As Sol Goldman’s loved ones sat shiva for him in late 1987, the matter of who would lead his vast empire loomed as large as the Chrysler Building.

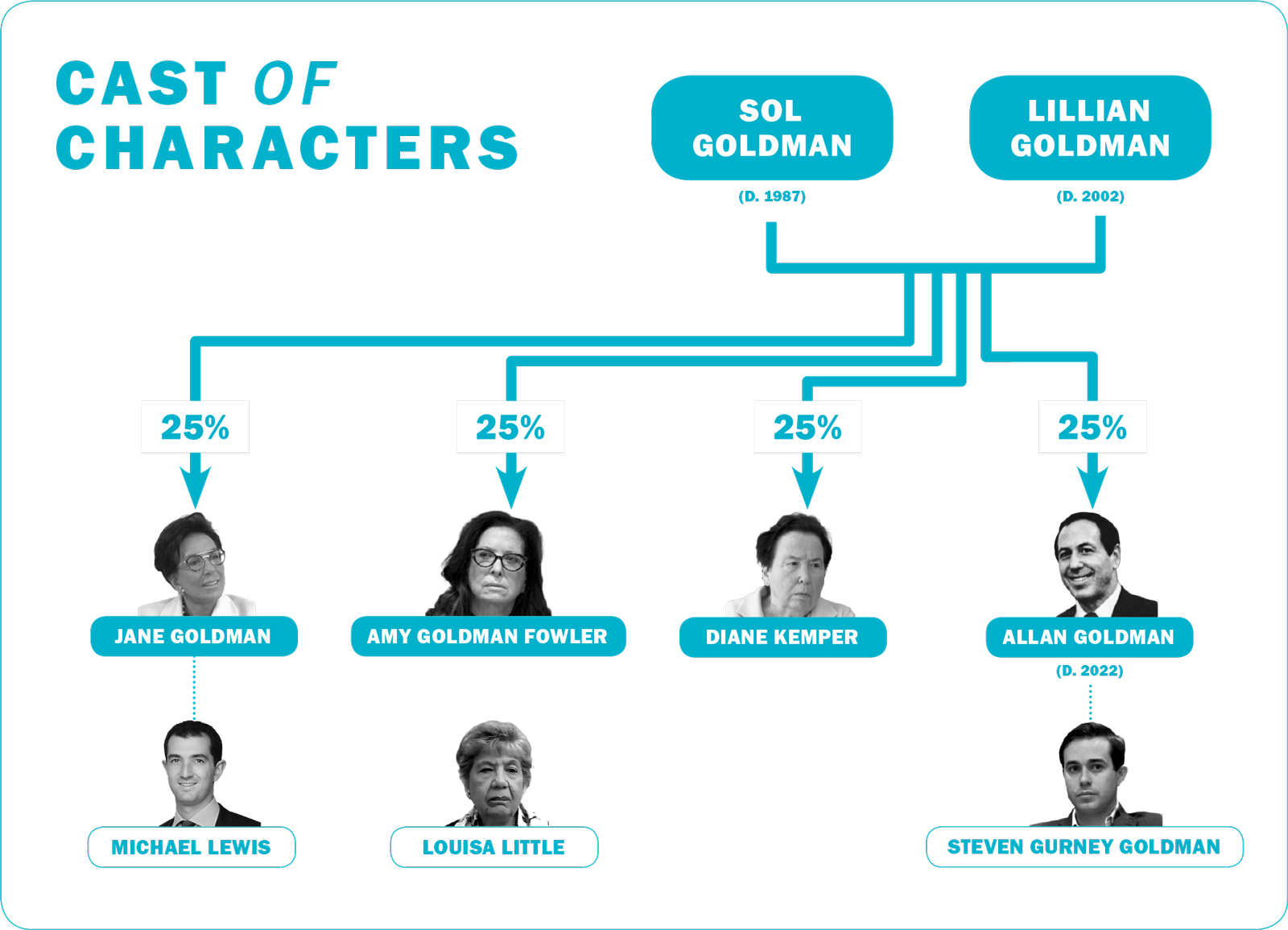

Goldman, widely acknowledged as the most successful real estate investor of his time, had spoken with each of his four adult children about his will, which named his youngest daughter Jane and her brother Allan as co-executors of his estate.

