All you need to know about Shaya Prager and Fort Worth’s tallest building, Burnett Plaza, is that he bought it, he lost it and he got sued over it.

But this drama was just the tip of the iceberg.

Since May, the New Jersey investor’s saga has evolved into a national mess of intersecting lawsuits and loan defaults. They share a common thread: trying to parse how and where Prager built a multibillion-dollar real estate portfolio out of almost nothing, and whether any of it is real.

During the last five years, Prager, the owner of Opal Holdings, and his business associate, Katherine Cartagena, swept through the country and bought billions of dollars’ worth of office properties. Prager then used an uncommon ownership structure involving ground leases to essentially double his collateral and take out loans that far exceeded the value of the real estate.

At many of the sites, Cartagena appeared to purchase the property and lease the ground to Prager. Both then took out substantial mortgages against their separate interests.

In total, they borrowed more than $3 billion, often from small regional banks and credit unions across 11 states.

UMB Bank was the trustee on nearly $1.2 billion worth of credit tenant leases, which is financing available to landlords with high-profile or long-term tenants. The bank said in a statement that it was retained by debt arrangers, not Prager.

Prager’s defense lies in the parsing of words.

His lawyer denied that the landlord and tenant entities were “affiliates” (per the definition in the loan agreement) in the case of Burnett Plaza. Prager was upfront with lenders about the potential for “common beneficial ownership,” he said.

His lenders, however, contest this.

They say Prager lied to score loans they never would have provided had they understood his ownership scheme.

From the perspective of his lenders, Prager, the ground lease tenant, borrowed money against his ground leasehold while the property’s landlord separately took out a mortgage against the property.

What they’re now realizing is that the transactions weren’t so separate.

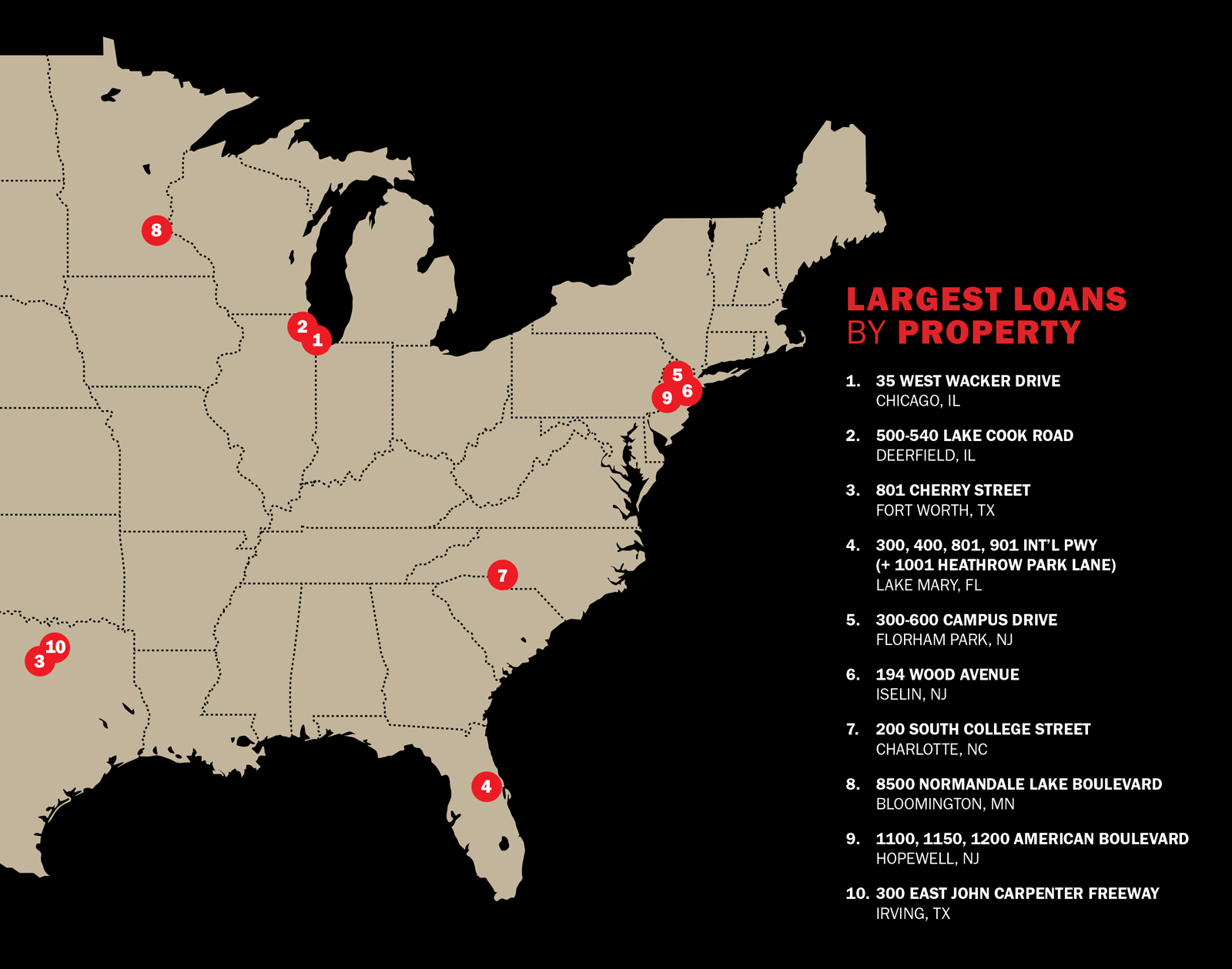

As lawsuits and foreclosure bite off chunks of his portfolio, we mapped out his borrowing activity — which spans the country but is concentrated in his home state of New Jersey — to give the full picture of his alleged scheme.

