UPDATED, Nov. 13, 1:20 p.m.: For a giddy instant in 2013, an obscure investor rose to new heights after paying $56 million for a majority stake in a joint-venture project to build the tallest residential tower in the Western Hemisphere.

It’s been downhill ever since for Richard Bianco and his firm, AmBase Corporation, as well as the ambitious 111 West 57th Street spire and its two sponsors — Michael Stern’s JDS Development and Kevin Maloney’s Property Markets Group.

As of mid-October, the steel frame of the Billionaires’ Row development, above the landmarked Steinway building, stood at roughly 500 feet, on its way to a planned 1,438-foot-pinnacle. But court records, regulatory filings and interviews with sources close to the project and its partners reveal a maelstrom of anxiety and mistrust and a heap of equity, debt and legal costs.

The tower fell into foreclosure in late August, the culmination of a bizarre legal drama that has left AmBase fighting for its survival and the project’s future on shaky ground.

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” said Stephen Meister, one of the attorneys representing the small Connecticut-based holding company. “I think it’s an outrage.”

And potential buyers of the 60 condos that were once expected to bring in a total of $1.45 billion have likely taken notice. “Top-tier developers don’t usually get into squabbles like this,” said Donna Olshan, president of the eponymous residential brokerage. “Every buyer is on Google, and they’re going to be looking this up.”

Michael Stern, left, and Kevin Maloney, right. AmBase’s Richard Bianco is not depicted.

Bianco alleges that Stern and Maloney conspired with the mezzanine lender behind the foreclosure to cheat AmBase out of its stake. But the developers deny those accusations and claim AmBase is the real culprit — a financial hostage-taker holding the project for ransom. Bianco and Stern declined to comment for this story, while Maloney described the dispute as “very unfortunate.”

Now, with an appeal against the foreclosure underway, the project’s fate increasingly seems to hinge on Bianco. While the roughly 69-year-old executive is short on experience as a developer, he stands tall as a litigant. His seminal triumph came in August 2012, when he walked away from a 20-year legal wrangle with the federal government over a troubled asset with a $180.6 million settlement. Once again, AmBase may be fighting for its existence: 111 West 57th Street is listed as the firm’s only asset, apart from a small office building in Greenwich, Connecticut.

“Dick [Bianco] is like a dog on a meat bone when he feels his shareholders’ rights have been violated,” said David Thompson of Cooper & Kirk, another AmBase attorney, who has known Bianco for more than two decades. “If I had to describe him in one word, it’s ‘tenacious.’”

Mysterious moneymen

In March 2013, JDS and PMG went into contract to buy the land under the Steinway building — one of the last steps in a series of deals that would give them control of the prime development site. There they planned to put up a tower 433 feet taller than Gary Barnett’s One57 down the street, where a penthouse had recently sold for over $100 million.

There was just one problem: Stern, the soft-spoken real estate prodigy, and Maloney, the hard-knuckled development veteran, didn’t have the cash to seal the deal.

They lined up Andy Ruhan, a media-shy British entrepreneur and motor racer, as their primary backer, sources told The Real Deal. But by June of that year, just a few weeks before the closing, Ruhan had significantly lowered his offer. He would still purchase a stake in the project, but less than what the developers needed, and Stern and Maloney had to find another investor fast.

That’s when Mark Walsh and Masood Bhatti — two former Lehman Brothers executives who had joined the real estate fund manager Silverpeak — introduced them to Bianco. The savvy but relatively unknown investor had recently come into a large sum of cash that he needed to put to work.

In the end, AmBase’s longtime CEO agreed to buy a 59 percent stake in the joint venture. Ruhan and his frequent business partner, Arthur Becker, took a 26.3 percent stake in the project, according to several sources, and Stern and Maloney held onto the remaining 14.7 percent. (Becker denied that Ruhan is an investor in 111 West 57th, claiming that his equity “comes from various offshore trusts,” though he declined to say who controls them. Ruhan did not return requests for comment.)

In the end, AmBase’s longtime CEO agreed to buy a 59 percent stake in the joint venture. Ruhan and his frequent business partner, Arthur Becker, took a 26.3 percent stake in the project, according to several sources, and Stern and Maloney held onto the remaining 14.7 percent. (Becker denied that Ruhan is an investor in 111 West 57th, claiming that his equity “comes from various offshore trusts,” though he declined to say who controls them. Ruhan did not return requests for comment.)

