Being a developer can take a good amount of patience, but in Miami that virtue has long been put to the test.

Initial approval for a commercial or residential project can take between six months to a year. Physical plans are carried from one city department to the next, and any changes in an application can lead to more submissions and more delay. Once the initial step is secure, a developer usually can wait up to a year for a building permit.

Add on to that the roughly two years — on average — that it takes a project to be built, and it can take more than four years to complete a development.

“With the speed at which the market changes, that’s a really long timeframe,” said attorney Javier Aviñó, a partner at Bilzin Sumberg, and part of its land development and government relations practice.

“If you discourage developers from wanting to do projects in Miami, you’re really hurting your neighbors, the tax base, the new schools down the block,” added developer Avra Jain.

But Miami’s antiquated permit system just got a high-tech update, which city officials say will streamline the process and cut the wait time. Developers and other industry players remain wary, saying other problems persist.

Rolled out in December, the new permit system, Electronic Plan Review, recorded about 800 applications for new projects with the building department in the first month. Applicants can get feedback from city staff within two hours of submitting plans, compared to two weeks, the city said.

Multiple city departments can also review the same project simultaneously through Electronic Plan Review. Previously, a single set of plans would have to be walked to the different departments. Corrected plans can also be re-submitted electronically, another time-saver, the city says.

The system — by Arizona-based Avolve Software Corp. — has already been installed in smaller municipalities like Tamarac and Wellington. Avolve claims “100 cities, counties and states” use the system, according to its website.

Miami’s goal is not to speed up construction, but to reduce the turnaround time from when a developer or builder submits their application to when the developer receives a permit, according to the city’s building department director, Jose Camero.

Using the new technology, developer Melo Group got through its first round of reviews within six weeks — something Camero said would have taken “a good four to six months” before the city went digital.

Kemarr Brown — the city enterprise program manager who is in charge of implementing ePlan — said the focus now is training developers, contractors and owners on how to use ePlan and working out any kinks.

Overall, the city has spent roughly $7 million overhauling the building department, about $1 million of which went into a physical upgrade of its offices at the administrative building along the Miami River. The majority was spent on software and hardware, with funds also going toward IT consultants, professional services, licensing and permitting, and construction, Brown said.

The overhaul comes amid what a dozen developers, contractors, brokers and architects interviewed for this story agree remains a painstakingly slow permitting and approval process.

The data largely backs their claim.

