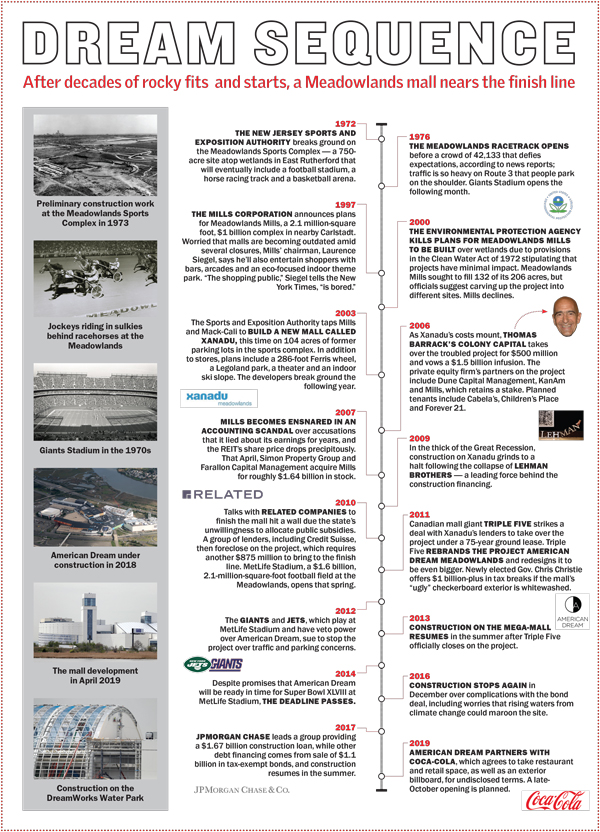

Life, liberty and the pursuit of shopping. So goes the American Dream — the mall-slash-amusement park in New Jersey’s Meadowlands that has weathered three developers, two designs and one calamitous recession.

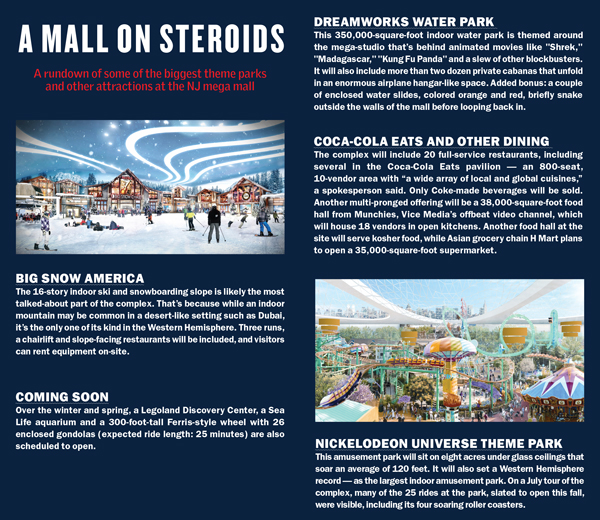

Indeed, the first phase of the $5 billion, 3 million-square-foot complex is finally poised to open in late October with a portion of the shops and restaurants launching alongside several nonshopping attractions, including an indoor ski slope dubbed Big Snow America, according to the project’s developer, Triple Five Group, which is based in Canada.

But there are some serious questions about whether American Dream, which was first conceived of nearly two decades ago when the retail landscape was healthier, can succeed.

For starters, it’s opening at a time when brick-and-mortar retail is facing an existential crisis fueled by the rise of online shopping.

And the way some of the mall’s development cost has been financed, which has essentially diverted property and sales tax money to pay off municipal bonds that back American Dream, has bothered critics who would have preferred the public money be spent on schools.

In addition, some are concerned about the location of the project — which sits just off the New Jersey Turnpike in the shadow of the MetLife football stadium. Roads are already too busy in that area, they say, and boosting public transit options would siphon critical taxpayer dollars.