Sitting in a Delaware courtroom four decades later, Jane testified that at the shiva her sister Amy, who had pursued a career outside the family business, expressed relief that she wasn’t the one to carry that responsibility.

“My father went over the will with each of his children. So we all knew what was happening,” Jane recounted earlier this year at a trial concerning a key piece of the Goldman family business. “I remember specifically Amy being glad that it wasn’t her.”

Amy, however, emphatically denies saying anything of the sort at that time.

“Absolutely not,” she said, describing the shiva as a very sorrowful period when talk of business was verboten. “I remember overhearing a cousin who was talking about family business. And it just absolutely disgusted me.”

In the 35 years following Sol’s death, the Goldman family maintained a quiet — if delicate — prosperity. The adamantly private family has avoided the limelight that comes with running one of New York’s largest real estate portfolios. (These things are tough to put a figure on, but it’s been said to be worth anywhere from $4 billion to $16 billion.)

But that peace was shattered two and a half years ago when Allan died at age 78 of complications from Parkinson’s disease. Since then, his 33-year-old son, Steven, and Amy have challenged Jane’s control of the family business in a bitter affair their attorneys likened to a real-life version of the HBO show “Succession.”

Jane and her sister Diane now claim their two disgruntled relatives are trying to extort money they’re not entitled to.