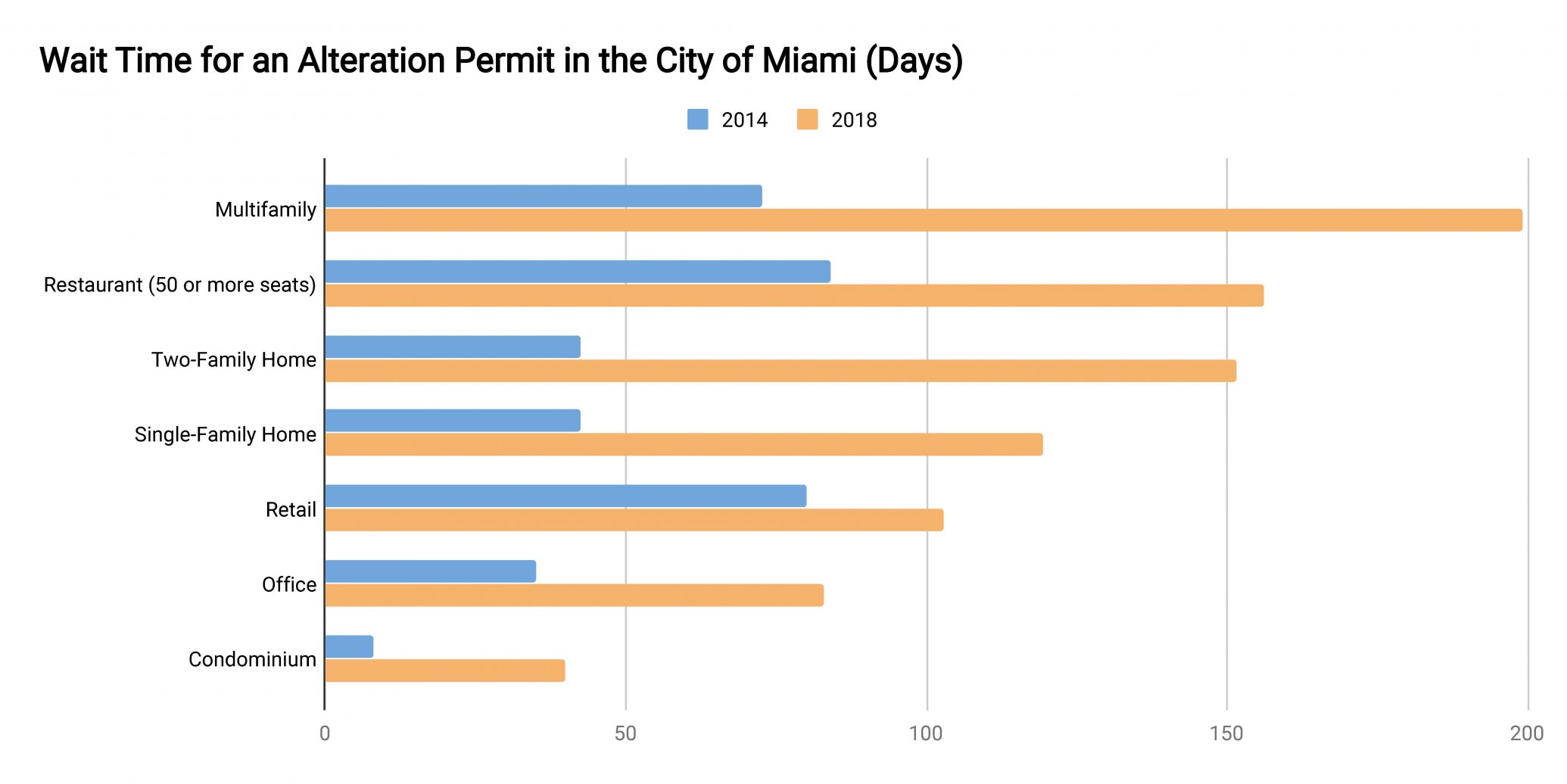

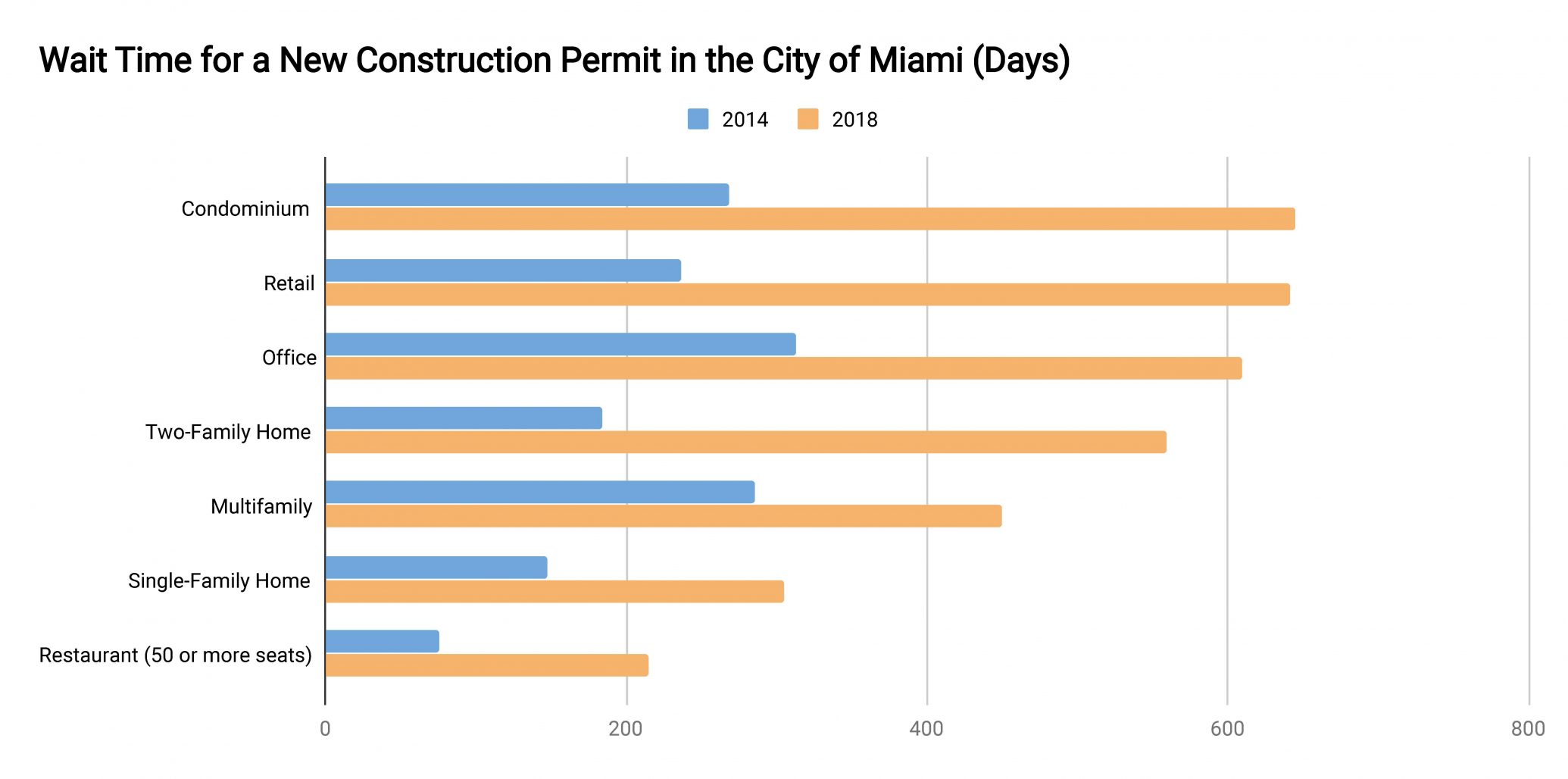

Between 2014 and 2018, wait time for permits rose dramatically in Miami in all categories, according to a Real Deal analysis of city data.

For alteration and remodeling permits, condo projects experienced the biggest increase in waiting times, from 8 days in 2014 to 40 days in 2018. For single-family homes, it went from 43 days to 119 days. For an office remodeling job, the wait went from 35 days to 83 days over the same period. Retail alterations permit wait times — not including restaurants — also rose, from 80 days in 2014 to 103 days in 2018.

As for new construction permits? That category also experienced a slowdown. It took developers a combined 2,164 days to get their permits for new construction in 2018. That’s double the number of days it took in 2014, according to TRD’s analysis.

The amount of time it took developers to secure the necessary permits for new condominium projects jumped to 645 days last year, from 268 days in 2014, according to TRD’s analysis. The data does not include larger, more complex projects that often go through a separate phased permitting process.

Most of the industry players who spoke for this story did so on condition their names be withheld for fear of antagonizing city officials. One such developer said permit applications often end up “languishing on people’s desks.”

And one attorney who works with developers added: “A small project — as small as a single-family home — can take just as long as a high-rise development and that is crazy.”

But improvements can also be seen.

In mid-December, Melo Group filed a building permit for a 1,042-unit apartment tower at 501 North Miami Avenue in downtown Miami. By the end of January, all of the necessary city departments had reviewed the 55-story project and provided comments. The Melo Group plans to break ground by 2020, but will likely get its building permit sooner, ahead of expectations.

Rendering of Melo Group’s Downtown 5th

Still, developers say the city has not addressed a glaring issue: staffing.

