Two years ago, Douglas Elliman won the Holy Grail of property management assignments: Co-op City. With 35 buildings and 15,000 units in the Bronx, the Mitchell-Lama project is the country’s largest cooperative housing complex.

Co-op City’s board hired Elliman in May 2016, more than a year after abruptly firing Marion Scott Real Estate over allegations that the company mishandled its duties. Marion Scott has disputed the claim. The co-op board, Riverbay Corporation, self-managed the complex for more than a year but ultimately hired Elliman after an 18-month search for a replacement.

“If you are in the business, there are a couple places that you want,” said James O’Connor, president of Douglas Elliman Property Management. “And I’m a Bronx guy. So it makes sense for us.”

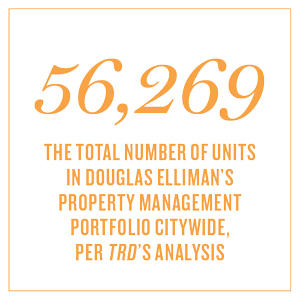

It was that new gig — along with several new upscale condominium developments — that propelled Elliman to the top of The Real Deal’s latest rankings of the city’s biggest property management firms, which tallied companies by the number of residential units they oversee in Manhattan and the outer boroughs.

The analysis, based on data from the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, showed that companies with a national presence and the resources to handle massive portfolios continued to dominate the third-party property management game.

“We’re not a cyclical business, but we do depend on volume,” said Michael Rothschild, vice president of Midtown-based AJ Clarke Real Estate, which acquired the smaller Manhattan-based firm Fenwick Keats last year.

“We’re not a cyclical business, but we do depend on volume,” said Michael Rothschild, vice president of Midtown-based AJ Clarke Real Estate, which acquired the smaller Manhattan-based firm Fenwick Keats last year.

Property management as an industry is relatively insulated from the city’s volatile real estate market; it’s rarely impacted by falling sales prices or the seemingly fickle appetites of foreign investors. But the business — which generated $81 billion in revenue nationwide in 2017, per business research firm IBISWorld — is highly competitive. And it’s becoming increasingly difficult for smaller, boutique firms to survive, especially as landlords and condo and co-op boards look for ways to cut costs.

At the same time, the job is becoming more complicated as the city continues to issue regulations that largely fall to property managers to carry out, sources in the business say.

“We’re expected to be geniuses,” said Ellen Kornfeld, vice president and partner at the Lovett Group, which has offices in Midtown and College Point in Queens. “We’re expected to know everything, but no one wants to pay for the service.”

Top of the heap

In Manhattan, many of the leading management firms are nationally known brands with multiple offices outside of New York.

Douglas Elliman Property Management, which took the top spot with 28,022 units, is part of the residential brokerage giant with 113 offices across the country. In Manhattan, Elliman scored several new high-end condo developments, including 150 Charles Street, 215 Chrystie Street and 111 Murray Street. Its parent company, Howard Lorber’s Vector Group, is an investor in the Murray Street tower, which is being developed by the Fisher Brothers and Witkoff Group.

“We get some but not all of the buildings that [our] parent company invests in, because a lot of the time they are not the majority investor,” O’Connor said. “We get what we can.”

FirstService Residential — which is based in Florida and runs its New York office out of Midtown — came in second in Manhattan with 27,680 units. The firm, which specializes in luxury condo and co-op buildings, ranked first last year.

Dan Wurtzel, president of FirstService’s New York operations, said the rental buildings the company manages — like JDS Development’s American Copper Buildings — require hotel-level amenities and services.

“The type of buildings that are now in the rental market are significantly different than what you saw 10 or 20 years ago,” he said. “The type of management that you need isn’t the old-school rental management.”

In the past decade, FirstService has acquired a few other businesses, including Manhattan-based Goodstein Management and Brooklyn-based Live Right Management.