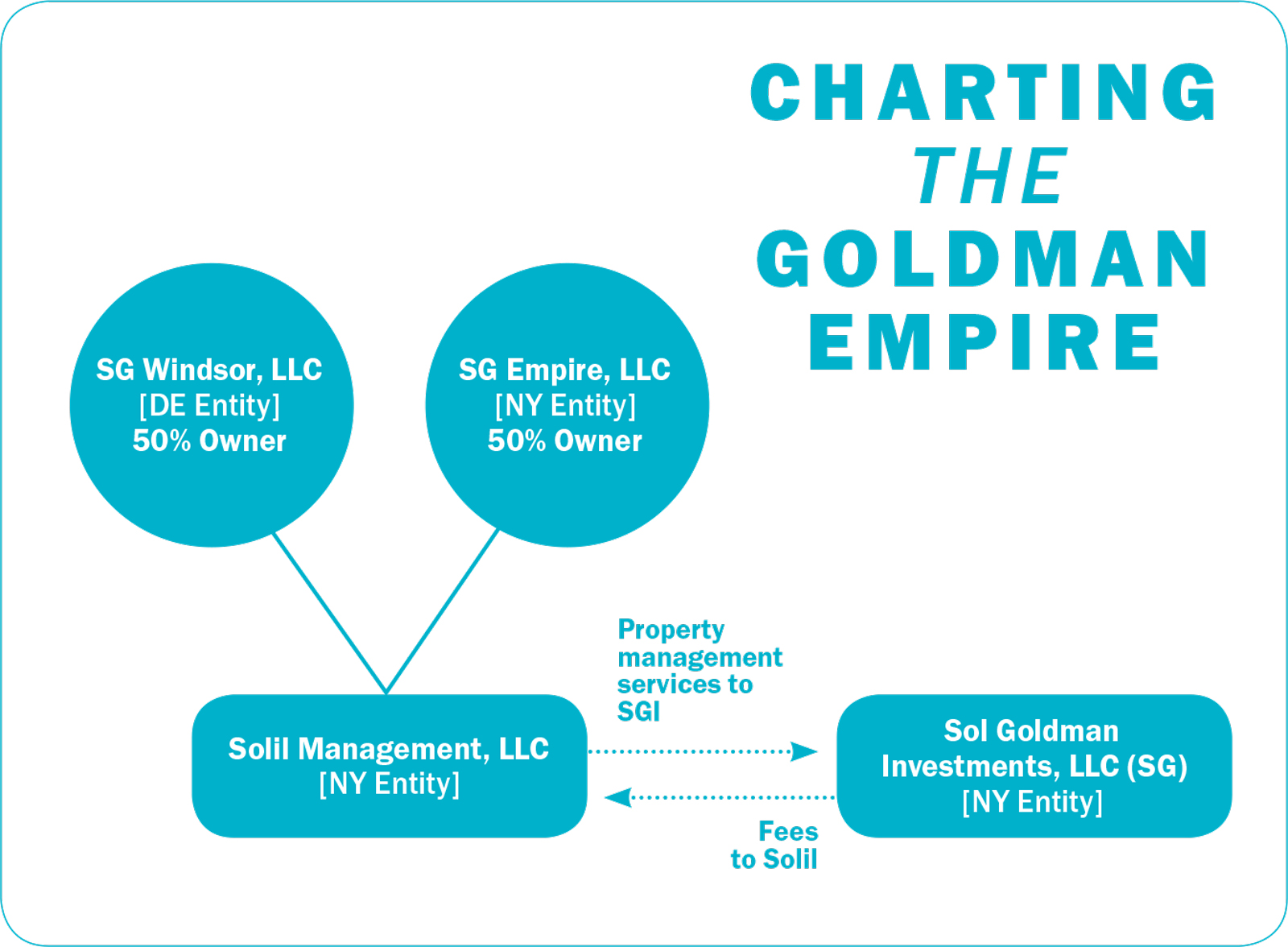

The dispute gets at the beating heart of the Goldman enterprise: a labyrinth made up of hundreds of entities — trusts, estates, LLCs and holding companies — some of which spell out who’s in charge and what kinds of major decisions they can make, and others that don’t.

The fight over control, pieced together from previously unreported trial testimonies, court documents and interviews with people around the family, offers a rare look at the drama surrounding handovers inside family firms. Few dynasties can withstand the growing pains as a single stakeholder multiplies into dozens of family members, all eager to live out their ambitions and pursue self-interests, over the course of just a handful of decades. To stick it out, they may need more than a competent steward. They have to be willing to fight a constant battle against entropy.

For all those years the Goldmans ran their business casually with little need for things like official titles or bylaws; it was held together by the kinds of unspoken pacts familiar to anyone with siblings. That status quo was good enough for everyone involved, until it wasn’t.

“The record suggests that the Goldman family has not always observed entity formalities by maintaining a strict division between the property manager and the property owners,” Delaware judge J. Travis Laster wrote following the family’s trial in May, words that will affect a concurrent legal battle in New York. “Who does what in what capacity seems fluid.”

The Golden days

Sol Goldman was born in 1917 in Brooklyn. He worked at his parents’ grocery store and was entrepreneurial at a young age. At 16, he started buying up foreclosed properties in the neighborhood.

“I think they were $500, and he would borrow $50 from the liquor store and $50 from the pharmacist,” Jane chronicled from the Delaware witness stand. “That’s actually how he met his partner, because he was going around the neighborhood and collecting money. He loved to buy buildings. He loved real estate. And he continued to do it even while he was in the supermarket.”

Goldman built up a portfolio of 600 properties that once included the Chrysler Building. He and his partner Alex DiLorenzo were followed by rumors that they were involved with the mob, which they denied. After DiLorenzo died in 1975, his son and Goldman avoided a protracted dissolution by splitting their properties up via a series of fateful coin tosses.

Today, the Goldman portfolio includes the ground under major office buildings like 1407 Broadway and 475 Park Avenue South, as well as under the Peninsula and Mark hotels. It also owns outright several large apartment buildings, such as 145 East 16th Street and 96 Fifth Avenue.

When Sol died on October 18, 1987, at age 70, his $1 billion estate was the largest ever to enter New York Surrogate’s Court, which oversees the execution of wills. It ended up there because in 1983 his wife of 43 years, Lillian Goldman, moved out of their suite at the Waldorf-Astoria and filed for divorce. Sol promised that if she came back he would give her a third of his fortune when he died, scribbling out an agreement on a yellow legal notepad.