“At the end of the day, there have to be enough people to review the plans. There isn’t sufficient human capacity to accomodate the volume of work that is being put through,” Aviñó said. “The city needs to hire more people that have the skillset to be able to process these things effectively and efficiently.”

After the 2008 financial crisis, some municipalities in South Florida were forced to lay off employees, in some cases outsourcing their building department responsibilities. Over the past decade, those communities of Deerfield Beach, Weston, Pembroke Pines and Lauderdale-by-the-Sea hired private companies to run their inspection and permitting processes.

In the city of Miami, the building department had 61 employees in 2007. That shrunk to 55 by 2012 then rose to 91 as of this January, according to data provided by the city.

When the market peaks, “we try to bring in consultants to bridge the gap” and to avoid having to lay off employees, Camero said. “We had a substantial number of consultants in 2007.”

Around the same time, the city was also facing its share of financial issues. The city and its former budget director, Michael Boudreaux, were found guilty by the Securities and Exchange Commission of fraud. Boudreaux essentially “cooked the books,” orchestrating transfers of millions of dollars from the city’s capital improvement fund to its general fund to cover up budget deficits in the general fund, according to the SEC.

In 2010 and 2011, Miami was forced to lay off staff, just when construction cranes began popping back up. Development has boomed ever since, including massive projects like the $1 billion Brickell City Centre, along with condo towers like Aria on the Bay, Biscayne Beach, Echo Brickell, and 1010 Brickell, and many others.

Camero said the building department now has a number of open positions, including for building, plumbing and electrical inspectors, as well as supporting staff. For now, it is again using consultants, to help bridge that gap between ePlan and projects still using Miami’s old system.