Delays have also plagued the project, which former Gov. Chris Christie referred to as an eyesore and which was sued by the New York Giants and the New York Jets to stop construction. Numerous deadlines have come and gone, like the one that had the mall opening in time for the 2014 Super Bowl.

“It has been a bad idea since day one,” said Jeff Tittel, the senior chapter director of the New Jersey Sierra Club, of a project he calls “American Scheme” for sucking valuable time, energy and money away from what he considers more worthwhile public investments.

So the fact that American Dream is nearing the finish line after so many ups and downs, near-deaths and 11th-hour saves is a feat in itself, officials, developers and brokers said.

“It’s a huge gamble,” said Marcus & Millichap Senior Vice President Joseph French Jr., a mall specialist who’s predicted that 1,000 of the country’s 1,300 shopping malls will close in the next 20 years.

“But in concept,” French said, “I’m not willing to bet against it.”

That’s largely because the complex is something of an extreme test case, bordering on a last-ditch effort, for the American mall — one that hopes to lure in visitors with dining and over-the-top entertainment first and foremost, and then keep them there long enough that they will also get around to shopping afterwards.

The complex has partnerships with fast-growing media companies including DreamWorks, Coca-Cola, Nickelodeon, Lego and Vice Media. And in addition to the ski slope, it will include water and amusement parks, a skating rink and other flashy attractions.

The complex has partnerships with fast-growing media companies including DreamWorks, Coca-Cola, Nickelodeon, Lego and Vice Media. And in addition to the ski slope, it will include water and amusement parks, a skating rink and other flashy attractions.

In total, 45 percent of the 3 million square feet will be devoted to retail, with 55 percent earmarked for entertainment. That ratio, French said, is a smart update to the old mall paradigm and could be the key to the project’s success.

Go big or go home

Looming over the turnpike on 130 acres of state land, according to the state authority that operates the property, American Dream is clearly banking on its sheer size and its high-profile partnerships to turn itself into a destination.

It will include a DreamWorks movie-themed water park, a Nickelodeon Universe amusement park, a Legoland Discovery Center, an aquarium, a Ferris-style wheel and a sprawling food hall with an 800-seat area called Coca-Cola Eats.

That’s all in addition to the regular retail — 350 stores with a mix of national brands and pop-ups filling 1.5 million square feet. Those shops will inhabit more traditional real estate: long halls punctuated by atriums, though a giant tree-shaped sculpture from Burning Man — illuminated with 75,000 LEDs and playing music — will also be on display in a seeming bid for the hipster crowd.

As of early August, 85 percent of the retail space was leased, according to Triple Five, a private, family-owned company that has stakes in several other industries, including oil and gas and tech startups. Saks Fifth Avenue will occupy a two-level, 120,000-square-foot space; the posh retailer’s annual rent is $2.1 million, or about $18 a square foot, according to a 2017 appraisal of the property by CBRE.

Other tenants include Tiffany & Company, Hermès and Dolce & Gabbana, all of which will be housed in a luxury wing. Victoria’s Secret, Uniqlo and Sephora will also have outposts at the mall, which has annual asking rents of $100 to $500 a square foot, said Don Ghermezian, Triple Five’s CEO, who added that concessions such as improvement allowances have not been granted.

Saks’ rent is significantly lower because it’s the mall’s anchor tenant, according to a Triple Five spokeswoman.

But commercial brokers say the other rents seem very steep. By comparison, Roosevelt Field — the upscale Long Island mall anchored by Nordstrom, Neiman Marcus and Bloomingdale’s — commands about $50 to $200 a square foot, French said.

At American Dream, the higher asking rents have not hindered lease negotiations, according to Ghermezian. Some tenants have even expanded their planned footprints, he said. Lululemon Athletica, for example, opted to take 12,000 square feet, up from 4,600. And Barneys New York is still scheduled to open, even after the company declared bankruptcy this summer.

But that’s not to say the megamall is immune from today’s harsh retail realities.

