here.) Meanwhile, Carlton opened a new office in Athens last month and a London outpost in April, adding to its locations in Chicago, Los Angeles and Florida.

here.) Meanwhile, Carlton opened a new office in Athens last month and a London outpost in April, adding to its locations in Chicago, Los Angeles and Florida.

The way Michaels tells it, Carlton’s current level of activity is due to a unique confluence of market factors that play to his strengths.

Michaels is fond of repeating that Carlton specializes in raising “passive, promotable equity” for clients — tapping high-net-worth individuals and institutions to access 80 to 100 percent of the capital required for a real estate project. Now, in a difficult deal-making environment, with many of the pre-recession players out of commission, Carlton is uniquely positioned to clean up.

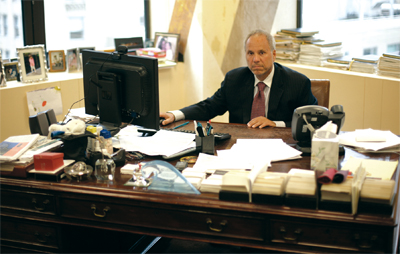

“The real estate market right now is obviously very volatile,” Michaels said, excitedly pacing across his glass-walled corner office at 560 Lexington Avenue. “But I love it. I couldn’t be having more fun.”

Carlton’s detractors have a different take, saying Michaels’ accomplishments are exaggerated by his courting of the press and frequent e-mail blasts, to a database of several hundred thousand contacts in the United States and abroad, when the firm is working on a deal.

And Carlton’s reputation is indelibly marked by Michaels’ notorious temper, which has earned him comparisons to Ari Gold, the verbally abusive talent agent played by Jeremy Piven on HBO’s “Entourage.” Michaels’ friends and foes alike note that he is one of the industry’s toughest bosses, and that the firm cycles through employees at a rapid clip.

Carlton has “the highest turnover in the history of real estate companies,” said one industry source. “He has a list of hundreds of people he’s hired [who] have quit.”

Michaels is also famous for his grueling schedule. One former employee bemoaned Michaels’ mandatory Sunday-morning conference calls — which take place on holidays and long weekends, too. If staffers miss them, “there’s hell to pay,” one former employee recalled. “He just has no regard for someone’s personal life or schedule.”

Michaels vehemently denied that Carlton has the highest turnover in the business, adding that the firm has had “many” employees stay with the firm for at least 10 years. A self-described “workaholic,” he laughed off the comparison to Piven’s character. But he doesn’t deny that he’s a tough boss.

“Carlton is not for the fainthearted,” he said. “If you’re not serious about work, this is probably not a good place. But if it’s someone who’s motivated and wants to do well, this is a great place to work.”

Other people’s money

Howard Lee Michaels was born in Flatbush, Brooklyn, in 1955. He was, he told The Real Deal in 2008, “a fat Jewish kid in an all-Italian neighborhood.”

Now fit, if stocky, Michaels has an intense gaze that frequently strays towards his ever-present BlackBerry. His father worked in a retail carpet store, he explained, and as a kid, Michaels helped out on weekends and over the summer. He swept floors at first, eventually working his way up to sales.

Michaels quickly figured out that he liked making money, and he had a knack for it.

“Some guys are good at playing football,” he said. “I was good at business.”

In 1977, he graduated from American University in Washington, D.C., and began the circuitous career path that would eventually lead him to real estate.

He landed the sales job at 3M within three weeks of graduating from college. From there, he moved to Connecticut General Life Insurance, where a cold call led to a job at the Manhattan-based real estate syndicator Island Planning.

Michaels did well at Island. The complex financial instruments of today hadn’t yet emerged, and syndicators — who pooled together funds from multiple investors — dominated the market.

“By the time I was 30,” he recalled, “I had a chauffeur-driven limousine, I had a day driver, I had a night driver, I had a house in the Hamptons.”

Perhaps more important, he’d discovered the skill set he would cultivate for the rest of his career: scrounging up capital for real estate deals.

“I was always good at raising money for projects,” Michaels said.

In the depressed real estate market of the early ’90s, Michaels became a partner at a Long Island-based company called Carlton Brokerage. Along with the other owners, he created a new company called Carlton Property Auctions.