This contradicted Sol’s will, which put a number of properties into a trust from which Lillian could draw income but not own. When Sol died his children contested their mother’s claim to the one-third of the portfolio; the surrogate’s court famously ruled that the agreement on the yellow pad held up. Lillian died in 2002 and a central issue in the feud is that her estate, which includes a large portion of the Goldman properties, has never been settled.

Jane revered her father.

“Without getting mushy or anything, my father was my idol,” she said. “When my father was alive, the world was black and white; and after he died, it became gray.”

Jane is the youngest of Sol and Lillian’s children, but she was the one most involved in the family business.

Allan, the oldest, cycled in and out of the business but was forced to work remotely during the last 20 years of his life because of Parkinson’s. The eldest daughter, Diane (known as Deedee), worked in the company’s residential leasing department. But she suffers from a disorder called macular degeneration that affects her eyesight so much she can’t read documents and lives with Jane. Amy worked at the company part-time early on but stepped away to pursue a career in psychology.

Jane started going into the office as a child, answering phones. She went to work full time at age 22 beginning in residential leasing, learning other aspects of the business like sidewalk repairs, wallpaper changes, paint jobs, HVAC systems, local regulations, employee insurance, legal and so on.

She picked up some of Sol’s edicts, like never subordinate your position and never sell a group in packages. She watched her father’s views on borrowing change later in life as he took his portfolio of 20-80 equity-to-debt and inverted the equation.

Today, the company has very little debt.

“Literally, we could pay it off tomorrow if we had to,” said Jane, who at 69 wears a short haircut and round tortoiseshell eyeglasses.

When it came time to name his successors, Sol created a triumvirate: Jane and Allan would run things along with a third person from outside the family who could help them. Jane chose a longtime employee and trusted confidante named Louisa Little, whose husband had been a superintendent on one of the family’s buildings.

When Little was about 19, her husband asked Sol if there was a place for her in the business. She became indispensable.

“She’s really one of these people who are very capable at whatever the task is, and she has a lot of knowledge that none of the other Goldman family members have,” Jane said, rattling off Little’s expertise in areas like boilers and gas, such as the difference between No. 2 and No. 4 oil.

“I trust her completely,” Jane added. “My father trusted her completely.”

After Sol died, the structure of the business got more complicated, as the sole proprietorship ballooned into a sprawling organization made up of individual properties placed into LLCs. Today the locus of the Goldman family business is Solil Management (a portmanteau of Sol and Lillian), which handles the day-to-day operations of the properties held in various entities.

For a long time the Goldman siblings were in near-perfect harmony. None of them could recall a time when they had any major disagreements on business issues.

In 1988, Jane, Allan, Amy and Diane hammered out a written agreement stipulating that they’d share any benefits they may receive from their mother equally among the four of them — or, in the case any of them died, their descendants.

It was in keeping with the way Jane and her father saw eye-to-eye on running the business.

“It was his hope — and at the time the other family members’ hope — to keep it together for ourselves and the future generations.”

Under strain

In January 2022, Allan succumbed to his long battle with Parkinson’s. He died of multiple organ failure at a hospital in St. Petersburg, Russia, where he had been brought by his caretaker.

(His son Steven is suing the caretaker, Natalia Vostrikova, accusing her of manipulating his father to get a $2 million inheritance.)

Steven and Amy say Jane used Allan’s death as an opportunity to seize power. They allege she coerced Diane to cede control of her branch of the family business and designate Jane’s son, Michael Lewis, as Diane’s successor, instead of her own daughter, who is not in good health.

They also claim Jane sidelined Amy by excluding her from key management decisions — informing her only after the fact. And they say she hired and fired outside advisers in order to consolidate her “death grip” on the company.

“Look, there were supposed to be votes. There have never been votes. There have never been meetings. Nothing. But if there were to be a vote, I would be outgunned two to one.”

