Tropical Storm Irene left New York City mostly unscathed, but the city hasn’t always been so lucky. Manhattan has weathered its fair share of natural and man-made disasters, often with long-lasting effects for the real estate market. This month, The Real Deal looked back at the worst disasters in the city’s history, real estate-wise.

British occupation

British OccupationDuring the Revolutionary War, some 30,000 British and mercenary troops occupied the city, severely damaging its infrastructure, according to New York City historian and real estate attorney Warren Shaw. Gunfire destroyed more than 40 percent of the city’s buildings, including the original Trinity Church, he said, while the nonmilitary population fell from 25,000 to around 3,000. According to Shaw, who is senior counsel in the commercial and real estate litigation division of the office of Corporation Counsel of the City of New York, “No other American city experienced a comparable level of devastation during the Revolutionary War.” Luckily, the city’s brief status as capital of the new United States prompted a bevy of construction after the war, including the rebuilding of Trinity Church and new docks along the East and Hudson rivers.

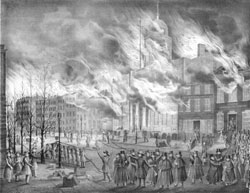

The Great Fire of 1835

The Great FireThe Great Fire is said to have caused more property damage, proportionally, than any other event in New York City history. The blaze began in snow-covered Lower Manhattan on the bitterly cold evening of Dec. 16. With the East River frozen solid, firefighters had to cut holes in the ice to get water. The fire flattened everything in its path, consuming more than 20 blocks of (mostly wooden) buildings near Wall Street. Historians estimate that 674 homes and businesses were destroyed, including the New York Stock Exchange, with damages totaling $26 to $40 million. Recovery, however, was rapid: 500 new buildings went up within a year, Shaw said, and the search for replacement office space caused land to double in value. In the wake of the fire, the city’s business district expanded from Wall Street to the rest of Lower Manhattan, which had previously been mostly residential. Historians say the fire’s destruction also prompted wealthy New Yorkers to start moving Uptown — which at that time meant Bond Street, Great Jones Street and Astor Place.

The Draft Riots of 1863

The Draft Riots of 1863Fueled by anger over the first federal conscription act and hardships caused by the Civil War, the Draft Riots brought days of rioting, looting and arson. More than 100 people died and some 50 buildings were damaged or destroyed by fire, Shaw said, including the Bull’s Head Hotel on 44th Street and the Fifth Avenue home of Mayor George Opdyke. Property damage was estimated at $1 to $5 million, he said. Perhaps more important for the city’s real estate market, the riots led to stricter regulations for tenement conditions. The Tenement House Act of 1867, for example, specified one water tap inside each building, one toilet for every 20 residents, and no occupancy by farm animals.

The General Slocum disaster

The General Slocum disasterOn June 15, 1904, fire broke out aboard the General Slocum, a steamboat that had been chartered by St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church for its annual picnic. Facing rotten life jackets and a crew untrained in emergency procedures, over 1,000 passengers died. Until 9/11, it was the deadliest day in the city’s history. Most of those on board were of German origin and hailed from the Little Germany, or Kleindeutschland, on the Lower East Side. Kleindeutschland was already on the wane when the fire struck, with upwardly mobile immigrants moving to pricier areas. But the disaster accelerated the rapid dissolution of the neighborhood, because survivors and victims’ relatives were unwilling to remain in an area so associated with tragedy. By 1910, the German community was virtually gone from the area, replaced by other immigrant groups. “It was really a unique tragedy [that] affected the social composition of a district,” said author and historian Edward O’Donnell.

The blackout of 1977

The blackout of 1977Lightning struck a Consolidated Edison substation along the Hudson River during a heat wave in the summer of 1977, prompting a massive power failure throughout most of the city. With the country facing an economic downturn and the city nearly bankrupt, vandalism and rioting broke out in poor neighborhoods, especially in Crown Heights, Bushwick and Fort Greene. When it was all over, 1,616 stores had been either looted or damaged, more than 1,000 fires were set, and 3,776 people were jailed. A Congressional study later put the damage at $300 million. The impact on the real estate market was long-lasting. “Insurance companies started to change their policies and stopped writing policies for businesses [in those areas], so these blocks never got rebuilt,” O’Donnell said. “As late as the mid-1990s, you could not find an ATM, bank, grocery store or theater in Fort Greene and parts of Harlem.”

Sept. 11, 2001

Sept. 11, 2001Killing nearly 3,000 people, the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, had a profound effect on the overall psychology and economy of the city, not to mention the real estate market. According to the Alliance for Downtown New York, some 14 million square feet of commercial office space in Lower Manhattan was damaged, more than 20,000 residents were at least temporarily displaced, and hundreds of shops and restaurants closed, some permanently. The repercussions were severe for the commercial market: Office leasing activity dropped some 40 percent in the area between 2001 and 2003, according to the Alliance. But as Manhattan’s economy improved in the mid-2000s, that trend reversed, and leasing activity increased 120 percent between 2003 and 2006. On the residential side, 9/11 had very little impact on the overall Manhattan market, according to appraiser Jonathan Miller. The median sales price for a Manhattan apartment was $420,000 in the fourth quarter of 2001, he said, and by the next year, it had grown to $450,000. Lower Manhattan, however, did see an exodus of residents after 9/11. “No one with children wanted to live here with the dust,” said Barbara Ireland, an associate broker at DJK Residential and longtime Battery Park City resident. By January of 2002, the value of a one-bedroom apartment in Battery Park City had dropped from around $400,000 to roughly $250,000, she said. “Sales in BPC have had a very slow climb back,” she added.