“It was a difficult time to sell anything,” recalled Peter Hauspurg, chairman and CEO of Eastern Consolidated, who organized an auction of distressed commercial assets with Michaels in 1993. The two recruited sellers to take part in the auction, compiling “a thick book of distressed properties,” Hauspurg remembered. “We ended up with hundreds of assets.”

Some 1,000 people showed up to the event, held at the Starlight Room on the top floor of the Waldorf-Astoria. “It worked — we sold a lot of property,” Hauspurg said.

Michaels continued expanding Carlton’s auction business. In the mid-’90s, he parted ways with his partners, formed the Carlton Group (they retained Carlton Brokerage) and moved it into Manhattan. By that time, the industry was changing, as securitization replaced syndication. In 1994, J.P. Morgan was widely credited with creating the first credit default swap — a financial instrument that serves as a type of insurance policy against default–and changing the face of modern finance.

Carlton, along with its clients, began delving into these more complicated transactions.

“That was a great segue for us, because a lot of our auction clients were the investment banks,” Michaels explained. “When those banks changed their focus, we took those relationships and started doing financing.”

Then, in 1998, an old client from Michaels’ syndication days asked him for help raising the subordinate capital for the purchase of an office building in Washington, D.C. “Within 48 hours, we got four offers for them,” he remembered.

The deal wound up fizzling, but Michaels had figured out a way to set himself apart from his competitors.

“What does everybody in real estate want? OPM — other people’s money,” Michaels said. “So I decided I was going to become the best person at arranging deals with other people’s capital.”

That strategy, he said, has allowed Carlton to do some of the industry’s highest-profile deals.

For example, Michaels said: “In 2006, when Harry Macklowe wanted to pay off Vornado and [George] Soros, who had some very expensive mezzanine on the General Motors Building, I brought in Jamestown, who gave him a $300 million check to pay them off and build out the Apple Store. And when Charlie Kushner needed $335 million to pay off his mezzanine debt on 666 Fifth Avenue, I brought in a dozen lenders who gave him $525 million.”

More recently, at 737 Park Avenue, Michaels “got the buyer to recognize what the market would give him,” said one Carlton client who asked not to be named. “He found the equity, which was a miracle, if you ask me. He got quality debt for a condo conversion, and the market was disintegrating at the time, too. That was a hard, hard deal. I don’t believe anybody else could have gotten that deal done.”

This, and Carlton has only around 50 employees, making it relatively diminutive compared to competitors like Eastdil Secured, CB Richard Ellis and Cushman & Wakefield.

Competitors note, however, that the largest firms have only a few brokers who specialize in Carlton’s niche. “Even if he only had 12 guys, he’d be larger than all of them,” said one. “Howard could well be one of the biggest players around in that sector.”

Whatever the size, today’s economic climate is particularly beneficial to Carlton and similar companies, Michaels said.

Before the recession, “it was a different market to compete in, because you had all the super real estate banks controlling the market,” he said. “You had Lehman, you had Wachovia, you had Bear Stearns, you had Credit Suisse, you had Goldman.”

Buyers and owners who had relationships with these players could “get all of their capital needs met,” he said.

That’s no longer the case, and borrowers need more help from brokers. “Clearly, in an uncertain environment, the perceived value of an intermediary is more significant,” said Simon Ziff, president of real estate capital advisory firm Ackman-Ziff.

That gives Carlton, and firms of its ilk, a wider opening to swoop in.

“We’re getting a payoff for the last 25 years of traveling the world, and going to every conference, and having relationships with investors throughout the world who now have money to invest in U.S.-based deals,” Michaels said.

Marine-style business

Carlton has no shortage of satisfied customers.

Murray Hill Properties’ Norman Sturner openly credits Michaels for saving the day at 1180 Sixth Avenue and at One Park Avenue, where Carlton arranged the financing for Vornado’s $180 million recapitalization of the 925,000-square-foot office building, which had been on the brink of foreclosure.

Both properties were “in financial crisis,” before he hired Carlton, Sturner said.

Michael Ashner, the chairman and CEO of Winthrop Realty Trust, hired Michaels to manage the firm’s attempted foreclosure at Stuyvesant Town in 2010 with the other senior mezzanine lender at the project, Pershing Square Capital Management. (The deal didn’t go through, but Ashner said that had “nothing to do with” Michaels. The parties ended up making a deal with CW Capital instead.)

“It was a very complicated foreclosure, and [Carlton] did an excellent job,” Ashner said.

