The launch party for Extell Development’s 1010 Park Avenue in mid-October had all the trappings of a strong market: wall-to-wall brokers, a catered sushi bar and passed champagne flutes. But on a night meant to celebrate the luxe 11-unit condo project — where prices start at $12.95 million — Gary Barnett had a sobering message for brokers, telling them he’d cut prices three times ahead of the sales debut.

That one of the city’s most active developers chose such a forum to address soft market conditions illustrates just how serious the proliferation of price cuts and concessions has become as developers look to unload sponsor units.

“Everything is being sold at huge discounts, which is how the market is moving,” said Donna Olshan, founder of Olshan Realty, which tracks the number of contracts signed for Manhattan properties above $4 million.

The data paints an ugly picture of the Manhattan new development sector, which has been steadily declining for the past 18 months.

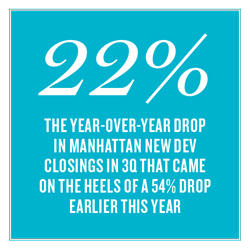

The low point came in the first quarter of 2018, when new development sales logged a 54 percent year-over-year decline, with only 259 closed transactions in total for the quarter, according to data from Miller Samuel. During the third quarter, meanwhile, sales were down 22 percent year-over-year, with 360 new development closings.

Given that there were nearly 1,000 new development units on the market in Manhattan during the third quarter — not to mention thousands of additional shadow inventory units that developers strategically keep off the market — that transaction rate is weak at best.

Given that there were nearly 1,000 new development units on the market in Manhattan during the third quarter — not to mention thousands of additional shadow inventory units that developers strategically keep off the market — that transaction rate is weak at best.

The reality is one that developers and brokers have been dealing with for nearly two years, as The Real Deal has been extensively chronicling.

Appraiser Jonathan Miller said that the slide in new development closed sales still reflects the fact that legacy contracts — those signed in 2015 and 2016 — are drying up. Though it’s hard to know precisely how many are left, they’re being burned through quickly now that buyers can purchase completed units (versus buying off of floorplans).

However, condos that failed to sell over the past 18 months are stuck with designs and prices conceived of during the booming market of two to three years ago. As of Oct. 19, there were 364 contracts signed on condos priced at $4 million and up, according to Olshan. Although that number has ticked up in recent years, it’s significantly less than the 409 contracts signed during the same period in 2014.

“That early in the cycle, developers were going after bigger product,” Miller said. “But they’re coming into the market that’s already re-set away from superluxury.”

Buyers today — who’ve gotten used to the softer market — also don’t want to pay full price. “Everybody today comes in and expects a discount,” HFZ Capital Group’s Ziel Feldman told the Wall Street Journal last month.

At 1010 Park, Barnett lowered the projected sellout by about 10 percent since originally conceiving of the tower, located next to Park Avenue Christian Church. It now stands at $222 million, after Barnett shaved off $25.75 million in September, according to the state Attorney General’s office.

Likewise, the developers of 125 Greenwich have recently trimmed several million dollars off the total sellout price of $868.4 million, and Magnum Real Estate has discounted units at 100 Barclay — a project that is 70 percent sold after hitting the market in late 2015. In mid-October, SCG America relaunched Manhattan View at MiMA with lower prices.

“The residences are all built and finished, which is a great asset in this marketplace,” said Tricia Cole, an executive managing director at Corcoran Sunshine Marketing Group, which is handling sales.

According to StreetEasy, the share of new developments citywide that are being sold with price discounts is 10.2 percent, compared to 5.6 percent in 2016. While that may not sound all that dramatic, it’s the highest level since 2012, and pockets of the city have even bigger discounts. In Upper Manhattan, for example, StreetEasy data shows 18.4 percent of new developments sold at a discount this year, compared to 5.9 percent in 2016.

Not every price cut is drastic, though.

“Sometimes, it’s just a small adjustment that does the trick,” said Steven Rutter, director of Stribling Marketing Associates. That, he said, was the case at the Shephard, a 38-unit condo at 275 West 10th Street, which was developed by the Naftali Group and went on sale in 2016. This fall, SMA staged and discounted six apartments, three of which have since been snapped up. They include a three-bedroom originally asking $8.75 million; the price was cut to $8.25 million in September and went into contract three weeks later.

Added urgency

For developers and the brokers marketing their projects, this sluggish market is not expected to improve anytime soon.

In fact, the urgency to unload units now is intensifying because there’s a massive batch of inventory lingering on the market.

Although only 2,000 new condos are expected to hit the Manhattan market in 2019, Miller projected that there will be 7,900 unsold units sitting on the market this year and more than 8,600 next year.

Vickey Barron — who recently joined Compass from the Corcoran Group — said discounts have picked up as developers who need to satisfy their lenders by hitting sales benchmarks get realistic.

From left: 91 Leonard, 49 Chambers Street and 100 Barclay

But price chopping can eat into developers’ profits; as an alternative, some developers struggling to sell out their condos have sought inventory loans on unsold units.

In June, Ian Bruce Eichner landed a $167.5 million inventory loan at 45 East 22nd Street. And in September, CBSK Ironstate landed a $102.8 million inventory loan at the Lindley in Murray Hill.

“Some of them were stubborn [earlier in the cycle] in not giving concessions or discounts,” Barron said. “Eventually, it snowballs. You have to play the same game.”