The top 20 property management firms in Manhattan

| RANK | FIRM | 2018nRESIDENTIALnUNITS | 2017nRESIDENTIALnUNITS | PERCENTnCHANGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DouglasnEllimannPropertynManagement | 28,022 | 27,465 | 2.03% |

| 2 | FirstServicenResidential | 27,680 | 27,877 | -0.71% |

| 3 | AKAM LivingnServices | 26,799 | 24,267 | 10.43% |

| 4 | HalsteadnManagement | 16,267 | 19,313 | -15.77% |

| 5 | Charles H.nGreenthal &nCo. | 13,684 | 13,008 | 5.20% |

| 6 | Orsid Realty | 13,148 | 12,504 | 5.15% |

| 7 | RosenAssociates | 11,974 | 13,146 | -8.92% |

| 8 | Brown HarrisnStevens | 10,856 | 9,465 | 14.70% |

| 9 | MidboronManagement | 10,197 | 9,583 | 6.41% |

| 10 | Maxwell-Kates | 10,130 | 11,163 | -9.25% |

| 11 | Tudor RealtynServices | 7,082 | 7,590 | -6.69% |

| 12 | RoseTerranManagement | 6,593 | n/a | n/a n/a |

| 13 | PrestigenManagement | 6,347 | 6,696 | -5.21% |

| 14 | CenturynManagement | 5,570 | 6,005 | -7.24% |

| 15 | AJ ClarkenReal Estate | 5,236 | 5,505 | -4.89% |

| 16 | AndrewsnOrganization | 5,115 | 5,121 | -0.12% |

| 17 | MetronManagementnDevelopment | 5,111 | 3,919 | 30.42% |

| 18 | Gumley Haft | 4,047 | 4,594 | -11.91% |

| 19 | MatthewnAdamsnProperties | 3,709 | 3,897 | -4.82% |

| 20 | C+CnApartmentnManagement | 3,678 | n/a | n/a |

Midtown-based AKAM Living Services, which also has operations in Florida, ranked third with 26,799 units, while Halstead Management, a subsidiary of the national corporation Terra Holdings, came in fourth with 16,267 units. AKAM President Michael Berenson noted that the parent companies of the firms that ranked first and second this year are both publicly traded and that both Douglas Elliman and First Service are comprised of several other companies.

“I think it’s noteworthy that we built our company with no mergers or acquisitions,” Berenson said.

Charles H. Greenthal & Company, a family-owned firm located on Park Avenue and 34th Street, rounded out the top five with 13,684 units. Representatives for the company declined to comment.

In the outer boroughs, many of the same companies dominate, but a larger number of top property management firms specialize in affordable housing. That market is notably bigger in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens.

Elliman also ranked first in the outer boroughs with 28,247 units. FirstService came in second with 25,622 units, followed by two Queens-based companies that focus on affordable housing management: Metro Management Development with 20,556 units and Wavecrest Management with 15,514 units. AKAM took the fifth spot in the boroughs with 11,023 units. Representatives for Metro Management declined to comment.

“For us, in the affordable world, it’s a real boost and can be a life-changing experience,” said Susan Camerata, Wavecrest’s chief financial officer. “There’s such a need for housing in the city, and an even greater need for lower- and middle- income housing.”

Shedding resi units

For the most part, this year’s ranking closely follows 2017’s, with a little shuffling among the top management firms.

But more than half of the top 20 companies in Manhattan lost apartments in the past year. Halstead logged the biggest loss at 15.8 percent, or 3,046 units. Gumley Haft saw the second biggest loss with a 11.9 percent year-over-year decrease, or 547 units.

Some of the leading firms in the outer boroughs also saw losses. FirstService saw the biggest drop with a 7.83 percent year-over-year decline, or 2,178 units. AKAM saw the second largest loss with 5 percent dip, or 584 units.

Some of the leading firms in the outer boroughs also saw losses. FirstService saw the biggest drop with a 7.83 percent year-over-year decline, or 2,178 units. AKAM saw the second largest loss with 5 percent dip, or 584 units.

Metro Management, meanwhile, saw the largest uptick in units in Manhattan with a 30.42 increase (1,192 units), and Elliman had the largest increase of the outer borough firms due to Co-op City.

Elliman still hasn’t properly registered with HPD as the complex’s managing agent, as required by law, which is why the project didn’t show up on TRD’s ranking last year. Neither the company nor HPD could provide a reason for the lack of registration.