“She has frozen out relatives with equal claim to the business in an effort to seek exclusive control for her own family branch, with the apparent intent of seizing the entire business to hand it over one day to her youngest child to the exclusion of Sol’s other lineal descendants,” they claim in the New York lawsuit.

Jane denies this, and in turn has accused Steven and Amy of trying to extort money from the family business.

“[Steven and Amy] begin the complaint by comparing their allegations to the critically acclaimed television series ‘Succession,’” attorneys for Jane and Diane wrote. “The comparison fits in one respect: both are works of fiction.”

A spokesperson for Jane said her son Michael is an “accomplished and trusted nephew” who agreed to represent Diane’s branch when she asked him to.

Allan’s death coincided with a pivotal moment for the Goldman affairs. About 14 years earlier the four siblings had set up a system by which they could cash out their stakes starting in 2022 via put options, which grant them the right to sell their shares back to the company at a specified price.

That price is determined by an appraisal of the Goldman properties: The higher the appraised value, the more the company has to pay the family members cashing out, and vice versa.

Steven and Amy were offered the right to receive $91 million each to redeem 5 percent of their respective interests in one of the family entities, court documents show. But they feel the appraisal was flawed and are objecting to it — a main point of contention in the family feud.

Another conflict came from Steven’s desire to step into his father’s shoes.

When Allan died, Steven was away at business school with two months to go until graduation. Jane said Steven told her he would leave school early if she made him a manager at one of the property owning entities, pointing out that he was around the same age she was when Sol died and she took the reins.

Jane said she had taken that responsibility out of necessity. She thought Steven was too young, noting that her own similarly aged son is gaining experience working at Blackstone. She would welcome him back to the company after school, she said.

“We didn’t feel he was ready. But we wanted him to come back,” she said. “When he left that day, I assumed he was coming back. He certainly left me with the impression that he would be returning.”

Steven’s account differs. He said he didn’t offer to return to Solil in exchange for a manager role. Whatever was said, it wedged both sides further apart.

“Jane felt that because she remained at the helm, there was no reason to integrate the next generation so quickly,” wrote Laster, who has overseen many high-profile cases during his 15 years on the country’s most influential business court. “Steven did not like that answer, and his relationship with Jane came under strain.”

Hostages, blackmail & bluffs

Jane’s treatment of Steven didn’t sit well with Amy, who saw the math had become stacked against her.

Following Allan’s death, major decisions would come down to a vote by Amy, Jane and Louisa Little, who was viewed as loyal to Jane.

“Look, there were supposed to be votes. There have never been votes. There have never been meetings. Nothing,” Amy said. “But if there were to be a vote, I would be outgunned two to one.”

In the heat of the disagreement over the appraisal, Amy experienced what she called a “watershed moment” with Jane in February of 2023 — about a year after Allan’s death.

According to Amy’s telling, one day Jane asked if the two could get together to talk about the Gramercy Park Hotel, which Solil had taken back from Aby Rosen the previous summer after he defaulted on his ground lease. Jane said there was an offer on the table for the lease. Amy responded that they needed to consult with the various family entities involved in the property.

Jane disagreed. “She said, ‘Look, I don’t need your permission. I’m going to do it anyway,’” Amy recounted.

By this time there had been talks about splitting the properties up among the four branches of the family, which would require Jane to finally settle their mother’s estate. When Amy turned the conversation to the long-simmering Lillian issue, she got nowhere fast.

“[Jane] basically conditioned the distribution of those assets on my consent to drop my opposition to the appraisal,” Amy said. “I said, No way in hell. You are not going to hold our family hostage.”

The conversation got out of hand, according to Amy, who said Jane slammed the door and went away screaming so loud that she could be heard in the hallway.

“It just devolved,” said Amy. “She was screaming, and she was actually spitting mad, and I’ll never forget it.”

Jane’s spokesperson said Amy’s recollection of the encounter was “way off base” and she was only interested in demanding a cash distribution from Jane.

About a month after that meeting, Amy, Steven and Jane entered into a standstill agreement to work out the logistics of partitioning the properties.

