For its first development project in New York City, the Howard Hughes Corporation [TRDataCustom] set out to build a massive mixed-use hub in Lower Manhattan’s South Street Seaport — complete with a towering 500-foot condominium and a four-level shopping mall on the waterfront. But in the six years that Howard Hughes has controlled portions of seven buildings in the district, it has increasingly scaled back its vision for the area from a high-density wonderland to a midsize tourist trap.

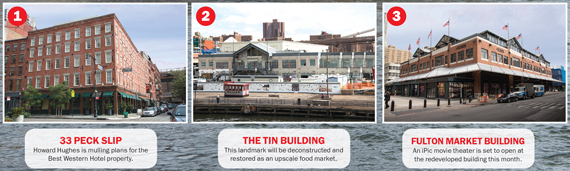

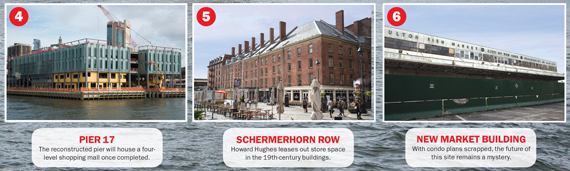

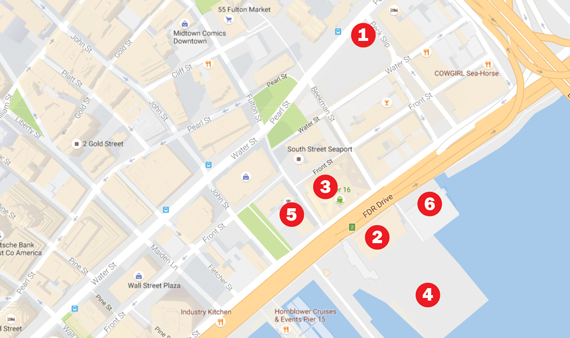

The Dallas-based development firm initially proposed a 52-story skyscraper with condo units and hotel rooms at the site of the historic New Market Building. Doing so, the company announced in 2015, would help fund the creation of affordable housing along the cobblestoned Schermerhorn Row, lined by 19th-century brick mercantile buildings that were later converted into storefronts. Howard Hughes also revealed plans to build its 300,000-square-foot glassy mall at Pier 17, a movie theater at the Fulton Market Building and an upscale food market in what is known as the Tin Building.

But the condo and hotel project was scrapped in December amid fierce community opposition, even after Howard Hughes had scaled back its proposal to 42 stories. Now the site’s future and the affordable housing component remain uncertain, along with other plans for the area, and the company is staying tight-lipped.

“There is much more to come. We continue to deliver on our plans to transform the Seaport District into the hub for cutting-edge cultural, fashion and culinary experiences,” a spokesman for the development firm told The Real Deal by email without elaborating on its plans for the district.

While Howard Hughes is moving forward with the redevelopment of Pier 17, the Tin Building and the Fulton Market Building, the Seaport has lost some of the luster that accompanies a large mixed-use development. And though the company has billed the waterfront as the city’s latest restaurant and entertainment mecca, much of its plans for the area remain a mystery.

“Mixed-use is always better than single-use,” said RXR Realty’s Executive Vice President Seth Pinsky, who served as head of the Economic Development Corporation at the time that Howard Hughes took over the waterfront. “The fact is, until the community and developer are able to come up with a plan that both sides can live with, we are going to have a less optimized South Street Seaport than we could have.”

“Mixed-use is always better than single-use,” said RXR Realty’s Executive Vice President Seth Pinsky, who served as head of the Economic Development Corporation at the time that Howard Hughes took over the waterfront. “The fact is, until the community and developer are able to come up with a plan that both sides can live with, we are going to have a less optimized South Street Seaport than we could have.”

Ye olde port

The South Street Seaport, which spans roughly 11 blocks, is considered Manhattan’s oldest neighborhood. As early as 1625, the area served as a landing site for boats stopping at the Dutch West India Company’s post at Manhattan’s south end. The area later evolved into one of New York’s busiest commercial hubs, still evidenced by the slew of 19th-century commercial buildings, including the trade houses along Schermerhorn Row.

The Seaport’s modernization became widely evident in the 1980s, when developer James Rouse introduced his famed “festival marketplace” to the area. That led to an enclosed shopping mall at Pier 17. When the three-story complex opened in 1985, then-Mayor Ed Koch told reporters that it was “one of the most important developments” to take place in his administration, according to a New York Times article published at the time.

Fast-forward roughly three decades, and the Seaport is embarking on its next reincarnation. Howard Hughes, led by real estate executive David Weinreb, took control over part of the Seaport in 2010. At that time, Howard Hughes had spun off from Chicago-based General Growth Properties during its bankruptcy proceedings and inherited some of the company’s real estate, including the Seaport.

GGP had controlled the property through a long-term lease with the city, which was transferred to Howard Hughes. Howard Hughes pays $1.5 million in annual rent and the lease is set to expire in 2072. Weinreb and his associates announced in 2012 that they would demolish the existing Pier 17 and build a new one in its place. Though the structure had largely been spared from damage during Hurricane Sandy, it had long been criticized for being outdated and blocking views of the waterfront. From there, the company’s vision for the district expanded to surrounding buildings and nearby development sites in a revamp of the area that the company estimated would cost $1.5 billion.