While Bianco’s name rang no bells in New York real estate circles, news of his investment fit a pattern. It came at a time when obscure overseas investors pumped huge sums into development after development, with no questions asked and often little real estate experience needed.

“Maybe [Stern and Maloney] thought they had dumb money,” said one former AmBase investor on the condition of anonymity.

AmBase’s big win

The publicly traded holding company, based in Greenwich, started as the Home Group, an insurance firm founded in 1853 that changed its name to AmBase in 1989. Drowning in debt from a long string of acquisitions, the company liquidated most of its assets in 1991. But one major, troubled holding was left over: New Jersey-based Carteret Savings Bank, which AmBase acquired in 1987.

Carteret had snapped up several struggling lenders during the savings and loan crisis. It did so under a federal rule that allowed healthy buyers to count any “supervisory goodwill” they bought toward their regulatory capital — the equity buffer required as an insurance against losses. When Congress abruptly ended that perk in 1989, Carteret’s capital plunged 50 percent.

It then struggled to raise cash for the next three years until time ran out in 1992 and the federal government seized the bank. That left Bianco — AmBase’s then-fledgling CEO and a former managing director at the blue-chip investment bank Dillon, Read & Co. — to salvage what he could. He led the company into court, accusing the government of breaching its contract with Carteret.

But the feds held firm, and the case dragged on for nearly two decades.

“The government’s strategy was to litigate these cases into the ground,” said another former AmBase shareholder, who snapped up shares on the cheap in the 1990s hoping for a big payday in court.

Bianco told the New York Times in October 2011 that he reckoned AmBase had spent roughly $10 million on attorneys’ fees up to that point. But a year later, his persistence paid off with the nine-digit settlement.

Bianco then doled out $87.5 million to AmBase’s shareholders — including him and his family — as a special dividend. He also collected a $13.6 million bonus for winning the settlement. The victor then had to figure out what to do with his remaining spoils, so he decided to aim nosebleed-high with 111 West 57th.

111 West 57th Street

“We were happy to have him,” Maloney told TRD. “You never go into partnerships under any circumstances where you have a bad feeling. It’s like getting married. When you see people walking down the aisle together, do you think they’re thinking, ‘Wow, I can’t wait to get out of this’?”

High-rise tensions

With no experience in development, let alone the kind needed to build an 82-story skyscraper, Bianco left the project’s day-to-day management to the two men who had the original vision.

Stern, 38, had made a fortune from a series of residential projects just like his occasional partner, Maloney, 58. The two had previously collaborated on the 24-story Walker Tower in Chelsea, a 1920s-vintage commercial property they converted to condos, where a penthouse unit fetched over $50 million in 2012. Soon after, they jointly converted a former Verizon building in Hell’s Kitchen into the Stella Tower.

Stern is also developing 9 DeKalb Avenue, the 73-story rental and condo tower in Downtown Brooklyn, in partnership with the Chetrit Group. Maloney, meanwhile, has an estimated $3 billion in properties under management in New York, Miami and Chicago.