That seemed to produce a few months of relative calm, but when the agreement expired in September 2023, Steven and Amy pressed their issues again. They said they got no response from Jane, and in November they filed a pair of lawsuits: one in Delaware contesting control of a key LLC in the Goldman empire and another in New York challenging the appraisal.

The unpleasantness went on.

Jane described a “sordid” interaction she had with Steven a few weeks after he asked to be named a manager.

“He said, ‘I have information, which I’m not prepared to share with you, but it’s about you, and if you don’t take my 25 percent share of the company and give it to me, I’m going to tell Amy and you’re going to look very bad, and you don’t want that,’” she testified in court.

Jane said Steven never revealed the information, but she felt he was implying she’d done something wrong and was attempting to blackmail her. After that, she said she couldn’t see working with him the way she had worked with his father.

“I don’t like his ethics,” she said. “He would not be a good partner for me. It just would not work.”

When asked by his lawyer about the incident, Steven said the information he was referring to simply had to do with the appraisal.

“At that point there was information that I had received from employees at Solil about how the appraisal had been improperly conducted, about how she was depressing values related to it,” he said.

“We had talked about public lawsuits not being good for the estate, but I never threatened her or blackmailed her,” he added. “That’s ridiculous.”

Judge Laster said he thought Steven testified credibly about wanting to settle the litigation, and that Jane’s reaction seemed overblown.

Jane thought her nephew was bluffing.

“I think he’s, you know — he was a professional poker player for a while.”

Poker face

At 33 years old, Steven Gurney-Goldman could be mistaken for someone a decade younger. But his boyish looks belie his talents both as a competitive poker player and a cutthroat real estate mogul in the making.

He’s played in the World Series of Poker, finishing as high as third place in 2016. Over the course of more than 15 tournaments he’s won north of $50,000.

Steven also competes in national tournaments of the popular board game Settlers of Catan. Judge Laster, noting that he and his wife can no longer play Catan together, was curious about the tournaments. Was there prize money involved, he asked.

“I wish,” Steven told him. “Unfortunately, you know, it’s a pride thing. There’s no real prize.”

Steven went to Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan and Vanderbilt University in Tennessee, where he earned a degree in political science in 2013. When he returned to New York he worked part-time at Solil for seven years. He also did a brief stint at Gary Barnett’s Extell Development, which has done a number of deals with Solil, before heading off to the University of Pennsylvania to get his MBA in real estate at Wharton.

At Solil he started out on property management, leasing and building violations, eventually moving up the chain to do development, acquisitions and Solil’s specialty: high-profile net lease transactions.

He worked closely with his father, who Steven said devoted his life and professional legacy to real estate.

“Almost all our calls touched on the family business,” he explained. “That was of the utmost importance to him, and, honestly, it was what we bonded over.”

Father and son talked a lot about how one day Steven and his sisters would take over Allan’s branch of the family company.

When Allan died, his estate included about $100 million in stocks and bonds, plus several homes and a coin collection worth several million dollars. The majority of assets were in the Goldman properties.

Steven needed to appraise those properties in order to pay the taxes on his father’s estate, but he said Jane stonewalled him and her delays caused the estate to suffer a loss. (This was in 2022 as the Fed began hiking interest rates, driving down the value of financial assets.)

When Allan was involved in the business, he was able to represent his side of the family’s interests when it came to working with Jane. Steven said the unworkable situation with his aunt left him no choice but to file his lawsuit.

“Jane, besides being outwardly hostile to myself and the beneficiaries and executors, has shown time and time again that the interests are not aligned,” he said. “I’m seeking to do what my father did — to protect the beneficiaries — in a way that Jane won’t.”

Gold name, green thumb

Amy eschewed the family business to follow a career in psychology, working with emotionally disturbed children and earning her PhD. But her first love was horticulture.

“If I had it to do over again, I’d do plant science,” she said.

Amy Goldman Fowler is a leading authority on heirloom fruits and vegetables and is, according to the president of the New York Botanical Garden, perhaps the world’s premier vegetable gardener.

She’s authored five books on gardening and has another three in the works.