GGP had controlled the property through a long-term lease with the city, which was transferred to Howard Hughes. Howard Hughes pays $1.5 million in annual rent and the lease is set to expire in 2072. Weinreb and his associates announced in 2012 that they would demolish the existing Pier 17 and build a new one in its place. Though the structure had largely been spared from damage during Hurricane Sandy, it had long been criticized for being outdated and blocking views of the waterfront. From there, the company’s vision for the district expanded to surrounding buildings and nearby development sites in a revamp of the area that the company estimated would cost $1.5 billion.

In the last few years, Howard Hughes has both amassed and shed a considerable amount of land at the Seaport. The firm — which now has $6.2 billion in assets, with $4.6 billion committed to real estate investments — bought a development parcel at 80 South Street for $100 million in 2014 and another site at 173 Front Street for $24 million last year. The company got the necessary approvals from the City Planning Commission to transfer some 400,000 square feet of air rights to the adjacent sites to make way for a massive mixed-use tower on the two parcels.

But in April 2015, Crain’s New York Business reported that Howard Hughes was either seeking a partner or buyer for the sites. About a year later, Weinreb announced in a press release that the company had closed on the sale of the sites for $390 million to China Oceanwide Holding Group, which plans to build a 1,436 foot-tower with 441,077 square feet of residential space and 376,707 square feet for hotel, office or retail use. Weinreb said at the time that the company shed these sites to focus on its other projects in the district.

In November, Howard Hughes unveiled its plans for the 52-story condo and hotel tower as part of an additional 700,000 square feet that the developer wanted to add to its 400,000 square feet of development planned throughout the district. But a working group formed by local officials — including Borough President Gale Brewer, former Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Council Member Margaret Chin — opposed the project, due to its height, and the developer shaved 10 stories off the tower. A month later, the company halted all plans for the New Market Building site, which once housed the Fulton Fish Market.

The future of that site remains unclear, as do plans for Schermerhorn Row and 33 Peck Slip — a Best Western Hotel that Howard Hughes picked up last December for $38.3 million.

The company operates the retail along Schermerhorn and recently inked a lease with the Soho-based bookstore McNally Jackson, which will open a 7,000-square-foot store there next year. In addition to its affordable housing proposition, the developer had intended to bring a new four-story building nearby, but that proposal seems to be on hold as well. Howard Hughes currently has no plans for the New Market site and will reveal its designs for 33 Peck at “some point in the future,” the spokesperson said.

Ripple effect

While several of the company’s original plans have been put on ice, other developers in the area believe the retail upgrade alone will encourage further residential activity in the district.

“We think that the Seaport will become a premier residential neighborhood over the next few years,” said Jonathan Landau, CEO of Fortis Property Group, which is building a new condo tower in the area currently branded as 1 Seaport. “Howard Hughes is doing an incredible job of re-creating the retail experience at a very high level, which is just going to make it better and easier to develop residential projects out there.”

But the ambiguity surrounding the other parts of the Seaport’s redevelopment has been a source of criticism for community activists. Michael Kramer, a former member of the working group and part of the Save Our Seaport advocacy group, said that Howard Hughes has released details for the waterfront piecemeal, instead of providing a comprehensive master plan.

“The community is not having a dialogue,” Kramer told TRD. “We’re clearly suspicious about what plans have been announced and what plans have not been announced.”

Pinsky of RXR said the city and Howard Hughes had actually completed a master plan but that community members and elected officials had made it clear they wouldn’t support it. He said that removing the more controversial elements of the project, including the waterfront condo tower, allowed the less contentious components, such as redeveloping the pier, to move forward.

The new Pier 17, which topped out in March, is expected to be completed next year and has well-known restaurateurs David Chang and Jean-Georges Vongerichten anchoring the space. The Landmarks Preservation Commission in March approved plans for the Tin Building, which will feature an upscale food market by Vongerichten.

David Weinreb

Howard Hughes will deconstruct the building and then “painstakingly” rebuild it 18 feet south of its current location so that it is set back from Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive and lifted out of the flood zone, according to the company. The redeveloped Fulton Market Building will soon be home to an iPic movie theater and a 13,000-square-foot 10 Corso Como, an Italian retailer that incorporates cafés and art galleries in its stores. The building is set to open this month.

Howard Hughes plans to self-fund its Seaport projects with its own equity and forgo any construction loans, Weinreb revealed in May. The publicly traded company had $2.5 billion in equity as of its most recent quarterly report in June.

“We didn’t want to have the burden of a lender who was going to have various requirements about, you know, when you were going to be leased, the timing, etc.” Weinreb said, during a panel at WeiserMazars’ Commercial Real Estate Summit. “Because when you’re resuscitating an asset, often the best decisions are not signing a lease, not doing something, just being patient. And when you have a lender that’s behind you, they often are pressuring you to make decisions that are not good decisions for the long term.”

The pier still faces competition to the northwest from Brookfield Place and the Santiago Calatrava-designed Oculus. However, Brad Gerla, an executive vice president at CBRE, said that there’s enough demand in the area for retail and eateries — especially along Lower Manhattan’s quieter east side. He also noted that the Seaport offers an alternative lunch destination to workers in the area.

“I work Downtown. I can’t go to Brookfield place every day. I can’t go to Calatrava every day,” Gerla said. “If it’s going to be more retail-focused, it’s only going to help the community.”