Foreclosure Whac-a-Mole

Pinnacle Bank, the mezzanine lender at Burnett Plaza, first called out the ethics of Prager’s complicated ownership structure in a lawsuit that a North Texas construction company brought against Prager for a $1 million debt.

The Nashville-based bank claimed that Prager lied about his affiliation with the landlord of Burnett Plaza to score an $83 million loan. It also claimed Prager wasn’t paying his mortgage. Pinnacle foreclosed on the property, and in May, won back the tower with a $12.3 million credit bid.

The Whac-A-Mole of foreclosures next popped up in Minneapolis.

In the summer of 2022, Prager dropped $366 million on Normandale Lake Office Park, a five-building, 1.7 million-square-foot complex in Bloomington, Minnesota.

Between the five buildings, the landlord entities borrowed $186.1 million. The ground lease tenants borrowed $218 million. That’s a total of more than $404 million.

In March, Wings Federal Credit Union, which lent $41.34 million to the ground lease tenant of one of the buildings, sued Prager for defaulting on the loan.

The court granted Wings’ request for a receiver in April, but the Minnesota-based credit union is still trying to recover the difference between the value of the building and the amount of the loan. There’s a trial set for May 2025.

Someone familiar with the Wings deal reiterated Pinnacle’s claims: the borrower represented that the landlord and ground lease tenant were not affiliated.

In June, Prager’s lawyer called Pinnacle Bank’s accusation “baseless” and denied that the landlord and ground lease tenant are affiliates.

Prager’s camp acknowledged his frequent use of the “transaction structure” for the first time in an October statement. He still claims that the lender was aware of the situation.

“This transaction structure has been used more than two dozen times by entities owned by Mr. Prager, and yet Pinnacle is the only party involved in one of those transactions that claims it was not aware of the potential common beneficial ownership between the landlord and tenant,” Prager’s spokesperson Steven Goldberg wrote in an email.

Wings disagrees.

Moving money

Lenders previously in the dark have been catching on.

Two recent loan default lawsuits — one filed by Wells Fargo in Florida and the other by Columbia Pacific Advisors in Minnesota — have cited The Real Deal’s July 2024 story explaining Prager’s “common beneficial ownership” move.

His defaults are “part of an unfortunate pattern undertaken by Prager and his companies, including Opal, to avoid the consequences of their overextending themselves during a commercial property ‘shopping spree,’” Wells Fargo wrote in a request for a receiver to be appointed for Prager’s Lake Mary properties.

As courts determine how to foreclose on properties with this complicated ownership structure, lenders claiming Prager defaulted on loans are eager to get control of these properties’ cash flow as soon as possible.

That’s because some believe Prager is diverting income — which is supposed to be used to pay the loans — back to himself.

In the case of an Ohio industrial property, Wells Fargo claims it caught Prager in the act.

The bank explained the allegations in a lawsuit filed in Florida claiming Prager defaulted on a $79.7 million loan connected with an office building in Lake Mary, a city in Florida. Wells Fargo is also the lender on an industrial property Prager owns in Ohio, and it has access to the operating account for its ownership entity, called 20001 Euclid Industrial.

The account issued three six-figure checks between July 30 and Aug. 1.

Euclid wrote a check for $125,000 to “Riverwood Cleaning” on July 30, a check for $125,000 to “Riverwood MP” on July 31 and a check for $120,000 to “Riverwood MP” on Aug. 1.

It may have been harder to figure out what Prager was doing if the addresses for Riverwood Cleaning and Riverwood MP on the checks were different from the address on file for the Euclid LLC: 212 Second Street #104, Lakewood, New Jersey.

“It is Wells Fargo’s belief that Prager is siphoning money out of Euclid’s account in an attempt to place the funds beyond the bank’s reach,” the bank said in its request for a receiver for the Lake Mary properties.

Prager did not comment on this claim.

Columbia Pacific Advisors made a similar accusation in its August lawsuit against Prager in Minneapolis: “Borrower has been diverting rents from the Premises for uses unrelated to maintenance of the Premises and Ground Lease despite such rents being the collateral of Lender.”

Out of thin air

Since Prager lost control of Fort Worth’s Burnett Plaza, other properties have fallen like dominos.

Just 15 miles away in Arlington, Texas, Prager lost a four-building office complex to foreclosure after defaulting on a $40 million loan from Pinnacle Bank.

An auction is scheduled for 8500 Normandale Lake Boulevard (of the Normandale Lake Office Park buildings) in November after Columbia Pacific Advisors foreclosed on the property, claiming Prager defaulted on a $65 million loan.

Prager is also facing as-yet-unresolved loan default lawsuits from Webster Bank, which alleges Prager defaulted on a $62 million loan for American Metro Center in Trenton, New Jersey, and a $91 million loan for 300-600 Campus Drive in Florham Park, New Jersey.

In suburban Chicago, Prager isn’t just accused of defaulting on a $106 million loan from Unify Federal Credit Union. He’s on track to face sanctions from Lake County Judge Daniel Jasica for failing to comply with the judge’s orders to turn over more than $2 million to the property’s receiver.

That’s to say nothing of the aforementioned lawsuits involving Pinnacle Bank in Texas, Wings Federal Credit Union in Minnesota, Wells Fargo in Florida and Wells Fargo in Ohio.

Prager’s tumbling house of cards leaves lenders with many questions, like: What’s Prager doing with the income from these properties? And, who signed off on these deals?

The most important one might be: Did the equity Prager brought ever really exist? Or, was it money from another transaction, concocted out of thin air?