“Most garden writers don’t grow their own things they feature in their books, but I grow everything from seed myself, evaluate, field notes, taste tests, do extensive photography before doing the research and writing,” she said proudly.

Each book takes about 10 years to complete (she works on some concurrently). Amy said her father gave her one of the greatest gifts she could receive: the time to pursue her interests.

She had a good relationship with Sol. In 1987 he asked her to be an executor of his estate, she said, but she deferred to her brother because of his business experience. She agreed to be a successor if and when one of the executors died.

“He trusted my judgment. And he had confidence in me,” she said. “And here I am today.”

Amy did work in the family business part-time when her father was alive and served as executive director of the Sol Goldman Charitable Trust. (She said Jane fired her from that position.)

She was supportive of her sister. When The Real Deal published an article in 2013 highlighting Jane’s role running the business, Amy emailed her: SO PROUD OF YOU.

“I told her I was proud of her, because finally some public recognition,” Amy explained.

She described Allan as her “adored older brother,” and the two talked regularly on the phone where he’d ask her opinion on business matters.

“It was a very warm, open relationship,” Amy said. “And I knew he was acting in a fiduciary capacity to safeguard the entire family’s interests.”

Several years ago the two had broached the subject of making a succession plan for the next generation. In 2018 Amy shared with Allan an email from her lawyer about the need to begin discussing who would manage the company when Jane and Allan were no longer able to.

The lawyer was working on a revised operating agreement for one of the entities that held the Goldman properties. The succession talk was a piece of unfinished business that got left out, but Amy thought it was important.

“What about the next generation?” she asked.

It just happened

On a spring day in early May, Jane, Steven and Amy faced each other in a Delaware courtroom filled with family and supporters.

They were there to settle the matter of SG Windsor, a holding company buried deep within the company org chart that’s unremarkable except for the fact that it owns a 50 percent stake in Solil Management. The four Goldman branches each own a 25 percent stake in the LLC, though they knew little about what it actually did — or for some that it even existed — prior to the litigation.

When asked what, if anything, she does on behalf of SG Windsor, Jane quipped: “I go to court in Delaware.”

The holding company acts as a pass-through between Solil and the family. It does two things: distributes payments and files taxes.

The thing about SG Windsor, though, is that no one can really say how it came to be.

It was created shortly before Lillian died in 2002, but there’s no operating agreement saying who should manage it. (There was supposedly a draft operating agreement drawn up at the time, but it was never executed.)

There are no member certificates, nor any kind of paperwork admitting the siblings as members. Only the K-1 tax forms that the Goldmans receive each year prove they’re members.

“There are no documents establishing the transfer of interests in SG Windsor to the siblings,” Judge Laster wrote following the trial. “No one remembers how that was accomplished. It just happened.”

A white-bearded former corporate litigator, Laster has a habit of making himself the most memorable part of the cases he oversees. He’s built a reputation for being quick to call B.S. when he thinks someone in his courtroom gets out of line, whether that means firing lawyers he felt brought flimsy cases or rejecting settlements that didn’t pass muster. Critics say he sometimes overreaches.

Certainly the Goldmans know what an operating agreement is for and how to write one — they’ve done it for plenty of other entities — but for whatever reason they didn’t create one for SG Windsor.

Delaware’s LLC law says that in the absence of an instrument naming a manager, they default to being member-managed entities. For SG Windsor, all the siblings would then be managers unless Jane could prove that they had appointed her to run it via something like a vote or a verbal agreement.

“That’s not how our office operated,” she said when asked if such a vote ever occurred. “We’ve never raised hands and voted in that manner.”

“I don’t like his ethics. He would not be a good partner for me. It just would not work.”

Her argument is that she’s the manager of SG Windsor the same way she’s the head of the company overall: She’d been doing it all these years and no one ever objected.

Laster didn’t buy that and ruled that the law says what it says: SG Windsor is managed by its members. That was a win for Steven and Amy.

Next, Steven argued that since he’s in charge of his father’s estate, he should take Allan’s place as an SG Windsor member. The judge ruled that Steven is technically an “assignee” and doesn’t have a member’s management rights — a win for Jane.

