UPDATED, 12:04 p.m. Oct. 16: Gentrification may be synonymous with Brooklyn at this point, but the seemingly unstoppable phenomenon has yet to overtake Borough Park.

UPDATED, 12:04 p.m. Oct. 16: Gentrification may be synonymous with Brooklyn at this point, but the seemingly unstoppable phenomenon has yet to overtake Borough Park.

The Orthodox Jewish enclave nestled in the borough’s southwest corner has largely shielded itself from high-rise towers and large commercial hubs. In addition to limited buildable land, there’s a shared aversion to large-scale development among Borough Park’s influential residents, industry sources and community leaders told The Real Deal.

That aversion has held strong over the years — despite several active developers and real estate investors living there. But opinions vary on whether it’s best for the neighborhood and how long it can last. Now, concerns about overdevelopment are running headfirst into a stark need for more housing as the area’s population continues to grow.

“In our community, children want to live near their parents and grandparents and sometimes great-grandparents,” said state Assembly member Dov Hikind, who represents the neighborhood. “There’s a real effort to make that happen, and it’s become pretty much impossible because housing is at a premium.”

The only spot Hikind cited as having potential for development is a stretch of land that runs roughly between 60th and 62nd streets and 9th and 15th avenues near local train tracks. But despite conversations about building there, efforts have yet to get off the ground.

“There have been attempts, discussions, but the truth is we haven’t gotten to first base yet,” Hikind said. “That doesn’t mean it isn’t going to happen. But that is the only area, realistically, where you could actually build a tremendous amount of housing.”

City Council member David Greenfield, who also represents Borough Park, said the lack of available land has made it difficult to address the biggest complaint he hears from his constituents: that the area desperately needs more affordable housing for young residents and working-class families.

Greenfield noted that a typical development in the neighborhood will involve someone tearing down a one-family home and replacing it with five- or six-story condominiums. But he said bringing large projects to Borough Park comes with problems of its own.

“Even if you could find land that’s available to build at the scale you need to be affordable, you’d have to build much larger than [what] the community is used to,” he explained. “And there is resistance to that.”

Inevitable change

Others argue it’s simply a matter of time before more large-scale residential projects come on line.

“Eventually, they have to,” said Melissa Leifer, a Keller Williams agent who works in Manhattan and Brooklyn. “It’s hard to find lots or multiple houses next to each other that will all sell. In the next couple years, though, I would absolutely think that there would be more development. I have developers I work with now who are actively looking there.”

One big project that has recently gone up in Borough Park is the Hamilton, a 92-unit luxury rental property at 968 60th Street that opened last year. The property was built by Halcyon Management Group, the same real estate firm behind the Plex in Crown Heights and 101 Bedford in Williamsburg — both upscale apartment buildings.

The Hamilton’s website includes a “FOMO alert,” using the common acronym for “fear of missing out,” to warn people that the building’s remaining apartments will go quickly. Rents at available units ranged from $2,150 to $4,000 per month, compared to Borough Park’s median asking rent of $1,750, per StreetEasy. But despite the higher rents and amenities that include a game room and PGA golf simulator, Halcyon Management’s Yoel Sabel told TRD through a spokesperson that his firm doesn’t want the project to change the neighborhood.

Borough Park also houses Maimonides Medical Center, which opened as a dispensary for the poor in 1911 and is now undergoing a $100 million, 140,000-square-foot expansion. The hospital’s new seven-story Medical Arts Building will include more than 100 rooms for exams and consultations as well as physician offices.

The neighborhood will likely see at least two other large projects in the near future — both from real estate owners based in Brooklyn. Last year, Bernard Jacobowitz’s Davbel Properties paid $29.5 million for a 1.5-acre development site at 886 Dahill Road that has already been approved for a 10-story apartment building with 171 units. And the Leser Group, run by developer Abraham Leser, is planning a roughly 250,000-square-foot residential building at 1570 60th Street. That project will contain 128 market-rate apartments at an average size of about 1,600 square feet and is scheduled for completion next summer.

As of now, projects like these are the exception for the neighborhood rather than the rule, said Leser Group partner Barry Katz, who also pointed to the lack of available space to build. “It’s not often that you’ll find a nice-sized piece of land in the area,” he noted.

But no neighborhood planning in New York is written in stone, and Brooklyn Community District 12 — which encompasses Borough Park, Kensington, Ocean Parkway and Midwood — has seen at least six rezoning initiatives go through in the past 15 years. That includes one announced in 2005 for a six-block area along 37th Street to allow for more housing and one in 2013 for the lot where the Leser Group’s project will go up.

For significantly more development, the neighborhood would require a larger rezoning, said Patrice Derrington, director of Columbia University’s Center for Urban Real Estate. For now, she said, the area will remain an unlikely candidate for that.

“It’s probably regarded as being in too good condition to knock down buildings and put up big ones,” she said. “And you’ve got community groups that are … pretty well established.”

The lack of housing in the neighborhood has reached a point where some residents have started moving out, especially young adults looking to start their own families, according to Greenfield and others. Some of those residents have taken to Rockland County and parts of New Jersey.

