A short drive from downtown Miami, colorful murals highlight the Haitian diaspora and pink and yellow island-themed buildings dot Second Avenue in Little Haiti.

Among the traditional Creole eateries, some millennial-focused restaurants have emerged, advertising craft beer and featuring organic rotisserie chicken and jalapeno jam on their menus. The slow transformation has not gone unnoticed.

As some see the area poised to become the next Wynwood, Little Haiti has piqued developers’ interests in recent years.

But with an unemployment rate hovering at more than 20 percent — the city average stands at about 5 percent — developers have yet to begin building major ground-up projects in the neighborhood.

That could change, however, thanks to a little-known provision in President Trump’s tax plan that is designed to increase private investment in low-income communities nationwide.

Known as the Opportunity Zones program, it would provide tax incentives to developers who invest in historically distressed neighborhoods like Little Haiti, Little River and the city of North Miami, setting the stage for what could be massive redevelopment in those areas.

“There is a significant and potentially huge tax advantage to a developer building a project within these opportunity zones,” said Jon Chassen, a partner with the Miami law firm Bilzin Sumberg’s real estate and distressed property group.

Opportunities abound

Tucked away in the $1.5 trillion tax overhaul, the Opportunity Zones program was the brainchild of South Carolina Republican Sen. Tim Scott, meant to increase investment in low-income areas.

It works to incentivize investors by allowing them to defer their capital gains taxes — or taxes on gains made from the sale of certain types of assets — into Opportunity Zones funds. One Washington, D.C. nonprofit, the Economic Innovation Group, projects that U.S. investors have more than $2 trillion in unrealized capital gains just from stocks and mutual funds alone

For real estate developers and other investors, there are two major tax benefits from utilizing Opportunity Zones funds. The first is that the program allows investors to defer paying capital gains taxes until 2026, if they reinvest the gains in Opportunity Zones projects. The second is that investors can permanently forgo paying capital gains taxes on the sale or exchange of their investment in Opportunity Zones Funds, provided they hold the investment for at least 10 years.

According to the Economic Innovation Group, after 10 years an investor could see an added $44 for every $100 of capital gains reinvested into an Opportunity Zones program, compared to an equivalent investment in a traditional stock portfolio. That assumes the investment has annual appreciation of 7 percent.

“The real big incentive comes after 10 years. The kind of investments that are being held for 10 years are real estate investments,” said Brett Theodos, a principal research associate at the Urban Institute’s metropolitan housing and communities policy center.

There have been numerous past government efforts to encourage private investment in economically disadvantaged areas through tax incentives. What differentiates the Opportunity Zones program is that it encourages real estate construction or “substantial rehabilitation” of an existing property, some experts said.

“As a general rule, the intent is to spur new development,” Chassen said.

But it remains unclear which type of projects would benefit most from this tax break or whether existing projects might qualify. The U.S. Treasury Department is expected to release further guidance on the Opportunity Zones program in the coming months to provide more clarity.

So far, the law prohibits certain businesses from inclusion in the initiative such as private or commercial golf courses, massage parlors, along with suntan and gambling facilities.

State governors quickly nominated Opportunity Zones for Treasury Department approval. The zones are designed to be in areas that have a poverty rate of at least 20 percent or that has a median income that does not exceed more than 80 percent of the metro area. In total, there are 8,700 Opportunity Zones in the United States, both in rural areas and large metro areas.

“The challenge will be what products work best,” said John Balboni, a partner at Sullivan & Worcester, a Boston-based law firm that specializes in real estate and corporate practice. “Multifamily, warehouses, and self-storage will all take a look at this.”

While experts suggest that retail or multifamily may best fit these guidelines, some say that luxury condominiums would not be excluded from meeting the Opportunity Zones fund’s criteria. That raises questions about whether the program will really provide economic benefit to the region or would instead just be a boon to wealthy developers.

Adding to the capital stack

Shortly after the new law was announced, Avra Jain’s phone started ringing. The Miami developer, who made a name for herself redeveloping old motels on Biscayne Boulevard in the MiMo neighborhood, focuses on value-add projects in transitional neighborhoods such as Little River, Little Haiti and MiMo.

“When the law came out, the people who actually did read about it said Avra was on the top of the list to call,” Jain said. A former bond trader on Wall Street, Jain said that one of the biggest benefits of the program is that it could potentially allow her to access a new capital source.

Many banks have dialed back on their construction lending and other capital funding — such as the EB-5 visa program — has become more difficult to access because of regulatory restrictions. Now, developers, especially those with projects in low-income areas, may turn to Opportunity Zones funding to finance gaps in their project costs.