Toys “R” Us — which filed for bankruptcy in 2017 and later liquidated its stores — was an original anchor tenant.

Similarly, Cirque du Soleil was supposed to have a permanent home in the complex, according to early reports, but that no longer seems to be the case. In August, a Cirque du Soleil spokesperson, somewhat cryptically, called the earlier reports “rumor.”

Construction on the American Dream site first began in 2004

Scattered amongst the brand-name retailers will be pop-up shops that will feature locally based startups with leases of less than six months, said Ken Downing, the chief creative officer, who joined Triple Five last spring after a 28-year run at Neiman Marcus.

Triple Five owns two other major malls — the 5.3 million-square-foot West Edmonton Mall in Alberta, Canada, and the 4.2 million-square-foot Mall of America near Minneapolis. Both of those gigantic properties are 95 percent occupied, Ghermezian said.

And the developer isn’t the only one still betting on the mall model.

Brookfield Properties is opening SoNo Collection, a 700,000-square-foot mall in Norwalk, Connecticut, that will have a Nordstrom, Apple store and Bloomingdale’s, according to news reports. Like American Dream, SoNo will also have pop-up shops.

The dominant trend in the region has been for shopping centers to reinvent themselves to avoid collapse.

Taking the space of a former Saks store at the Mall at Short Hills, a 1.4 million-square-foot property owned by Taubman Properties about 20 miles from American Dream, is an Industrious co-working facility, for example.

Likewise, at the nearby Westfield Garden State Plaza, which in 1957 was the first suburban mall in New Jersey, a J.C. Penney that closed in 2018 will be razed to make way for dozens of smaller shops, according to news reports. More strikingly, European owner Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield plans to add apartments and greenery on parking lots there. A call left with the mall’s managers was not returned.

Ghermezian said the pop-up stores at American Dream are not fillers for empty storefronts, as is often the case with vacant shops in New York. “We are not doing it to make storefronts look full,” he said.

As for the conventional tenants, leases stipulate that they need to embrace “experiential retail” in their stores, which could take the form of Instagram-worthy backdrops.

“It’s not necessary to have the same stores as on Rodeo Drive or Madison Avenue,” said Downing. “Customers are looking for a store that has a little personality.”

Dreams vs. reality

Industry sources predict that the complex will see big crowds for its opening and that the rotating pop-ups will keep customers coming back.

But maintaining the 110,000-a-day visitor level that Triple Five is aiming for — largely on par with its Minnesota property — will be challenging, they added.

Others suggest the possibility of an unpleasant Catch-22.

“If they don’t meet those numbers, the mall becomes a giant white elephant, with serious implications for the site and the region,” said Tittel of the Sierra Club. “If they do hit it, it will be car-maggedon all the time.”

By comparison, Walt Disney World in Florida averages 142,000 visitors per day, according to 2017 figures. And all of New York City sees 178,000 visitors on a daily basis, according to 2018 data.

“I don’t think the 110,000 number is a make or break for the project,” said Alan Marcus, the founder of the Marcus Group, a public relations firm that represented American Dream till 2014.

Triple Five’s business plan, as spelled out in the 2017 CBRE appraisal, assumes $117 million a year in retail rents and $82 million a year in ticket sales from the amusement parks to start.

Keeping visitors on-site for six hours — another Triple Five goal — may also be tough. The national mall average is one hour, even if most malls don’t have wave pools and hockey rinks.

“Most people think it’s a reach,” said GFP Real Estate Chair Jeff Gural, who’s a managing partner in a group that operates the horse racing track within the Meadowlands Sports Complex. “But I think it’s a spectacular project and I wish them well,” Gural, who’s not involved with the American Dream project, added.

One of the biggest financial obstacles for the mega-mall is that it’s located in Bergen County, which bans shopping on Sundays under local “blue laws.” The exact toll of that restriction is tough to gauge, brokers say, and may be offset by the fact that New Jersey doesn’t charge sales tax on clothes, which has historically siphoned business away from New York. The restaurants, roller coasters and ski slope can remain open on Sundays.