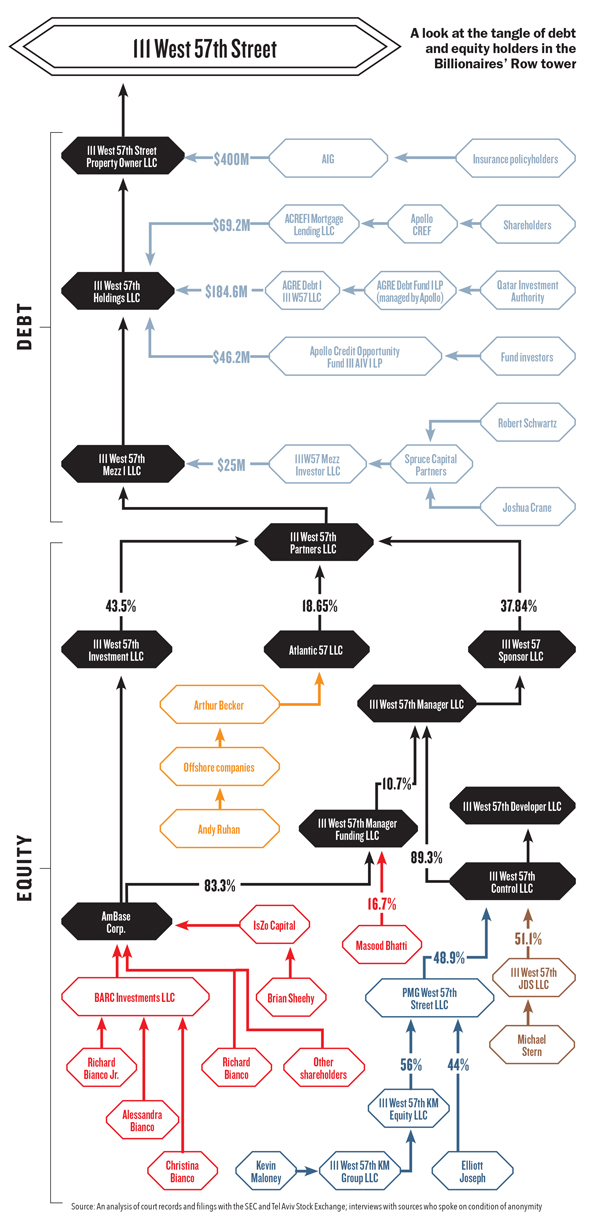

Upon signing the contact for 111 West 57th, the project’s sponsors landed a $230 million acquisition loan from Annaly Capital Management. Two years later, they took out a $400 million senior construction loan from AIG and a $325 million mezzanine loan from Apollo Global Management. Apollo then moved $200 million of the debt into a fund that manages money for the country Qatar. For the project’s partners, all signs were green.

But as the physical structure began to grow, so did the suspicion. The turning point came in March 2014, when Stern and Maloney issued a $1.8 million capital call to help fund the purchase of air rights for the tower.

With pressure mounting, AmBase hired the advisory firm Sterling Project Development that July to consult on the project and keep an eye on the investor’s partners. Meanwhile, excavation and construction around the landmarked Steinway building was proving more complex than expected, leading to delays and cost overruns that eventually totaled more than $50 million.

In less than a year, the developers made five additional capital calls — for a combined $61.8 million — to cover everything from insurance to construction costs, court filings show.

Short on cash, AmBase met the first three capital calls, as well as the last one, with the help of personal cash infusions from Bianco. It did not fully cover the fourth and fifth. The two developers covered the shortfall themselves and treated their additional contributions as “dilutive capital,” per court records. That meant every extra dollar that Stern and Maloney invested upped their stake in the project by $1.50 at the expense of Bianco’s. By mid-2015, his firm’s share had shrunk to 43.5 percent, while Stern and Maloney had expanded theirs to 37.8 percent.

Then in March 2016, Maloney told Bloomberg that the developers had decided to put the project’s condo sales on pause due to a lack of demand for ultraluxury apartments. By that point, the honeymoon had given way to open legal warfare.

Then in March 2016, Maloney told Bloomberg that the developers had decided to put the project’s condo sales on pause due to a lack of demand for ultraluxury apartments. By that point, the honeymoon had given way to open legal warfare.

AmBase filed a lawsuit against the developers the following month, alleging they had “devised a scheme to increase their ownership interest in the joint venture at the expense of AmBase … artificially driving up development expenses and then issuing unnecessary capital calls to cover the purported costs.”

Stern and Maloney’s attorneys filed a motion to dismiss the complaint, claiming AmBase failed to meet its funding obligations and the developers “saved the project from ruin.”

But relations between Stern and Maloney had also hit hard times, with Maloney accusing Stern of usurping too much credit for the partnership’s successes. A source close to the developers acknowledged that the two aren’t “best buds” today but said they have a “productive and respectful working relationship.”

Desperate measures

With AmBase balking on further cash contributions as its case progressed, the developers tried to pay for the cost overruns by lining up additional investors.

In December, they struck a deal with the Boston hedge fund Baupost Group for a $100 million mezz loan, which carried a floating interest rate that amounted to roughly 17 percent in the first year, per court records and a source familiar with the arrangement.

