This past spring, Stribling & Associates broker Charlotte Van Doren landed an exclusive on a four-bedroom condo on East 57th Street and listed it for just shy of $5 million. Within 48 hours, buyers were making offers, and six days after going live, the property went into contract for $200,000 over the ask.

But now a very different scenario is playing out in the same building — with the same broker, just one flight up. Encouraged by their neighbor’s success, the owner of an identical apartment set its price at an aggressive $5.6 million. After several weeks on the market, however, there have been few showings and no offers, Van Doren said.

Unfortunately for brokers working in Manhattan’s residential luxury market — especially on the very high end — that story is not unique. While optimism in the sector was strong during the “frothy” spring market, sales are now dragging out and brokers are decidedly more anxious.

“[Brokers] are talking about how hard it is to get a deal done in a market that many perceive is declining,” said Douglas Elliman’s Sabrina Saltiel, who’s marketing an $82 million apartment at 432 Park Avenue. “Getting people to feel secure enough to pull the trigger and not feel they are catching a falling knife is difficult.”

After a rocky 2016, the industry had high hopes for 2017. And the start of the year did indeed seem promising. But things began changing just after the year’s midpoint.

The luxury market logged its worst summer in terms of the number of contracts signed since 2012, according to data from Olshan Realty. While luxury contracts are now starting to edge back up, the sector is still seeing lingering properties, slow absorption and a glut of new product that is getting worse — not better.

Sources said that despite a recent spate of high-profile deals — a contract on Grammy Award winner Sting’s $50 million duplex at 15 Central Park West and the $51 million penthouse contract at Ian Schrager’s 160 Leroy Street, to name a few — the challenges for the high-end market are very real, especially for new developments.

Simply put, Van Doren said: “Buyers have a lot of choices. They feel a sense of control.”

Contract contraction

At this time last year, brokers were blaming the election for the lackluster number of contracts being inked.

An internal survey at the Corcoran Group in the lead-up to the presidential election found that around 40 percent of the firm’s brokers had a client waiting until after the election to move on a purchase.

But now — exactly one year post-election — things are not looking up.

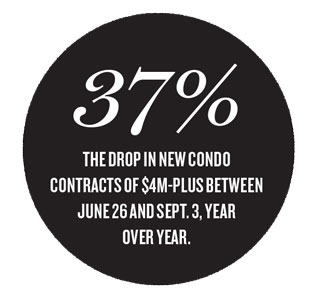

Between June 26 and Sept. 3, the number of contracts priced at $4 million-plus declined by 14 percent, to 158, from the same time last year, Olshan Realty found. That drop was even more pronounced for new condo contracts of $4 million-plus. Those fell by a massive 37 percent year over year.

Stribling’s Kirk Henckels said the $5 million-plus category is “basically treading water.”

“[For buyers] it feels like the apocalypse. You have Trump, North Korea and natural disasters … who knows what the heck is going on,” he said.

Elliman’s Richard Steinberg — who put a $16.3 million co-op at 550 Park Avenue into contract last month after a year on the market and several price reductions — said it’s taking “twice as long to get a deal signed.”

“People are nervous, with the social climate the way it is,” he said. “I used to be able to get contracts signed in a week.”

Meanwhile, Rutenberg NYC’s Jeffrey Fields, who represented the buyer in a deal for a condo asking $79 million at Zeckendorf Development’s 520 Park Avenue earlier this year, said sales are happening in some parts of the borough but not others.

“If you look at prime Soho, the only ground-up new construction is 150 Wooster Street,” he said. But in Midtown, the market is “extremely slow due to the glut of luxury inventory.”

Despite the recent doom and gloom, Donna Olshan, founder of Olshan Realty, said contracts are starting to return to healthy levels.

“The benchmark for stability is 20 or more contracts signed in a week,” she said. “If we fall consistently below 20 contracts in prime selling season, that’s not good.”

The Corcoran Group’s Vickey Barron said there are definitely brokers who “will panic when data comes out that is worrisome.”

But, she said, she’s not one of them: “I tend to … focus on the big picture. If you worry about every headline, you wouldn’t get out of bed each day.”

Nonetheless, however it’s sliced and diced, brokers are feeling the standoff between buyers and sellers in their commission checks.

“The stalemate status hurts brokers,” said CORE’s Doron Zwickel, who has been marketing an $8 million penthouse at the Izaki Group Investments-developed 93 Worth Street since 2015. “Brokers do deals when the market is hot or when it’s weak; [they] don’t make money when there are stalemates.”

Inventory issues

For those who thought Manhattan’s stubborn new development inventory issue was subsiding, think again. In fact, the situation is worsening.

By the end of this year, there will be 6,300 unsold new units in Manhattan, according to data from appraisal firm Miller Samuel. That figure includes shadow inventory — condos that are intentionally being held off the market. The firm estimates it would take 3.3 years to chew through that many units at the current pace of sales.

Next year, the market is expected to add another 3,000 units, with absorption time also increasing, to 3.9 years.

That stat should have brokers fretting, sources said.

Miller Samuel CEO Jonathan Miller said a healthy absorption rate for the New York market is around one to two years. “The market clearly has excess supply,” he said. “The excess is more heavily weighted to the higher end than the lower end.”

Miller Samuel CEO Jonathan Miller said a healthy absorption rate for the New York market is around one to two years. “The market clearly has excess supply,” he said. “The excess is more heavily weighted to the higher end than the lower end.”