But Laster did say that Steven could exercise certain membership rights in a few narrow circumstances when it comes to settling his father’s estate and administering his properties. That one’s trickier to call.

Steven’s legal team said the ruling gives him access to key company information that, among other things, helps strengthen their case in New York.

“If you want to manage the Goldman family real estate properties, you have to go through Solil, which means you have to go through SG Windsor,” his lawyer said. “SG Windsor is at the apex; it’s the key entity, and that’s why we’re here.”

Jane’s side downplayed the significance of the ruling, pointing out that Steven’s limited rights are temporary. Her lawyers also believe Steven and Amy have overstated the LLC’s significance. They say that while it’s true that it owns half of Solil, that doesn’t mean it manages it.

Jane’s lawyers say that Steven and Amy’s real end game is to deadlock Solil by preventing SG Windsor from attending any meeting of the members where the LLC would cast a vote.

“What they said was … ‘we can prevent it from showing up to a meeting so that there won’t be a quorum to function,’” Jane’s attorney said.

That will be hashed out in a Manhattan courtroom — what Laster refers to as “the big party up in New York.”

The Goldman “we”

A two-and-a-half-hour drive up I-95, the New York case revolves around the appraisal valuing the family’s put options. Steven and Amy accused Jane of handpicking Newmark from a list of appraisers because she knew she could put her thumb on the scale to influence its findings.

Jane denies this.

“We solicited bids from all of them, and we chose the one who was the least expensive,” she said during her Delaware testimony. “I thought somebody should thank me for choosing the least expensive one.”

“‘We’ in that is you, Jane?” Steven and Amy’s attorney interrogated.

“‘We?’ No. The Goldman ‘we.’”

“Here’s the question. You controlled the information that went to the appraisers?”

“I had not one bit of control over what went to the appraisers.”

“Nothing further.”

“I had a Chinese wall, which you will see.”

There’s something telling in Jane’s use of the royal we that goes to the core of the family’s feud.

Sol made Jane the executor of his estate, and over the course of nearly 40 years she’s interpreted that to mean manager of the entire Goldman family real estate business. (“A description so amorphous it purportedly includes entities not yet in existence,” is how Steven and Amy’s lawyers described it.)

That’s clearly not the case, though, as facts have shown there are important entities within the Goldman empire where Jane shares management with her siblings.

Jane spent decades carrying out the family legacy and providing for the Goldmans, with the understanding that they supported her role as leader. The last thing she expected was that one day someone would accuse her of illegitimately grabbing that power because she didn’t go around all day asking her brother and sisters to sign legal agreements.

The truth is, the Goldmans play fast and loose when it comes to defining some key parts of the business. They use terms like manager, administer, executor and owner interchangeably — and struggle to articulate the difference when pressed. They mistake “manager” in the everyday usage of the word for “Manager” in the strictest legal sense.

But in the bigger picture, the hostilities cut a lot deeper for a family that prizes its privacy and reputation. Parts of the Delaware and New York cases are marked confidential and put under seal to protect sensitive information. Still, there’s plenty of dirty laundry airing out.

The discovery phase in Delaware turned up an email Amy had received from her husband complaining about Jane’s management of the business. “Jane works for you and the other siblings,” he wrote.

This was the first time Jane had seen the email, and she was deeply hurt by it.

“I mean, I work there because this is what I was entrusted to do, and I think I’ve done it incredibly well. And I think my father would be proud of me, and I think my mother would be proud of me,” she said at the trial. “And to be talked [about] behind my back like this is insulting.”

When asked about it on the stand, Amy said she doesn’t see her sister that way.

“Look, this is something my husband said to me in a private conversation. This is immaterial. I just told you, I don’t see it as working for me. She has a responsibility, a duty of care and a duty of loyalty to the family. And she’s doing work she loves, too.”

Steven lamented that the whole affair may damage the Goldman reputation in ways that are impossible to repair.

“These are not scars that will vanish easily,” he said.