And in addition to discounts for buyers, that game includes incentives for brokers who close deals at their buildings. TRD was writing about those incentives as far back as early 2017, but they have yet to subside and actually picked up again a few months ago.

At the 99-unit 49 Chambers Street, the Chetrit Group is offering buyers’ agents 50 percent of their commission at the contract signing — rather than making them wait for their full pay at the closing.

Meanwhile, Toll Brothers — which has been one of the most aggressive developers on this front since the market started softening — is offering agents a $25,000 bonus if they deliver a signed contract at 91 Leonard. The developer is currently selling eight buildings citywide, including 55 West 17th Street and the Sutton at 959 First Avenue and is known for offering an array of incentives.

There’s no data to show that incentives work, but for some developers, it’s a matter of getting buyers in the door — or back to the negotiating table.

“They pull stuff out of a hat,” Barron said, “and curate something that’s appealing to a buyer.”

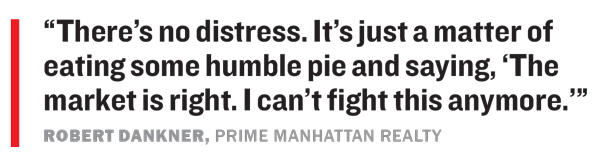

Prime Manhattan Realty’s Robert Dankner, who mostly works with buyers, said that in mid-October, he got three contracts signed after developers — who initially rejected his clients’ below-ask offers — reconsidered.

One was for a condo asking just under $15 million, which had been on the market for 200-plus days, he said. His client signed a contract in the mid-$12 million range. “The asking price seemed a bit lofty to begin with,” Dankner said.

One was for a condo asking just under $15 million, which had been on the market for 200-plus days, he said. His client signed a contract in the mid-$12 million range. “The asking price seemed a bit lofty to begin with,” Dankner said.

Still, he said, “nobody is giving away anything for free.”

“There’s no distress,” he said. “It’s just a matter of eating some humble pie and saying, ‘The market is right. I can’t fight this anymore.’”

The broker shuffle

Not surprisingly, developers and brokers have been at odds at some buildings, so hirings, firings and resignations have been on the rise lately, all standard fare in a slower market.

Last month, for example, Corcoran Sunshine replaced Nest Seekers International’s Ryan Serhant at Manhattan View at MiMA, while Bold New York landed JDS Development Group’s American Copper Buildings after Citi Habitats resigned.

Meanwhile, Douglas Elliman is now marketing JDS’s 111 West 57th Street after the developer terminated Corcoran Sunshine (prompting a $30 million lawsuit from Corcoran, which alleged the developers’ infighting and financial woes sabotaged the sales effort). And, earlier this fall, Shlomi Reuveni’s eponymous firm took over the 123-unit Charlie West in Hell’s Kitchen from Elliman.

Sources say that in many cases developers are under intense pressure to show the market — and their lenders — that they’re doing something. “One of the boxes that they can check is, ‘Change broker,’” said Kelly Kennedy Mack, president of Corcoran Sunshine.

She said the biggest challenge in today’s market is managing expectations. Although she said the market is healthier than people think, it has weathered tax reform, political uncertainty and stock-market fluctuations.

“There’s a lot more supply out there and buyers are really uncertain, and frankly, they’re confused,” she said.

She also added, however, that final sales prices today are consistent with where they were in 2011 and 2015 — and that developers, buyers and sellers were all content back then. “It’s just interesting how your expectations can change so much so quickly with a couple of, you know, really strong boom years,” she said.

Some brokers, however, see the shifting new development market and the shuffling of sales teams as an opportunity.

“I want to be second in everyone’s building; it’s tough to be first when you’re working off development plans that were penciled in 2014 and 2015 when the market was on fire,” said Jordan Sachs of Bold New York. The market, he noted, has since shifted 10 to 15 percent. “You’re never going to last as first position.”

Bright spots

There are some bright spots in the market. Several pockets of the city, including Brooklyn and the Upper West Side, are seeing demand outpace supply.

“The Upper West Side had the least available inventory for years, so it needed new development,” said Stephen Kliegerman, president of Terra Development Marketing, which includes Halstead Property Development Marketing and Brown Harris Stevens.

“What’s really dragging down the market are the same damn projects that have been dragging down the market for the past 18 months,” he said.

While Kliegerman declined to name those projects, buildings that have been on the market since that time include Alexico Group and Hines’ 56 Leonard, RFR’s 100 East 53rd Street and even Extell’s One57, which has a few sponsor units left.

Likewise, new development prices in Brooklyn have remained more competitive than Manhattan. The median sale price in Brooklyn new development dropped only 1 percent during the third quarter, to $905,783, according to Miller Samuel. In Manhattan, the median price was $2.55 million — down 8 percent.

Kliegerman — whose firms are marketing the Brooklyn Grove, 21 Powers and 264 Webster in Brooklyn, among others — said that’s a function of the kinds of buyers Brooklyn attracts.

“In Brooklyn, a lot of our buyers need housing,” he said.

As a result, projects are better suited to meet buyers’ needs, compared to Manhattan, where aspirational housing was built for a national and international marketplace looking for investment properties.

The optics of new development tend to be all or nothing — somewhat unfairly, Miller said. “In down markets, the expectation is that nothing sells. That’s not true,” he said. “It’s just that the intensity isn’t there.”