Indeed, an analysis of listings on On-Line Residential by The Real Deal in late September found 355 Manhattan units — both new development and resale — being marketed for $10 million or more. In the last five years, between 170 and 300 units in that price bracket have sold annually, according to a TRD analysis of property records. While those might seem like good odds for a seller, that number doesn’t include all the shadow units waiting in the wings.

In general, Manhattan buyers are very much aware that their choices are piling up.

“Right now, there’s so much in the pipeline,” Elliman’s Saltiel said. “The developers who recognize that are making deals. The buyer has to feel like they are getting value.”

CORE’s Zwickel said the realities of the market have made it harder for brokers.

“I find myself doing a lot more of the legwork than before,” he said. “I have to be a lot more visible than previous years, so as not to miss out on opportunities.”

However, while inventory in Manhattan’s new development market is growing, the supply of listed resale units in the borough has shrunk. In the third quarter, Manhattan resale inventory dropped 3 percent from the previous quarter, according to Miller Samuel. That’s already proved to be a good thing for pricing among resales. And while Brooklyn has a rental glut— with nearly 3,000 new units flooding the market in the third quarter — the for-sale market in the borough saw inventory fall 30 percent year over year during that time. That has translated into more demand than supply and an absorption rate that’s moving at a “blistering pace” of 1.9 months, according to Miller.

“The luxury stuff is really highly aggressive [in terms of] pricing at times,” said Citi Habitats’ David Maundrell, referring to the $1,700 to $2,000-per-square foot market in the borough. “It does take a bit longer, but it is selling.”

Plummeting prices

If closing prices were looking strong for a while, there was a good (albeit under-the-radar) reason for it: They were being bolstered by pricey deals signed a few years back that were finally closing.

But in the third quarter, the market got hit with a disturbing reality check.

The average closing price in new developments dropped 27 percent year over year to $4.3 million. Miller attributed the decrease largely to the fact that those “legacy closings” — or closings on deals signed between 2013 and 2015 at properties like 432 Park and 150 Charles Street — are drying up.

“Developers weren’t giving discounts when they signed contracts in 2013 and 2014,” he said. “Since then, they have been.”

In addition, while more than 15 percent of resales closed above ask, not one of the new development units that closed in 2017’s third quarter sold for above its listing price, Miller’s figures show.

“Aspirational pricing will not do in this market,” said Elliman’s Bruce Ehrmann, adding that he’s seen a drop in the number of people coming to showings in the past few months. “If someone wants to run a flag up the pole to see if someone salutes, then that’s fine, but if someone wants to sell a property, it has to be priced for this market.”

Miller estimates that condo buyers at high-end new developments are signing contracts priced an average of between 15 and 20 percent lower than buyers were at the peak of the luxury market in 2014.

And there have been plenty of recent examples of the sliding high-end market. In August, the former CEO of cosmetics company Avon, Andrea Jung, sold a five-bedroom duplex at Toll Brothers’ 1110 Park Avenue for $17 million — a $600,000 loss on what she paid a little over a year earlier.

Sources said some developers who are refusing to cut prices are doing so at their own peril.

“It’s a lot slower than we all want it to be,” said Elliman’s Kirk Rundhaug, who was speaking generally but recently took over marketing at Atlas Capital Group’s 42 Crosby and is also marketing 160 Leroy. “I think sponsors get overzealous if you sell so many units in a building, and they want to raise the prices.”

That’s not to say that some brokers aren’t getting deals done.

Sotheby’s International Realty’s Nikki Field said that at the 48-unit condo 212 Fifth Avenue — a project by Madison Equities, Thor Equities and Building and Land Technology — they are “cranking” out contracts.

But some say developers generally need to lower their expectations.

“Most people have overpriced their properties. I cannot underscore enough how the developers are a big part of that problem,” said Olshan. “They are hung up on their own delusions, or they are hamstrung by equity and banks.”

Lingering listings

Time, as the saying goes, is money. And right now, it’s taking more time to sell a luxury Manhattan property than many brokers are comfortable with.

From late August to mid-October, the average number of days it took to sell a $4 million-plus Manhattan property jumped around 30 percent, to 447, year over year.

“This is one of the factors that give the brokers the feeling that the market is slowing,” said Olshan. “It’s hard not to notice that so many properties are sitting unsold for such lengthy periods of time. It’s a worrying statistic.”

Warburg Realty’s Jason Haber, who is marketing a townhouse at 113 East Second Street for $10.5 million, invoked an analogy to the movie “Frozen” in discussing the market.

“It’s not like Queen Elsa has gone through and frozen the luxury market,” he said. “[But] days on the market is going up … You have to notify the sellers that this could take a long time.”

Michele Kleier, of Kleier Residential, said the luxury market has lost the “frothiness” it was seeing this past spring.

“The market was unbelievable in May, June and July … in August and September it calmed down,” she said, noting that she has three Upper East Side listings priced between $5 million and $9 million that have had showings but no accepted offers.

The fact that properties are sitting on the market means brokers now need to do more (and spend more) to get a listing sold, said Tyler Whitman, who heads a four-person team at the startup lead-generation brokerage Triplemint.

“In the old days, we could slap a listing on StreetEasy — that’s not today’s market,” he said. “The main complaints that I hear from top brokers is that ‘our job is so expensive now.’ It’s not; it’s just that we got away with spending nothing for so long.”