Concern over climate change may be driving down sales volume and prices for homes along coastal Florida, according to a recently released report.

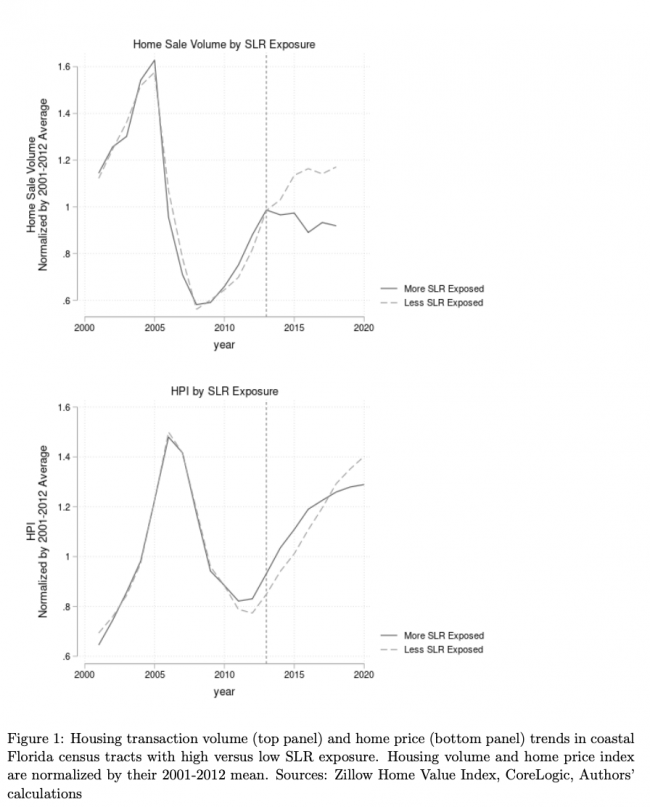

The study published by two researchers at The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania found that from 2013 to 2018, sales in coastal Florida census tracts with the most exposure to sea level rise declined between 15 percent and 20 percent, compared to tracts with low exposure. During the same period, sales volume in low risk areas rose, the study found.

Despite the relative drop in sales volume during that period, home prices in tracts highly exposed to sea level rise did not start to decline until 2016. By 2020, home prices in the high risk sea level rise tracts fell between 5 percent and 10 percent below where they would have if they were in low risk tracts.

The study doesn’t take into account the recent increase in high-priced waterfront home sales in pockets of South Florida, which brokers attribute to the pandemic.

Chart source: Benjamin J. Keys and Philip Mulder, The Wharton School at The University of Pennsylvania

The authors attribute the so-called “lead-lag” relationship between sales volume and home prices to a mismatch between sellers’ expectations and buyers’ appetites. Sellers overestimate what prospective buyers are willing to pay in coastal areas with high exposure to sea level rise, which drives down transaction volumes in those areas. Then, as “market optimists” gradually exit, home prices fall.

“The divergence between volume and prices can be explained by sellers in [sea level rise] exposed areas systematically underestimating the [sea level rise] risk discount demanded by increasingly anxious buyers,” the report said.

The authors’ chief explanation for the fall in sales and prices is climate pessimism. By matching county-level Yale Climate Opinions Survey data with sea level rise and sales data, the authors found that an additional 10 percent of residents worried about climate change in a county was associated with a decrease of 11 percentage points in home sales in high risk areas. For home prices, the relationship between climate pessimism was not significant until 2020, which suggests that climate change is increasingly figuring into prospective homebuyers’ decisions in high risk coastal areas, according to the report.

The authors also found that the divergence in sales volume and prices began in 2013 “as a confluence of events focused public attention on climate risk.” Hurricane Sandy struck the East Coast in October 2012, and within that year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued its worst-case global sea level rise projections.

The study ruled out tighter lending behavior as a cause for the declines in sales volume and prices in areas most exposed to sea level rise. The researchers found that both mortgage transactions and cash transactions declined by about 20 percent in highly exposed tracts by 2018. If lending explained most of the fall in transaction volume, mortgages transactions would have fallen at a faster clip than cash transactions.

Refinancing activity, loan denials and securitization also do not explain the fall in transaction volume, the study found. Refinancing activity did not fall in highly exposed tracts, and although loan denials did increase by 4 percent to 7 percent, the uptick was not enough to explain the 20 percent fall in sales with mortgages, according to the study. Lenders also have not securitized loans for homes in high-risk areas more often than they have for loans for homes in low-risk areas.

This study adds to the growing stack of evidence that climate change is transforming the residential real estate market on the coasts. Borrowers are increasingly signing mortgages that give them an out in the event of a flood or other climate-related events. Earlier reports have also found that lenders were tightening their credit standards and increasingly securitizing loans in areas with high flood risk, although this most recent study challenges those findings.

Last week, Tropical Storm Eta battered South Florida, flooding several major thoroughfares and knocking out power for tens of thousands of homes. On the commercial side, ratings agencies are increasingly including climate risk metrics in their ratings of commercial mortgage-backed securities.