“Whenever we’re involved in these mezzanine foreclosures, we use him and his firm.”

One element of Michaels’ success is his industry connections.

“His Rolodex is as good as anybody’s,” Sturner said. “His tentacles go out to everybody.”

But Michaels and others say his success is chiefly a function of persistence. One broker described Carlton’s technique as “calling 100 lenders, and finding someone interested in the deal.”

Michaels “doesn’t stop on Friday afternoon and resume on Monday,” Ashner explained. “If a thought occurs to him, he pursues it on Saturday evening, and he’ll call you. International time zones don’t affect him.”

While Sturner and Michaels were working on 1180 Sixth and One Park, “he and I spoke literally five times a day, seven days a week,” Sturner said, “and when we couldn’t speak, we would text.”

On some occasions, Michaels said, he has even put up deposit money from his own funds to facilitate a client transaction.

He does take time off, he said, to be with his five children and his second wife, Jennifer Bayer Michaels. But it’s clear that work is never far from his mind. On a family trip to a Murano glass factory in Venice this summer, for example, Michaels ordered an 18-carat gold sculpture of a bull for the Carlton office.

One reason Michaels works so hard is out of necessity. With his blue-collar background and lack of a brand-name firm, he faces a certain snobbery within the industry.

Many of the country’s high-profile real estate assets are owned by institutions, like investment banks or insurance companies. When it comes to selling their property, they often turn to big-name, white-shoe brokerage firms, like Eastdil (see related story here).

“Institutions tend to go to institutions,” Ashner explained.

Another real estate executive put it more bluntly: “I’ve got a whole team of associates with MBAs from Harvard, Columbia and NYU. We need that, because that’s the peer-to-peer set you need if you’re representing Carlyle and Blackstone and Rockpoint.”

As a result of this dynamic, Michaels explained, Carlton has carved out a niche working with individual investors, like Macklowe, rather than with institutions, and more often with borrowers, who typically have more complicated financing needs than sellers.

“I do think that, for an institution, it’s sometimes easier for somebody sitting on a committee to pick one of the name-brand companies because it’s a safer choice,” Michaels said.

That means Carlton’s deals tend to be more difficult transactions.

“If it’s a vanilla deal, Howard will have a hard time getting that deal,” said one executive. “These are the tough deals he does — people don’t give him the easy deals.”

Some might view this as a shortcoming, but with his oft-cited gift for public relations, Michaels paints it as a selling point.

“Anybody can raise money for a fully occupied building with lots of cash flow,” Michaels said. “That’s not what we do. We’re like the Marines — we do the tough deals, we do the big deals, we do the time-sensitive deals.”

Bark worse than bite

Michaels’ Marine-like mentality may be the key to Carlton’s success, but it’s incredibly difficult on his staff, some say.

“He works people to death,” said one industry observer, voicing an opinion shared by the many former Carlton employees now spread throughout the industry.

There are the long hours and Sunday morning phone calls — of which Michaels says, “we start on Sunday — what can I tell you?”

Worse, former employees say, is his outsized temper, which is notable even for the cutthroat real estate industry.

Clients and fellow brokers say Michaels is often charming and funny — with a few rough edges — in his dealings with them. But with his staff, it’s a different story.

“Many times at staff meetings, he yells at people, insults them,” said one former employee, who said he witnessed Michaels call one staffer “a fat, out-of-shape loser.”

Michaels said he doesn’t recall that specific comment, but doesn’t deny that he’s “very intense and very passionate. I’m not above raising my voice if something needs to be emphasized.”

He added: “If people don’t do their homework and don’t come to work prepared, they probably shouldn’t be working at Carlton.” His clients are incredibly demanding, he said, and “not everybody is willing to put in the effort that’s required, so we can’t keep people forever if they don’t produce.”

Those who know him well say his bark is worse than his bite, and that his aggressive demeanor conceals a caring persona.

Still, the extra time it takes to hire and train new people can’t be good for the bottom line, observers noted, and the firm’s revolving-door reputation makes some clients reluctant to work with Michaels.

Some of Michaels’s detractors went so far as to suggest that Carlton isn’t as successful as it appears. Through Carlton’s well-oiled P.R. machine, they say, Michaels sometimes downplays or takes credit for other firms’ work.

Michaels strongly denies those claims.

He added: “Carlton is one of the most successful real estate advisory firms. Whatever we’re doing works.”