How visitors will get to the East Rutherford site is another outstanding question.

American Dream, whose visitors are mostly expected to come by car, has 11,000 parking spaces and access to another 22,000 around MetLife Stadium, provided there’s no football game, concert or other event.

Concerns that the mall will cause traffic and congestion nightmares during home games has already led to one legal battle: The Jets and Giants — who had veto power over any expansion plans at the Meadowlands — sued Triple Five in 2012 to stop the project. (Triple Five counter-sued, saying the teams were hurting its ability to get loans. The two sides signed an undisclosed settlement in 2014.)

Public transportation could be just as problematic as driving.

New Jersey Transit has allocated $8 million to expand three bus lines to American Dream, which will have its own self-funded transit center. While Ghermezian said that would be ready in time for this fall’s opening, the existing train line — which is now only used for big events and football games — may not be enough.

Even though trains are now supposed to run hourly, that will require more conductors, which New Jersey Transit has in short supply, argued Janna Chernetz, deputy director of the transit advocacy group Tri-State Transportation Campaign. Bringing tens of thousands of visitors to the mall every day — plus the 17,000 people who are supposed to work there — will have negative effects far and wide, said Chernetz, who’s a “strong critic” of the project. She also questions how many shoppers, burdened with bags, will want to take mass transit home from the mall.

“But we are at the point where we have to make the project work,” Chernetz said, adding that Triple Five should pony up for any train expansions.

Others argue that putting the developer on the hook wouldn’t be fair, noting that the Giants and Jets have, for better or worse, never had to significantly chip in for infrastructure improvements.

“If the teams say jump, the state says, ‘How high?’” Marcus, the mall’s former spokesman, said.

Indeed, because of its job-creation function, he said, American Dream should get state support. “People love to be negative about projects,” Marcus added.

For its part, Triple Five seems to be pulling out all the stops to ensure that transportation is not a make-it-or-break it issue for the project.

It’s running private shuttle buses, which will pick up visitors at sites in Manhattan, at airports and at ferry stops on the Hudson River. Favored customers can also potentially book two Rolls-Royces, Ghermezian added. And there are three landing pads on American Dream’s roof for those with the means to helicopter in.

“Whatever we can do to get the New York customer as quickly and as easily as possible, we will do,” Ghermezian said.

Triple Five CEO Don Ghermezian

The survivor

If American Dream seems like the product of a different era, it’s understandable. It’s been on the drawing board for years.

In 2002, New Jersey’s Sports and Exposition Authority issued a request for proposals to develop parking lots next to the now-defunct arena known as the Izod Center.

The Mills Corporation, a mall developer that had kicked around proposals for other parts of the Meadowlands since the 1990s, teamed with the Mack-Cali Realty on a mall-and-entertainment complex to pitch its idea.

The complex was approved in 2003 and broke ground a year later. Several components of that original plan — it promised a Legoland attraction, a Ferris wheel and a ski slope — made it to the final blueprint.

But its façade, which had blue and green checkered patterns, like bathroom tile, and orange and brown stripes elsewhere, was widely panned.

As governor, Christie called it “the ugliest damn building in New Jersey and maybe America.”

By 2006, Mills was over budget and in need of funding. It turned to investors including Colony Capital, the private equity firm founded by Thomas J. Barrack Jr., a confidant of President Donald Trump who is currently under federal scrutiny about foreign influence (Barrack hasn’t been officially accused of wrongdoing). After Lehman Brothers collapsed in 2008, jeopardizing $500 million in construction financing, Colony also ran into trouble.

Talks with the Related Companies to join the project came to a dead end, and a group of lenders led by Credit Suisse eventually foreclosed on the $2 billion, nearly complete site.