The causes of fluctuations in a firm’s unit count can vary: A change in ownership or a change in condo or co-op board could lead to the property manager being terminated or resigning from a building. And, sometimes, boards simply opt for a cheaper manager.

“There are certainly companies that charge extremely low prices,” said Michael Wolfe, president of Chelsea-based Midboro Management, ranked ninth on TRD’s Manhattan ranking with 10,197 units. “They get a lot of business and lose a lot of business,” he added. “We’re more about continuity.”

Wolfe declined to name companies that skimp but said the city’s leading management firms tend to be more selective with clients. “Not everyone is looking to take on every single building that calls,” he said.

The industry has also undergone a fair amount of consolidation in New York in recent years. Rose Associates sold its condo and co-op business to Terra Holdings last year, for example. Terra’s new subsidiary, RoseTerra Management, ranked 12th in Manhattan with 6,593 units.

And in August 2017, AJ Clarke acquired Fenwick Keats, taking over roughly 40 buildings from the boutique firm. The company ultimately ended its contract with a few of the buildings it inherited from Fenwick, while some of the landlords at those properties opted to hire different management firms.

“In our business, economies of scale are so important,” said AJ Clarke’s Rothschild, who added that being acquired is often in a smaller firm’s best interest. “In general, it’s very difficult to run a small property management business in New York City.”

Co-op City’s board hired Douglas Elliman to manage the massive Bronx housing complex in May 2016.

In order to thrive in such a competitive market, property management firms need to have the resources to juggle high volumes of buildings, sources say.

Mitchell Barry, president of Chelsea-based Century Management, which ranked 14th in Manhattan with 5,570 units, said that while many boutique firms have found their niche in the city, they still face pressure to reduce rates for their services.

Costs for management services vary depending on location and building type. Generally speaking, property managers charge a flat annual fee, including maintenance costs, of $500 to $1,000 per unit for condos and co-ops, according to those in the business. The standard monthly rates that managers charge at rental properties, meanwhile, have traditionally ranged from 3 to 5 percent of a building’s rent roll. But as rents rise, the percentages get pushed down, sources say.

“It’s a continuous problem in our industry that they are trying to chisel our fees down,” Barry said. “It becomes a balancing act. How many buildings can you give a manager before they break?”

Shifting business

The nature of property management has transformed over the last few years.

Much of the job is still coordinating building repairs, collecting rent, paying vendors and assuring compliance with city and state regulations. But there’s been a push to provide hotel-level concierge services in buildings, not just in luxury condos but in rentals as well.

“Lately, there’s been a bit of an arms race with amenities. Renters are displaying increased expectations.” said Phil LaVoie, COO of the privately held development firm Gotham Organization, which manages its own properties, mostly located in Manhattan. LaVoie said his company decided to switch to managing its own buildings in 2016 to have greater control over its portfolio and brand.

These days, a growing number of tenants expect their building’s manager to be available 24/7, said FirstService’s Wurtzel. “We recognize that the standard work hours don’t really exist anymore,” he said. “When [tenants] want to be able to contact management, it’s really up to management to be accessible.”

These days, a growing number of tenants expect their building’s manager to be available 24/7, said FirstService’s Wurtzel. “We recognize that the standard work hours don’t really exist anymore,” he said. “When [tenants] want to be able to contact management, it’s really up to management to be accessible.”

At the same time, escalating payroll and real estate taxes are leading to increases in maintenance costs in co-ops, said Kornfeld of the Lovett Group, which ranked sixth in the outer boroughs with 10,217 units. The average maintenance and common charges for a Manhattan co-op weigh in at around $1,500 per month, according to appraisal firm Miller Samuel.

As property taxes and building fees go up, long-time condo and co-op owners are pushed out and replaced by buyers with different priorities and higher expectations, Kornfeld said.

In turn, property managers increasingly play the role of impartial mediator.

“The older population prefers the status quo — if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” Kornfeld said. “The new people want to see gyms, new hallways, a new lobby, roof decks, you name it.”

In the affordable housing realm, advances in technology have created opportunities for property managers to help improve their tenants’ quality of living outside their buildings.

