing firm with longtime broker Mel Wolf. “I ran parallel careers, running a brokerage company and at the same time looking for investments,” he said.

The Macklowes’ relationship was “often compared to an Edward Albee play,” according to Vicky Ward’s book, “The Liar’s Ball.” The Macklowes, Ward wrote, were known to disparage each other “forcibly and publicly,” yet were also inseparable.

But things got worse after Harry lost the GM Building.

Linda was “openly livid about the [$1 billion] personal guarantee” Harry gave Fortress Investment Group, which provided a bridge loan for the property in 2008. Michael Fascitelli, then at Vornado Realty Trust, recalled Linda tearfully telling him the family and business couldn’t endure more risk. “In the end, Linda called the shots,” Fascitelli told Ward.

A decade later, Harry testified that he had the vision all these years; he created the deals; he built the buildings; he saved their fortune when creditors came calling.

“My wife was my wife, but she played no role in assembling the buildings,” he said, avoiding Linda’s gaze as she threw her hands up in disgust.

Drager pushed to understand Linda’s level of involvement in the business. Several times during Harry’s testimony, she asked him how Linda reacted when he told her the GM Building would have to be sold.

“What did she say?” Drager asked. “Was there a discussion of any assets to be sold instead of that one?”

“All the other assets were looked at,” Harry replied mournfully. “I did what I had to do to get funds to pay my obligations. It should be noted that it was unfortunate, but that’s what it was.”

Bronstein asked about how Harry and Linda’s relationship changed at that time.

“It’s a leading question, but you can answer,” Drager said.

Harry obliged. “My relationship with my wife was not a good one, or a happy one,” he said. After losing his long-coveted trophy, he was depressed. “What I wanted was the support of my family and my wife, and that absolutely was not there.” (Harry’s relationship with his son, Billy, now the CEO of William Macklowe Company, disintegrated as they tried to salvage their holdings in 2008. Last November, Harry filed a $300 million suit alleging that Billy had usurped control of his websites.)

Harry described the public humiliation he felt as Linda called him a “fool, crazy, an old man” in front of friends and peers.

Though the Macklowes were forced to give up several prime properties, their art collection, which has notable works by Warhol, Picasso, Rothko and de Kooning, survived unscathed. How much it’s worth is now one of the key points being debated.

Christopher Gaillard, the appraiser hired by Linda, pegged it at $625 million. But Harry’s appraiser, Elizabeth von Habsburg, said the collection is worth at least $828 million, and up to $1.38 billion if sold as a package.

“The Macklowe name is not just known as a real estate name,” von Habsburg said. It “is one of the top 10 collections worldwide in private hands.”

Though it’s controlled by Linda, Harry testified that he paid for every piece. Afterward, Harry asked a courtroom sketch artist, Christine Cornell, whether she was related to Surrealist Joseph Cornell. The developer, who seemed pleased at her portrayal of him, couldn’t resist a final joke at Linda’s expense. “I know who isn’t going to buy it.”