For developers like Jain, the new law could also mean that more banks and lenders are more willing to provide financing for projects in those low-income areas. “It makes what we do faster and easier,” she said.

South Florida zones

Florida has 427 designated Opportunity Zones in total that would qualify for the federal tax incentive program.

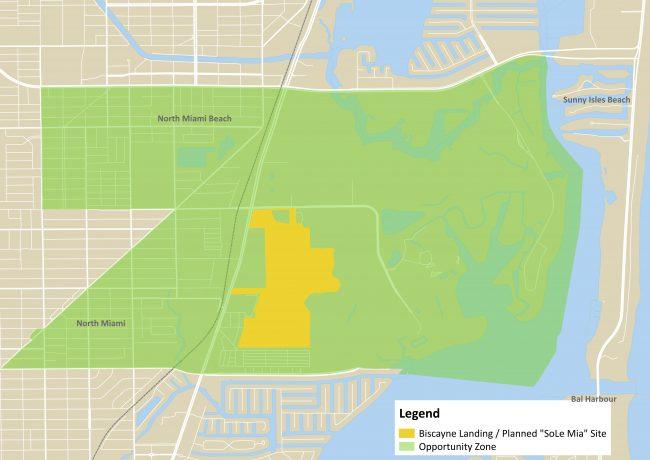

In South Florida, the Opportunity Zones map includes some in historically distressed areas such as Liberty City, Opa-Locka and Carol City. It also includes Little Haiti, North Miami and Aventura, where major mixed-use projects have already been proposed.

(Click to enlarge) Source: Map data provided by the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity and OpenStreetMap contributors. Maps and research by Haru Coryne.

“There was a lot of lobbying, some from the private sector and the public sector as to which ones could get the benefit,” said Andrej Micovic, an attorney with Bilzen Sumberg’s land development and government relations group.

In Little Haiti, Dragon Global’s Magic City Innovation District sits squarely in an Opportunity Zones tract on Second Avenue. The development firm, led by Tony Cho and Bob Zangrillo, is planning to build a $1.3 billion mixed-use entertainment center in Little Haiti that will have 20 buildings, including a 15,000-square-foot innovation center that will be home to startups. The project received initial financing from Arkansas-based Bank of the Ozarks in February, but has not broken ground. The project is expect to take 10 years to build.

Another project that could possibly qualify is SVP Realty’s plan to redevelop the nearby Design Place apartments at 5045 Northeast Second Avenue. It will be turned into a major mixed-use complex, with 2,798 residential units, 418 hotel rooms and 284,000 square feet of commercial and retail space.

Just north of Little Haiti, an Opportunity Zones tract encompasses the site of the $4 billion SoLe Mia mega-project at 15045 Biscayne Boulevard in North Miami. It received construction financing last year from Wells Fargo and the first phase of development is under construction. Most of the ground-up work, which will include a 10-acre lagoon with beaches, 12 residential buildings and 4,300 units — along with more than 1 million square feet of retail — has not begun.

Micovic said the question is, “If there are existing projects, are these laws going to allow for further investment in these Opportunity Zones buckets.” That remains unclear.

Economic impact

While the program would likely provide big benefits to developers already investing in these areas, some wonder whether the added tax advantages would be enough to justify new investment.

Jain, the Miami developer, said the program won’t alter where she is looking to build.

“I am not going to go buy a property just because it’s in an Opportunity Zone,” she said. “It doesn’t change my style.”

Darryl Jacobs, an attorney with the Chicago-based firm Ginsberg Jacobs, said he’s been fielding calls from property owners about the new zones, but added that it may take more than tax sweeteners for developers to start building.

“It’s going to make money less expensive for deals that are already happening in those areas, and I certainly think there will be some social impact investors coming into neighborhoods that could turn the corner soon,” Jacobs said. “But is a 10 percent or 15 percent avoidance worth it to take that risk? I just don’t know.”

The new program does makes real estate a more attractive investment option at a time of rising interest rates, according to Josh Migdal, a partner at the Miami law firm Mark, Migdal & Hayden.

“It’s a huge opportunity for development in certain pockets of Miami,” Migdal said. “It also allows investors to get a return that they otherwise wouldn’t be able to get, which will entice them to invest in real estate when we are near the end of the cycle.”

Neisen Kasdin, a managing partner at Akerman’s Miami office, adds the new program may further incentivize people to invest in areas that developers are already considering.

“That sweetens the investment,” he said. “That would be particularly the case for a project that doesn’t have an established market,” he added, “where investing there is riskier.”

Alex Nitkin contributed reporting