But Bianco tightened the screws, refusing to okay the deal and blocking the money from coming in. Instead, he moved to exercise a provision in the joint-venture agreement that required the developers to buy out his share once construction costs rise beyond a certain point. AmBase alleged in court records that it’s owed $136 million under the so-called equity put right — more than double the firm’s original investment.

The developers claimed they never submitted an official budget that could have triggered such a demand. Stern and Maloney accused Bianco’s outfit of shirking its responsibility by failing to pay capital calls and compounding the damage by barring an outside cash infusion. In a notably contentious court filing from January 2017, the developers accused AmBase of withholding consent unless they “agreed to pay defendants a sum of money to which defendants were not contractually entitled.”

Without the full cash infusion the project needed, the $325 million mezzanine loan for 111 West 57th had fallen out of balance by January, raising the possibility of default. But the developers signed a forbearance agreement with Apollo in March, which bought them a little more time to get their finances in order.

Apollo then sold a junior slice of the debt, totaling $25 million, to Joshua Crane and Robert Schwartz’s Spruce Capital Partners on June 28 — two days before the forbearance agreement expired — and the loan fell into default. At that point, Spruce launched a strict foreclosure process aiming to take over the project without going through an open auction.

AmBase separately sued Spruce to block the foreclosure, alleging that the company was in cahoots with Stern and Maloney. Bianco’s lawyers argued there was no other reason the developers would agree to a foreclosure that would wipe out their stake in the project. “The only logical conclusion from this otherwise irrational course of action is that [the] defendants have an undisclosed financial interest in the transaction with the lenders,” the complaint read.

The lawsuit also pointed to a glaring clause in the lender agreement that allows Spruce to tap Stern and Maloney as the project’s developers following foreclosure.

Terrence Oved, a partner at the New York law firm Oved & Oved, who is not involved in the case, said it’s “unusual for a borrower not to fight a foreclosure, especially from a junior lender.”

But a judge ruled in Spruce’s favor and on Aug. 30 the property went into foreclosure. Schwartz, who co-founded the investment and development firm in 2007, did not return requests for comment.

Intercreditor agreements “universally require that any lender in the debt stack can’t affiliate with the borrower,” said Meister. He argued that Spruce had “negotiated with Apollo to create an exemption that would allow [the firm] to affiliate with Stern and Maloney.”

Real estate attorney Joshua Stein, who is not involved in the case, said the ongoing dispute is an example of “tranche warfare,” when partners clash over different layers of a complex debt stack. “When shit hits the fan, these layers interact in ways you didn’t anticipate,” he said. Usually, he added, this kind of spat “will throw the whole thing out of whack, and the project will stop.”

Becker argued that Bianco could have easily prevented the foreclosure by approving the Baupost refinancing. “I was surprised that AmBase allowed the foreclosure to happen,” he said.

Anyone’s guess

AmBase’s appeal of the foreclosure is still pending, while the company’s suit against Stern and Maloney is also in limbo.

But the clock is ticking.

In the first half of 2017, Bianco’s firm paid $1.5 million for “professional and outside services” and recorded an operating loss of $2.4 million before taxes. As of June 30, AmBase held $358,000 in cash — down 39 percent from a year earlier.

In September, Bianco agreed to fund the company’s litigation with $7 million out of his own pocket. In return, AmBase will pay him back if the suit is successful, along with 30 to 45 percent of any damages awarded.

AmBase now looks a lot like it did two decades ago — a holding company with less than half a dozen employees and virtually no liquid assets, but legal claims that could yield more than $100 million. The question is: Can Bianco pull off another huge victory in court?

“I think it all hinges on whether he has the money for the suit,” said Thomas Niel, an independent investor who bought AmBase shares earlier in the summer, when its lawsuit looked more promising, but subsequently sold them. “Maybe I’ll buy some shares when the price goes down to like 10 cents,” he said. (The company’s shares were selling for 28 cents on Oct. 20, down from a 2017 high of $1.34 in early February.)

Bianco’s attorney Thompson said the appeal of the foreclosure could take more than a year, while the 2016 lawsuit is anyone’s guess. “Look, this is a multifront war,” he said.

This is the second of two stories about the latest troubles behind 111 West 57th Street.

Correction: an earlier headline incorrectly referred to 111 West 57th Street as NYC’s tallest condo project. It’s the second-tallest, behind Extell Development’s Central Park Tower.