Wavecrest’s Camerata said her company has participated in a pilot program with the city comptroller’s office in which it submits information to credit card companies showing that tenants consistently paid rent on time. The program aims to help tenants improve their credit scores.

The top 10 property management firms in the outer boroughs

RANK FIRM 2018nRESIDENTIALnUNITS 2017nRESIDENTIALnUNITS PERCENTnCHANGE 1 DouglasnEllimannPropertynManagement 28,247 13,468 109.73% 2 FirstServicenResidential 25,622 27,800 -7.83% 3 MetronManagementnDevelopment 20,556 20,397 0.78% 4 WavecrestnManagement 15,514 15,429 0.55% 5 AKAM LivingnServices 11,023 11,607 -5.03% 6 Lovett Group 10,217 9,845 3.78% 7 PrestigenManagement 6,791 6,066 11.95% 8 Reliant RealtynServices 6,748 6,499 3.83% 9 C+C ApartmentnManagement 6,627 6,703 -1.13% 10 LangsamnPropertynManagement 6,387 n/a n/a

And while communicating with tenants — as well as filing work orders and making rent payments — has largely been automated, there’s still that expectation of getting a personal response, said Dan Wollman, CEO of Gumley Haft, which ranked 18th in Manhattan with 4,047 units.

“You still need people running buildings,” he said, noting that if tenants have a problem, “they send an email or fill out a work order, but they [still] want to talk to you.”

Managing disasters

Every year, property managers must comply with a series of new regulations, and industry veterans say they’ve seen an escalation in recent years.

A state law that went into effect this year, for instance, requires condo and co-op boards to annually disclose potential conflicts of interest to other owners in the building. That includes ties to a specific company, like an electrician the board is considering hiring, for instance. And it’s up to the management firms to make sure the board complies, industry sources say.

“Over the last 33 years, it’s gone from winter guard notices and façade inspections to dozens and dozens of laws and regulations,” Wurtzel said. “It’s made the property management industry way more complex than it used to be.”

Meanwhile, new regulations tend to follow disasters.

Local Law 152, which goes into effect in January, requires gas piping systems in buildings to be inspected at least once every five years, for example. That measure followed the gas explosion in the East Village in March 2015 that killed two people and injured several others. Authorities believe the explosion was caused by an attempt to illegally siphon gas from a restaurant on Second Avenue.

And by 2020, all elevators in the city must be equipped with door-lock monitors, which prevent elevators from moving if the doors are open. Those upgrades, while important for safety reasons, will be particularly pricey — upwards of $15,000 per elevator — for older lifts that don’t have the software already built in. The legislation requiring the devices followed the 2011 death of a 41-year-old woman at 285 Madison Avenue, then owned by the ad agency Y&R.

“Compliance has a pendulum effect,” said Orsid Realty’s president, Neil Davidowitz. “Things that transpire in the city cause more stringent legislation.”

Though not particular to property managers, the city and state’s new sexual harassment laws also apply to the industry. Starting next year, all employees, including building personnel, must undergo annual sexual harassment training.

Gumley Haft’s Wollman noted that the New York City Department of Buildings has been particularly strict in its application of Local Law 11, which requires owners of buildings higher than six stories to have their exterior walls inspected every five years.

He said the DOB’s been less willing to approve reports by engineers and architects who conduct the inspections. In the past, he said, the agency would sign off on the reports unless there was something particularly “egregious.”

“I think there’s pressure on the DOB to make sure the conditions in New York are safe, which I think is a good thing,” Wollman said. “I think sometimes they go a little overboard.”

Joseph Soldevere, a spokesperson for the DOB, said the City Council has passed several bills since 1980 that have ramped up protections for pedestrians from potentially dangerous building façades.

“DOB enforces those laws, as we are required to do,” Soldevere said in a statement. “These laws, along with DOB’s enforcement efforts, are critical to keeping New York’s sidewalks safe for residents, workers and visitors.”

The regulations also make the industry less appealing to younger generations, Kornfeld said.

“If you are going to be an investment banker, it’s sexy and it pays a lot,” she said. “Why would you go into property management?”