Barry Spitzer, district manager of Community Board 12, argued that having people leave is a better solution than encouraging more development, since Borough Park is grappling with infrastructure issues that new large-scale housing would exacerbate.

“God blessed this community with a lot of children and families,” he said. “But with the children come the school buses, and with the school buses come the traffic, and with the traffic, we have to redo the entire sanitation routes here.”

By the book

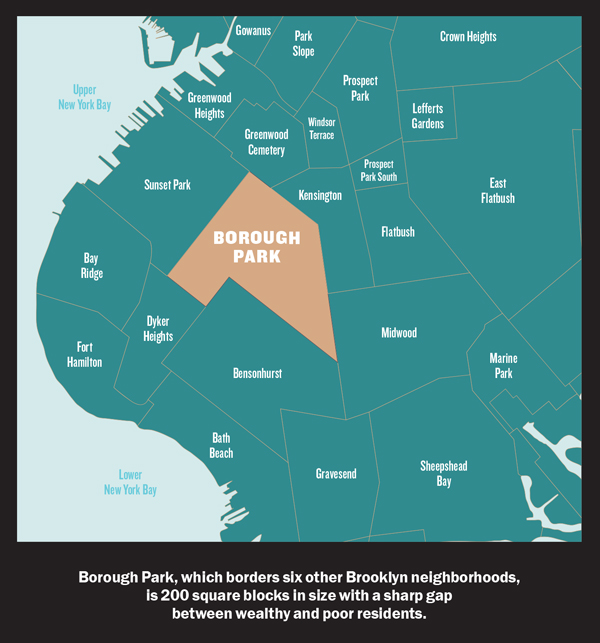

Borough Park has one of the largest Orthodox Jewish populations in the country, and though it’s only 200 square blocks in size, it contains more than 300 religious institutions, according to StreetEasy.

This adds another challenge to building in the neighborhood — particularly when it comes to planning and leasing retail space, said one developer who is active in Brooklyn and who previously owned land in Borough Park. The developer, who asked not to be named, noted that most stores will close on Saturdays for the Sabbath and will not experience the typical windfall that retail enjoys around Christmas.

The centrality of Judaism in Borough Park also contributes to the neighborhood’s severe wealth gap, with 32 percent of residents living in poverty and 63 percent of residents rent-burdened, per city statistics from 2015.

While income inequality has been prevalent in New York for centuries, Borough Park’s poor and wealthy residents live in a remarkably integrated way. That’s largely because many want to be near their local synagogue and rabbi, Greenfield explained.

“You’ll literally have a millionaire living next to somebody who’s on food stamps,” he said, “The reason it’s a unique feature of what you perhaps don’t see in a lot of other places in New York City is because they’re living in the same community really for religious access reasons.”

Borough Park’s wealthier residents include real estate investor David Werner, known for his $1.5 billion purchase of 5 Times Square in 2014, and Clipper Equity founder David Bistricer, who purchased the Sony Tower with Joseph Chetrit for $1.1 billion in 2013 before selling it three years later to Olayan America.

Bistricer said Borough Park’s residents have different amounts of money not unlike other parts of the city and told TRD that he enjoys living in the neighborhood because of how familiar he is with it. “I just grew up here,” he said. “For me, it’s very convenient. I work in the neighborhood.”

Josh Zegen, co-founder of the Manhattan-based real estate firm Madison Realty Capital, said Borough Park’s insularity can make it difficult for developers to break into the neighborhood without a strong community connection. “Even though I’m Jewish, in many ways [I] would have to partner with someone in that community to be able to really develop to what the community would want,” he said.

But Zegen’s firm is very active just one neighborhood over in Sunset Park. Madison purchased a pair of vacant warehouses there last year for $37 million and acquired the Brooklyn Whale Building in 2015 for $82.5 million.

He said Sunset Park’s large stock of industrial buildings and the neighborhood’s diversity have made it more appealing for large-scale development than Borough Park — despite their shared border along Ninth Avenue. Sunset Park, for instance, has attracted big national firms, including Amazon, the Gap and Time Inc., which Zegen said would not be as good a fit for Borough Park.

“It’s not as much of a global kind of market,” he said. “The community wouldn’t necessarily want that tenancy there.”

While Borough Park is still largely defined by its Orthodox Jewish community, though, it’s gradually diversifying. The neighborhood is 75.6 percent white, per 2014 Census Bureau data, while 12.9 percent of its population is Asian and 10.3 percent is Hispanic. As Brooklyn’s Chinese population continues to spread south, that demographic has become a greater presence in the area, Leifer of Keller Williams noted.

“Other than that, it’s [still] very isolated,” she said. “It’s not like you’re getting a lot of hipsters saying, ‘Maybe I’ll buy a house in Borough Park.’”

Peter Matheos, an investment sales broker at TerraCRG, said that will soon change, pointing to the area’s many transportation options, which include the N and D trains, several bus routes and the nearby ferry at Industry City.

“Borough Park has the potential to be the next place for young professionals to live, work and play,” he said in a statement. “With continued development along the Sunset Park waterfront, the expansion of Maimonides Hospital and more plans for hotels [in the area], the immense job growth will create a demand for new, trendy residential options.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story misstated Barry Spitzer’s job title. He is the district manager of Community Board 12, not the chair.