In 2011, Triple Five — passed over in the initial RFP — stepped in to rescue the property. It soon whitewashed the façade and reimagined the project, keeping the ski slope in place but expanding the complex to 3 million square feet from 2.2 million.

The company’s founder, Jacob Ghermezian, emigrated from Iran to New York in the 1940s and worked as a Persian rug dealer for more than a decade before relocating to Canada and expanding into real estate in the 1960s. The family made timely bets on housing and hotels in Edmonton during the area’s 1970s oil boom and later began to diversify.

Triple Five’s holdings in New York today include the Community Federal Savings Bank in Woodhaven, Queens, according to bond sale records.

The price of dreaming

Triple Five has a 75-year, $160 million lease for its site, though previous developer Mills prepaid the ground rent through 2024.

Triple Five has also benefited from major subsidies for the project, even if some of those tax breaks and credits are tools commonly deployed with economic development.

The first phase of the $5 billion complex is finally poised to open in late October, but critics say it’s out of touch with the way consumers shop today.

Rather than full property taxes, American Dream is responsible for so-called payments in lieu of taxes. In a complicated financing arrangement, those PILOTs will both flow to East Rutherford and help pay off $1.1 billion in tax-exempt municipal revenue bonds sold in 2017 to support the project.

New Jersey also waived sales tax requirements for the project, with that anticipated revenue also backing the unrated bonds, whose lead underwriter was Goldman Sachs.

The bonds are structured to pose no downside for taxpayers, as bondholders assume all the risk, according to Ghermezian. The high-yield bonds, which mature in 2056, were overperforming a year after being issued, according to news reports.

“There is zero risk whatsoever [to taxpayers],” said Ghermezian, who added that his family’s equity stake is about $650 million, or about 13 percent of the development’s total value.

Triple Five is no stranger to asking taxpayers to help foot the bills. In the mid-1990s, the company was planning on building a mall in Silver Spring, Maryland, also named American Dream. But the $585 million project ultimately collapsed because Triple Five was demanding too much of a subsidy from the public, up to $300 million, officials said at the time.

Meanwhile, the New Jersey mega-mall’s $1.7 billion in private construction financing, from a group of lenders led by JPMorgan Chase, comes due in 2021. To secure that loan, Triple Five had to put up a 49 percent stake in its Mall of America for collateral, meaning the Midwestern property could potentially get a new minority owner if American Dream imploded.

But Triple Five’s spokesperson noted that “such recourse is normal for construction financing.” The risk from such recourse is modest “with American Dream opening in just weeks,” she wrote in an email.

Key to the Meadowlands project, analysts say, was the deal with Coke, announced in June. They say it represents a unique effort at branding a mall in the manner of a sports arena. The 10-year multimillion-dollar agreement allows Coke to affix a large billboard on American Dream’s façade, at an as-yet-undetermined spot. (It should be noted that Pepsi sponsors MetLife Stadium, and its sign faces American Dream.)

Inside the mall, Coke will host events with athletes and other celebrities; the beverage giant will also have an interactive store with a podcast studio. Coca-Cola Eats, the massive food hall, will also be a branded feature with global cuisine and various Coke beverages.

“I think it was a real coup to get Coke,” Marcus said.

There have been smaller innovations as well. H Mart, the fast-growing Asian grocery chain, took 35,000 square feet, which will include a bar and a stage for small concerts. Putting grocery stores in malls — once a frowned-upon practice — is a necessary play today, said Chuck Lanyard, the president of Paramus-based retail brokerage the Goldstein Group, who represented H Mart in the lease deal.

“Malls all over the country are really in trouble,” Lanyard said. “Very wisely, it’s not just about retail but also entertainment.”

When American Dream opens on Oct. 25, critics will likely see an albatross of a project that is far removed from how consumers shop today — despite the bells and whistles. But others may appreciate the audacity of such a large mall-reinvention effort.

“If malls want to survive, they are going to have to do something like this,” Lanyard said. “But American Dream has gone many steps further.”